- Scientific name: Ribes lacustre (Pers.) Poir.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Bristly black currant (Ribes lacustre) is a low, bristly to spiny, straggling shrub measuring up to 1 m (3 ft) in height. Its leaves are alternate and are deeply cut with 3 to 5 lobes. Flowers are yellowish-green to pinkish, have fan-shaped to semicircular petal lobes, and are about 0.5 cm (less than 0.25 in) in diameter. It is a northern plant of cool, moist forest slopes, usually in dappled shade.

The bristly black currant is one of several members of the genus Ribes found in Massachusetts. A combination of characters must be used to distinguish it: 1) It has a “skunky” odor when the leaves, twigs, and fruits are crushed; 2) Its flowers and fruits are arranged in a raceme (which has a central stalk) which usually bears four or more flowers; 3) It has stipatate (stalked) glands on the ovaries of the flowers, and later on the (purple to black) fruits, giving them a “bristly” appearance; and 4) Its stems are armed with thin, bristly prickles, as its common name implies.

It can be difficult to distinguish between species in the genus Ribes in the vegetative state; flowers and fruits make identification much simpler. Swamp red currant (R. triste) co-occurs with the bristly black currant at a few streamside locations; however, it has smooth, red fruits and unarmed stems. Smooth gooseberry (R. hirtellum) is similar to bristly black currant; however, the broken twigs and fruit do not have a foul odor, the fruits are not bristly, and leaves are never as deeply cut as those of R. lacustre. Skunk currant (R. glandulosum) may grow in the same places as bristly black currant but has spineless stems. Wild gooseberry (Ribes cynosbati) may also be confused with bristly black currant. It can have stems with prickly or smooth internodes, and it has stipitate glands on its ovary/fruits, the petioles of the leaves have stipitate glands. The primary difference is the flowers and fruit of wild gooseberry are single or in 2 to 4 flowered corymbs, whereas the flowers of bristly black currant are in racemes of 5 -18 flowers.

Population status

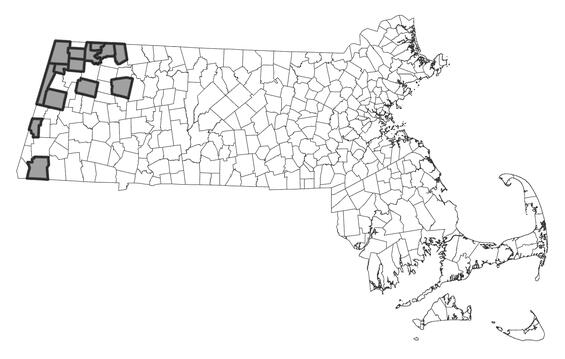

Bristly black currant is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as a species of special concern. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. It is rare here in the Commonwealth because it is a cool-climate plant with limited appropriate areas of moist, montane habitat. There are 22 current populations verified since 1999. All are concentrated in northwestern Massachusetts in Berkshire and Franklin Counties in areas of relatively high elevation or high latitude, or both.

Distribution and abundance

Bristly black currant is found across north North America from Newfoundland and Labrador to Alaska, south to New Jersey, West Virginia, South Dakota, Nevada and the mountains in California. In New England, it is thought to be possibly extirpated in Connecticut, vulnerable in Massachusetts, Secure in Vermont, and not ranked in Maine, New Hampshire or Rhode Island.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Bristly black currant is usually found in cool ravines and borders of swamps in upland regions of Massachusetts. It often occurs close to mountain streams, seepy ledges, or in steep rocky ravines, but it is also found in high-elevation swamps. The shrub prefers shaded to filtered light and wet soil, although one occurrence is in a mesic-dry region. It is found in association with northern hardwoods-hemlock forest. Surrounding vegetation may include yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), red spruce (Picea rubens), American mountain-ash (Sorbus americana), striped maple (Acer pensylanicum), and hobblebush (Viburnum lantanoides). Associated rare species are Braun’s holly fern (Polystichum braunii) and hemlock parsley (Conioselinum chinense).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Drastic alterations to the habitat supporting the bristly black currant could threaten populations. Large-scale logging, conversion of forest to developed land use, or alterations to stream or swamp hydrology could negatively impact habitat conditions for this species by altering its cool, moist, and shaded character. The invasive species multiflora rosa (Rosa multiflora) and barberry (Berberis spp.) have been documented at one station and may out-compete the bristly black currant. Direct impact to individual plants of bristly black currant could occur from off-trail hiker trampling or trail-widening activities. This species of cool habitats could be highly impacted by warming conditions expected with climate change (Staudinger et al. 2024).

Conservation

As with most rare plants, the exact needs for management of Bristly black currant are not known. The following advice comes from observations of the populations in Massachusetts. Excessive off-trail foot traffic on steep, unstable slopes may cause erosion or may damage populations through direct trampling; hikers should be strongly encouraged to stay on trails near populations of bristly black currant. Any future trail construction should take into account locations of this rare species to avoid direct impacts. Forestry activities should be avoided or very carefully planned and executed in areas near bristly black currant, since drastic canopy opening could alter the cool, moist nature of its habitat and open areas up to early successional competitors. Alterations to stream and swamp hydrology should be carefully avoided, since this species usually does not tolerate dry conditions. Stations for bristly black currant should be monitored for invasive exotic species such as barberry (Berberis spp.) which can also thrive in cool, moist forest conditions; if found, invasive species should be controlled.

References

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States

and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

Morin, Nancy R. Grossulariaceae in Flora of North America Vol. 8. Available on line at http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=20133 Accessed 5/27/2025.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 5/27/2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 5/27/2025.

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Contact

| Date published: | May 8, 2025 |

|---|