- Scientific name: Agkistrodon contortrix

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Massachusetts copperhead concealed in leaf litter.

The copperhead is one of Massachusetts’ most mysterious and rare snakes. Very few people will ever encounter a copperhead in Massachusetts by accident. However, several other harmless snake species, such as milk snakes and water snakes, are often mistaken for copperheads, so it’s important to bear in mind how rare they are.

Massachusetts copperheads have triangular, reddish-brown heads, and (like all snakes in the family Viperidae) vertical or cat-like pupils with a pale iris and dark pupil. Copperheads have striking, reddish crossbands against a beige or tan background. Neonatal and young copperheads are more grayish than adults, with yellow tail-tips. Adult copperheads are about 60–90 cm (24–36 inches) long, while neonatal or newborn snakes are 18–23 cm (7–9 inches). Males have longer tails than females but the two sexes can’t be told apart easily from a distance. Like the timber rattlesnake, copperheads have keeled scales.

Similar species: As noted above, copperheads are often confused with other snake species in Massachusetts.

Eastern milksnakes sometimes have distinctive reddish bands that are similar to the coloration found on a copperhead, but the markings form blotches rather than an hourglass shape and are against a lighter background. Milksnake’s pupils are round and not vertical. Milksnakes also have a black-and- white checkered pattern on their ventral surface. Milksnakes will “buzz” their tails in leaf litter when threatened.

Northern watersnakes can also have reddish tones, and distinctive reddish bands on their back, but have a narrow, dark-colored (not reddish-brown) head. Also, watersnakes are seldom found in upland, rocky, dry habitats where copperheads are most common.

Eastern hog-nosed snakes are sometimes brownish with reddish-orange tones, but they have a uniformly wide head with an upturned snout. Like milksnakes and watersnakes, they lack the hourglass pattern of a copperhead. Hog-nosed snakes are very rare in upland rocky habitats in Massachusetts, being more common in glacial outwash and sandy habitats.

North American racers are a glossy black color and have no coppery tones. Racers also have a whitish chin and smooth or “unkeeled” scales. Like the milk snake, racer will buzz its tail in leaf litter when startled.

Timber rattlesnakes are the only other pit viper in Massachusetts besides the copperhead. In some ways, they have a similar appearance to copperheads: they both have a stocky build with a triangular head and vertical or cat-like pupil. Some rattlesnakes can have mahogany or reddish bands or stripes. But rattlesnakes in Massachusetts are often either yellowish, grey, or brown with black, brown, or rust-colored blotches separated by crossbands rather than the hourglass pattern of the copperhead.

Adult copperhead showing reddish-orange coloration.

Life cycle and behavior

Massachusetts copperhead camouflaged in leaf litter.

Copperheads are cold-blooded or ectothermic, which means that individual snakes regulate their body temperature by changing their position in the environment. To warm up, copperheads bask in the sun, often concealed by leaf litter. When they become too hot, individual snakes will seek damp areas, cool crevices, shady understory areas, or below-ground shelter.

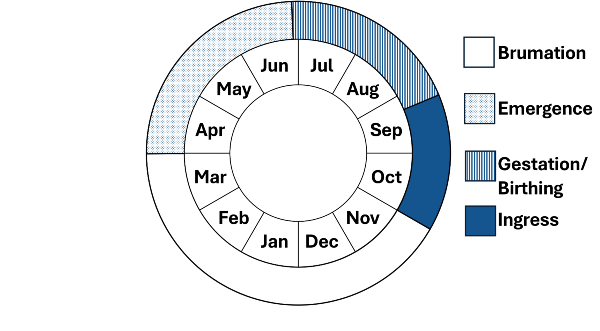

Like other vipers in the family Viperidae, copperheads have heat-sensing pits between their nostril and their eye, which detect infrared heat from warm-blooded prey like small birds and mammals. Copperheads also can perceive vibrations in the ground, aiding in both prey detection and predator avoidance. Like rattlesnakes and other vipers, copperheads have two hinged fangs in their upper jaw at the front of their mouth that inject venom. In Massachusetts, copperheads are generally active from April to October and they overwinter in rocky talus from November through March. However, they can emerge on warm days during the shoulder seasons.

In a typical year, copperheads emerge from hibernation by mid-April to bask on ledges and in sunlit areas of deciduous forest near their den site. Mating can occur in either spring or autumn. By late April or May in a typical year, copperheads disperse from the den area. Gravid females will often gestate their young in a sheltered, warm location that can be close to or more than a kilometer (0.6 mi) away from the winter den. Individual snakes return to their dens between early September and late October for brumation (overwintering).

Copperheads are ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young. Females give birth to 3–10 (typically 4–6) young in August or September. Copperheads reach sexual maturity at around five years old and have an estimated lifespan of more than 18 years. Juvenile copperheads eat insects (especially caterpillars) while adults mainly consume amphibians and small mammals. Adults will also eat small birds. Like rattlesnakes, copperheads are ambush predators, which means that they will lie in wait for prey.

