- Scientific name: Dichanthelium commonsianum (Ashe) Freckmann

- Synonym: Dichanthelium ovale ssp. pseudopubescens

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Photo by Bruce A. Sorrie

Commons’ rosette-grass (Dichanthelium commonsianum) is named for the botanist Albert Commons (1829-1919) who discovered this species. It is a short (15–60 cm [6–24 in]), hairy perennial in the grass family (Poaceae). It grows in small clumps and becomes more branched and bushy through the summer. Similar to other rosette grasses, Commons’ rosette-grass has an open, branched cluster of small spikelets, and each spikelet contains a single floret (a small individual flower). In Commons’ rosette-grass, the inflorescence is 3-10 cm (1.2–4 in) tall. The lower stems and leaf sheaths (the lower part of the leaf surrounding the stem) of Commons’ rosette-grass are hairy. The upper leaf blades are 2-6 mm (0.07-0.25 in) wide and somewhat hairy on both the upper and lower surfaces. Unlike some other rosette-grasses which creep and may root at nodes, Commons’ rosette-grass stems are erect or ascending.

To positively identify Commons’ rosette-grass and other species of Dichanthelium, a technical manual must be used. Commons’ rosette-grass is distinguished from other members of the genus in part by its distinct ligules of hairs that are 1-4 mm (0.03-0.15 in) long extending from the top of the leaf sheath. Commons’ rosette-grass is also characterized by its spikelets, which are 2.1-2.6 mm (0.08-0.1 in) long. Unlike some other species of rosette-grass, hairs on the vegetative structures of Commons’ rosette-grass do not have a pustule (small blister) at the base of each hair.

In Massachusetts, Commons’s rosette-grass must be distinguished from Dichanthelium villosissimum (Synonym D. ovale ssp. villosissimum), which has pustulose-based hairs on the leaf sheaths and larger leaves that are 6-10 mm (0.23-0.4 in) wide. Commons' rosette-grass can be distinguished from other common Dichanthelium species by the length of the spikelets. Both round-fruited rosette-grass (D. sphaerocarpon) and auburn rosette-grass (D. acuminatum) have smaller spikelets, while few-flowered rosette-grass (D. oligosanthes) has larger spikelets.

Photo by Arthur Haines, Native Plant Trust

Life cycle and behavior

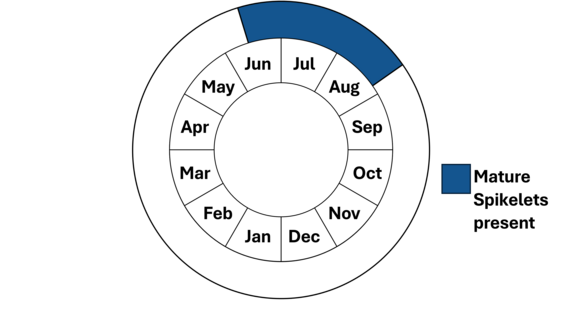

Commons’ rosette-grass produces terminal panicles in the spring (vernal phase) and lateral ones in the fall (autumnal phase) from the lower, mid or upper nodes. Most keys rely on the spring phase for identification, as the size of the florets can be slightly different. In Massachusetts, the spring phase for Common’ rosette-grass occurs from mid-June through July.

Research into the pollination of rosette-grasses has shown that this genus relies heavily on self-pollination through cleistogamous flowers (ones that do not open). A study of the related species D. clandestinum demonstrated that the cleistogamous flowers produce ten times more seed than the open flowers fertilized by wind pollination (chasmogamous). However, the seeds produced through wind cross-pollination had greater dormancy (Bell and Quinn 1985). The seeds of Commons’ rosette-grass are small and rounded, and no known seed distribution mechanism is known in this species. It is assumed that gravity plays an important role with seedlings growing near parent plants.

