- Scientific name: Glyptemys muhlenbergii

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Threatened (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Adult bog turtles from western Massachusetts.

The bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) is Massachusetts’ smallest and rarest turtle, found only in a few wetlands in western Massachusetts, and is one of the smallest turtles in the world. Adult bog turtles reach a maximum size of about 115 mm (4.5 in) in carapace length. The bog turtle’s carapace (upper shell) is oblong and can range in color from mahogany to dull brown. Some individuals have dark “starburst” patterns radiating from the growing center of each scute. Like other turtles in the Emydinae subfamily (like the wood turtle and Blanding’s turtle) the bog turtle’s plastron or lower shell is cream-colored with brown or black markings on each of 12 plastral scutes. Bog turtles have a distinctive, bright orange blotch on the side of their head, with a brownish or grayish neck and brownish limbs and tail. As with most emydine turtles, males have concave plastrons (females are flat to convex) and longer tales than females. Males are also larger than females. Young bog turtles look like miniature adults.

Similar species: Bog turtles are so rarely encountered by accident that they are seldom mistaken for any other species. However, other emydid turtle species are occasionally mistaken for a bog turtle—usually in areas well out of range. Perhaps most often, painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) are mistaken for bog turtles because they have a distinctive, yellow spot behind their eye. However, painted turtles have bright red on the limbs and around the margin of the carapace, as well as yellow stripes on the head and neck, and are found in deeper ponds and marshes than the fens frequented by bog turtles. Bog turtles could be confused with spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata), which are similar in size to the bog turtle and also found in fens and wet meadows in western Massachusetts. Spotted turtles typically have yellow spots on the carapace and are slightly larger and less oblong (but some individual spotted turtles are entirely spot-less). In addition, the spotted turtle lacks a prominent mid-line ridge (keel) on the carapace. However, the distinguishing keel can wear smooth in older bog turtles. Spotted turtles co-occurring with Massachusetts bog turtles are often stained with tannins or iron oxide and their spots may be indistinct.

Life cycle and behavior

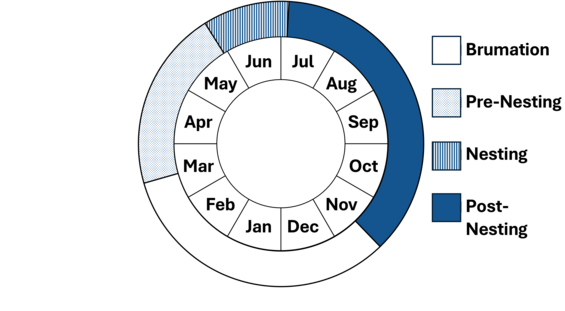

The secretive bog turtle overwinters (or “brumates”) from late-October to early April in underground, mucky seepages with a reliable source of groundwater. Some bog turtles may be active later in the fall, and earlier in the spring, in warm years. Bog turtles in New England occasionally overwinter communally, and some will overwinter with spotted turtles or even snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Bog turtles select overwintering sites with some woody structure, such as the root system of a tree or shrub.

Bog turtles are found primarily in very shallow and mucky wetland habitats. When they are disturbed or frightened, bog turtles will dig into the muck and disappear. Very rarely, bog turtles are in upland habitat adjacent to wetlands: they are primarily a species of shallow, palustrine wetlands and do not venture into dry uplands like their closest relative, the wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta). Most activity above ground occurs from April to October. A recent graduate study at UMass Amherst, which followed up on earlier graduate studies at the same site in the 2010s and 1990s, found that Massachusetts bog turtles have small home ranges, but that home range size can vary depending on habitat quality and the history of habitat management. At one study site, the average home range size of radio-tracked individuals remained stable over a multi-decadal study, while at another nearby site, home range size fluctuated in response to beaver flooding and habitat restoration activities.

Like many species in the subfamily Emydinae, bog turtles are opportunistic omnivores that consume both plant and animal material. The bog turtle’s diet consists of invertebrates including slugs, beetles, millipedes, insect larvae, and earthworms, and plants including pondweed (Potamogeton spp.), sedge seeds, and other material.

Bog turtles become mature around 10 years of age (perhaps later in Massachusetts). Mating typically occurs in spring and early summer—when turtles are most active. Gravid (or egg-bearing) females nest in the late afternoon or evening, depositing clutches of 2–5 white, elliptical eggs within the tops of vegetation hummocks. Like the spotted turtle and wood turtle, most nesting occurs in June. Bog turtle eggs incubate for 7–8 weeks and hatch in August or early September. Bog turtles can likely live 60 or more years; adults have been frequently found in the 2020s that were first marked in the mid-1980s. Recent graduate work at UMass Amherst reported high annual survival rates for adult bog turtles in western Massachusetts, suggesting that ongoing habitat management efforts are contributing to the long-term persistence of these critical populations.