Population status

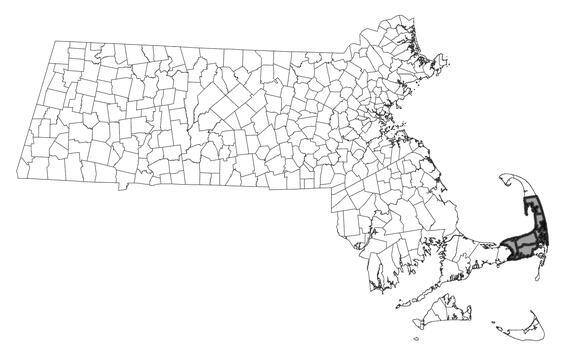

Commons’ rosette-grass is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as special concern. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale, and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. Since 1999, Commons’ rosette-grass has only been observed in 5 populations in Barnstable County. It was documented historically in an additional 17 locations including in Nantucket and Dukes Counties.

Distribution and abundance

Commons’ rosette-grass occurs on the coastal plain from Massachusetts south to Delaware, disjunct to Florida and west to Texas. It occurs locally at inland locations in Pennsylvania and Kansas, where it is considered critically imperiled. It also occurs in Indiana, Ohio, Arkansas, Missouri and Wisconsin. It is considered potentially extirpated in New York state and Ontario province.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Commons’ rosette-grass is typically found in dry, sandy habitat on the coastal plain and in sand barrens. It can also be found in openings in dry pine-oak woods in sites with moderate disturbance. Sandy areas along roadsides and power line cuts often provide the necessary ongoing disturbances needed to maintain habitat for Commons’ rosette-grass. Plants found in association with Commons’ rosette-grass include auburn rosette-grass (D. acuminatum), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and pitch pine (Pinus rigida). Early successional sandy habitats that are maintained by "natural" disturbance processes such as coastal winds or fire are likely to maintain long-term populations. At least one population occurs in the sandy soil surrounding a coastal plain pond along a trail that encircles the pond.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Photo by Bruce A. Sorrie

Threats

Specific threats to Commons’ rosette-grass include habitat loss to development and forest succession. Fire suppression may be negatively impacting this species. In addition, heavy recreational use in its habitat by off-road vehicles or hikers may destroy the populations. Although this species occurs exclusively on the coastal plain in Massachusetts, it is not under imminent threat due to rising sea levels.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Regular survey and monitoring are needed for this species to assess its rarity. The populations should be surveyed every 5 to 10 years and notes on the numbers and health of the plants are needed. The best time to survey is mid-July. The populations that have not been observed in the past 25 years should be surveyed for again.

Management needs

All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. Maintaining an open habitat for Commons’ rosette-grass may be necessary, which might include clearing of shrubs and trees. Protecting the open areas where the plants occur to prevent trampling and destruction by overuse through recreation may also be needed.

Research needs

While it is known that disturbance is needed, the extent is not known. It has been suggested that fire suppression might negatively impact Commons’ rosette-grass but no studies on fire effects were found. Additional research on the length that seed remains viable in the soil and grow when appropriate conditions return would be helpful. Finally, research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, this strategy could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Bell, Timothy J. and James A. Quinn. 1985. Relative importance of chasmogamously and cleistogamously derived seeds of Dichanthelium clandestinum (L.) Gould. Botanical Gazette 146(2): 252–258.

Dodds, Jill S. 2023. Dichanthelium cryptanthum Rare Plant Profile. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, State Parks, Forests & Historic Sites, State Forest Fire Service & Forestry, Office of Natural Lands Management, New Jersey Natural Heritage Program, Trenton, NJ. 15 pp.

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany, Eighth (Centennial) Edition—Illustrated. American Book Company, New York.

Freckman, R.W. and M.G. Lelong. Dichanthelium ovale. Flora of North America: North of Mexico, volume 25: Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Poaceae, Part 2. Oxford University Press, 2003. Pg 430.

Haines, Arthur. Flora Novae Angliae. New England Wild Flower Society, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. 2011.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 1/2/2025.

POWO (2025). "Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Retrieved 06 January 2025."

Sorrie, B.A. 1987. Notes on the rare flora of Massachusetts. Rhodora 89: 113-196.

Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the southeastern United States. University of North Carolina Herbarium, North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill, NC.

Contact

| Date published: | April 10, 2025 |

|---|