Juvenile bog turtles also have a prominent orange patch on the side of their head, and look like miniature adults.

Distribution and abundance

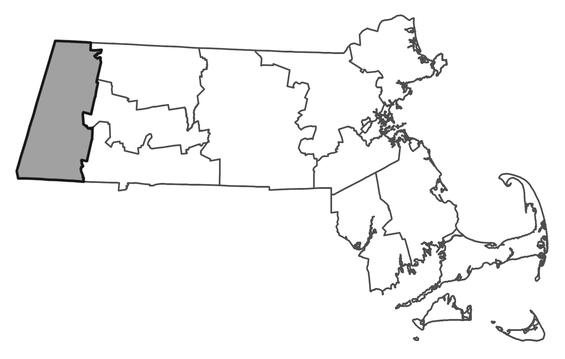

The bog turtle has a unique distribution that differs from other related turtle species. Today it occurs in two distinct and disjunct population segments: a northern and a southern population. Massachusetts represents the northeastern-most extent of the bog turtle's northern population, which extends south and west through western Connecticut, southeastern New York, New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, northern Delaware, and northern Maryland. The southern population is distributed in the Appalachian Mountains from southern Virginia to northern Georgia. There are a few isolated populations outside of these main ranges, including historic occurrences in the Lake George region, New York, and extant colonies in the Finger Lakes region of New York.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Bog turtles in Massachusetts are found only in low-lying, open-canopy, calcareous wetland—notably calcareous fens, shallow marshes, shrub swamps, and the margins of forested swamps. These fens are characterized by a mosaic of wetland plants, including many regionally rare species. Some dominant canopy species include tamarack (Larix laricina) and red maple (Acer rubrum). Common shrub associates include alders (Alnus spp.), willows (Salix spp.), poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), and shrubby cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa). Herbaceous associates include skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), marsh grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia palustris), goldenrods (Solidago spp.), and sedges (Carex spp.). Massachusetts bog turtles occur in small patches of open-canopy and shallow wetland habitat within dynamic wetland systems. These patches typically encompass early successional wet meadows and fen habitat, surrounded by advanced successional stages of freshwater marsh or wooded swamp.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

All evidence suggests that bog turtles are extremely range-restricted in Massachusetts and have likely been rare in recent decades. Bog turtles are known to have become locally extinct from at least one site in Massachusetts, and possibly two. Bog turtles are especially vulnerable to wetland habitat loss and degradation (including changes associated with hydrological alteration). Like other emydine turtles in Massachusetts, bog turtles mature late, have low nest survivorship, and lay relatively few eggs per year. These traits make them sensitive to even small increases in adult mortality.

Habitat-related threats to Massachusetts bog turtles include:

Habitat succession and invasive plants: The gradual succession of open-canopy fens to forested swamps reduces suitable habitat for bog turtles. Invasive plants, such as Phragmites, can outcompete native vegetation and alter the structure of bog turtle habitat.

Beaver (Castor canadensis) impoundment and hydrological alteration: Beaver activity can flood key overwintering areas, which can stress or displace or drown overwintering turtles. Also, beaver flooding can alter vegetation structure and habitat suitability by changing water depth. Similarly, hydrological alterations that influence the flow of water into or out of site can degrade wetland habitat quality for bog turtles. Filling and ditching wetlands was formerly a common practice in Massachusetts that likely eliminated or degraded historic bog turtle habitat.

Other significant threats include:

Collection for the pet trade: Illegal collection for the pet trade is a global threat to bog turtles. Because populations are typically very small, the removal of even a few adults can take decades to recover.

Mammalian depredation: Small mesocarnivores and predators such as weasels, minks, raccoons, skunks, and foxes prey on bog turtle eggs and juveniles.

Pathogens and disease: Several viruses and bacterial infections are known to pose an ongoing threat to bog turtle individuals.

Road mortality: Like all freshwater turtles, bog turtles vulnerable to being struck by cars whenever areas of suitable fen habitat are fragmented by roads. Even in unfragmented landscapes, dispersing individuals are killed on roadways.

Conservation and management

Fortunately, much of the known bog turtle habitat in the Commonwealth is conserved in perpetuity. However, as noted above, these core areas are influenced by land-use activities in surrounding parcels. Also, it is the case that adjacent parcels offer restoration opportunities (specifically, the chance to restore forest or farmland to open fen habitat). In these adjacent areas, habitat protection is still a top priority. Conserving the historic sites where bog turtles were known to occur between the 1960s–1980s is important, because these areas may have unique hydrological signatures that could support bog turtles in the future. Further, it’s important to note that while suitable habitat appears to be widespread in Berkshire County, no new populations have been discovered since the 1980s. Partners have conducted extensive surveys, including trapping and camera trapping, but have failed to detect new occurrences. Bog turtles in Massachusetts will benefit from the following management strategies:

Habitat management: Bog turtle habitat must be managed in accordance with federal habitat management guidelines (such as standing Biological Opinions) to create and maintain quality habitat for foraging, overwintering, and nesting. These activities should include:

- Controlling invasive species

- Managing vegetation succession to maintain (and expand) open-canopy conditions

- Maintaining and restoring appropriate hydrology

- Creating and/or protecting nesting and overwintering sites.

Landowner collaboration: While habitat management is usually most practical on state-owned conservation lands or protected reserves owned by NGOs, there are a few private landowners in a position to assist with expanded areas of habitat restoration and connectivity between subpopulations by partnering with MassWildlife to protect and restore habitat.

Promoting habitat connectivity: New roads near bog turtle fens should be restricted because of their potential to elevate mortality rates through roadkill, alter hydrology, and serve as vectors for invasive species. Existing roadways near occupied fens should be equipped with large (≥8’) structures designed specifically for wildlife passage at strategic sites (such as along brooks and at stream crossings) when they are proposed for resurfacing or reconstruction.

Disease surveillance: MassWildlife and partners should continue to conduct disease surveillance within occupied sites. Further research at the regional level is helpful to understand the threats posed by pathogens and disease to bog turtle populations.

Long-term monitoring: Continued low-intensity, long-term monitoring of bog turtle populations is important to assess the effectiveness of management actions and identify emerging threats. Studies like those by Sirois et al. (2014) and Vineyard et al. (2023) have provided valuable data on population trends and responses to habitat management.

Predator and collection prevention: To actively prevent the loss of individuals from illegal pet trade collection MassWildlife and partners will not disclose the location of these populations and take proactive steps to prevent unauthorized access. To reduce predation potential they will evaluate adjacent areas for features that could encourage increased population of mammalian predators and take corrective action if needed.

Acknowledgements

MassWildlife acknowledges the expertise of Angela Sirois-Pitel (The Nature Conservancy), who contributed substantially to the development of this fact sheet.

References

Conley, K.J., M.T. Jones, E. Crouch, S.L. Bartlett, A. Sirois-Pitel, D. McAloose, and M. Murray. 2024. Hepatic neoplasia in two Bog Turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) from the same Massachusetts fen. Northeastern Naturalist 31, Special Issue 12:G18–G27.

Erb, L. 2019. Bog Turtle conservation plan for the northern population. Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 89 pp.

Ernst, C. H., and J. E. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Second. Johns Hopkins University Press. 840 pp.

Klemens, M. 1987. Bog Turtle. In T.W. French and J. E. Cardoza (eds.). Endangered, Threatened and Special Concern Vertebrates of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA.

Klemens, M. 2001. Bog turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergii), Northern Population Recovery Plan. USFWS, Hadley, MA.

Macey, S.K., A.T. Myers, J. Tesauro, A. Feil, K. Polanco, J.A. Clark, and K.T. Shoemaker. 2024. Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) nesting ecology and the efficacy of predator excluders in New York. Northeastern Naturalist 31, Special Issue 12:G117–G137.

Myers, A. T., and J. P. Gibbs. 2013. Landscape-level factors influencing Bog Turtle persistence and distribution in southeastern New York State. Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 4:255–266.

Rosenbaum, P.A., J.M. Robertson, and K.R. Zamudio. 2007. Unexpectedly low genetic divergences among populations of the threatened Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii). Conservation Genetics 2007:331–342.

Shoemaker, K.T., and J.P. Gibbs. 2013. Genetic connectivity among populations of the threatened Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) and the need for a regional approach to turtle conservation. Copeia 2013:324–331.

Sirois, A. M. 2011. Effects of habitat alterations on Bog Turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii): A contrast of responses by two populations in Massachusetts, USA. Masters Thesis. State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry. 78 pp.

Sirois, A. M., J. P. Gibbs, A. L. Whitlock, and L. A. Erb. 2014. Effects of habitat alterations on Bog Turtles ( Glyptemys muhlenbergii ): A comparison of two populations. Journal of Herpetology 48:455–460.

Travis, K.B., I. Haeckel, G. Stevens, J. Tesauro, and E. Kiviat. 2018. Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) dispersal corridors and conservation in New York, USA. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 13:257–272.

Vineyard, J.A. 2023. Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) Population dynamics and response to habitat management in Massachusetts. Masters Thesis. University of Massachusetts; Amherst. 53 pp.

Whitlock, A. L. 2002. Ecology and status of the Bog Turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergii) in New England. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Contact

| Date published: | March 14, 2025 |

|---|