Copperheads are generally not aggressive, and they typically avoid interactions with people. Like rattlesnakes and other snakes, copperheads will only strike if they feel threatened or cornered, especially if someone attempts to capture them. Copperheads are shy and reclusive, preferring to remain undisturbed.

Neonatal copperhead showing yellow tail and vertical pupil.

Distribution and abundance

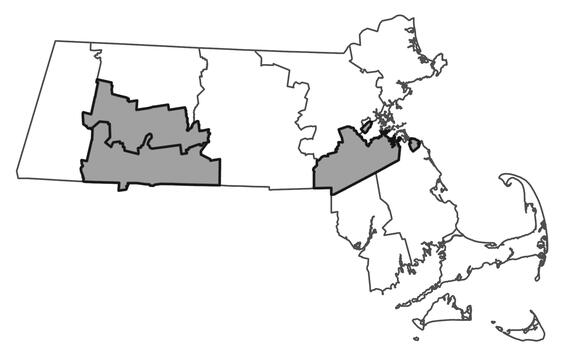

The copperhead is distributed from southern New England to Illinois, and south to Georgia. The copperhead is listed as an Endangered species in Massachusetts under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA) because of its rarity and declining populations. Copperheads are fully protected from harassment, collection, or killing under the MESA. Copperheads have only been documented in two general areas of Massachusetts: the southern Connecticut River Valley and the Boston area. All the known Massachusetts populations are small, highly isolated, and vulnerable to extirpation.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Copperheads in Massachusetts inhabit largely deciduous forests in mountainous areas. Massachusetts copperheads favor rocky terrain where bedrock is exposed at the surface (as opposed to areas of deep till or outwash). Some populations are associated with traprock (basalt) ledges with extensive rockslides and talus provide denning and basking sites, but populations are also known from areas of other intrusive volcanic rocks. Copperheads also utilize damp areas or wetland habitats. Copperheads select favorable microclimates within their rocky and mountainous habitats: south-, southeast-, and southwest-facing slopes offer basking opportunities in spring and fall. Copperheads also favor heterogeneous landscapes that include a mix of deciduous trees, Virginia creeper, poison ivy, lichens, damp leaf litter, red cedar, pine, hemlock stands, and grassy meadows are often found within copperhead areas. Further, copperhead habitat typically supports sufficient prey populations (small mammals, amphibians, insects). Copperheads overwinter in rocky subterranean dens in remote mountainous areas. These dens are often situated within talus. During the active season, copperheads utilize a variety of habitats, including basking sites that are open areas within rocky terrain, used for thermoregulation. Copperheads may be found near wetlands, wooded swamps, marshes, lakes, reservoirs, fields, meadows, wet woodlands, and quarries while hunting. Copperheads utilize similar rocky areas and varied forested landscapes as timber rattlesnakes.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Adult copperhead showing vertical pupil.

Massachusetts copperheads are threatened by several factors that make them vulnerable to population decline and extirpation, including habitat fragmentation, residential or industrial development of rocky and wooded habitat, roadkill on parkways and state highways, removal by collectors, and mortality at the hands of hikers and landowners. Key threats are as follows:

Habitat loss and fragmentation: Development of upland rocky areas for residential, municipal, or commercial projects, road expansion, and other land-use changes, degrades copperhead habitat and elevates adult mortality rates. Habitat fragmentation isolates populations, which increases their risk of collapse and extirpation. Anthropogenic changes to the copperhead’s environment, especially the introduction of invasive species, can affect copperhead populations. Invasive species can reduce habitat quality and alter prey availability.

Road mortality: Roads that bisect or fragment copperhead habitats pose a significant threat to all known Massachusetts populations. Copperheads of all ages are highly vulnerable to automobile strikes, especially during seasonal movements such as dispersal from dens and migrations to foraging or breeding areas.

Intentional killing and human disturbance: Copperheads are often killed by landowners when encountered in yards or by workers when found near utility installations. Also, recreational activity in copperhead habitats (such as hiking, biking, and off-road vehicle use) can disturb or kills snakes. Frequent disturbance can lead to stress, changes in behavior or movements, reduced reproductive success, and increased vulnerability to predators. Also: while public interest in copperheads is generally positive, the activities of some enthusiasts can inadvertently harm populations by creating new trails, disturbing den areas, and publicly sharing sensitive location information—all of which increase the risk of illegal collection or harassment.

Collection and the illegal reptile trade: Although illegal in Massachusetts and throughout the Northeast, collection of copperheads for the pet trade has affected Massachusetts populations. Removal from the wild reduces the pool of breeding individuals and results in a more vulnerable population.

Climate change: The potential impacts of climate change, such as elevated temperatures and altered precipitation patterns, will likely exacerbate known threats. Changes in local climate or precipitation may affect prey availability.

Conservation Action Plan

Adequately conserving copperheads at the few sites where they occur in Massachusetts will require the active participation of key landowners and a multi-lateral approach, including the following strategies:

Habitat protection: Although most known copperhead sites in Massachusetts are largely protected as conservation land, individual snakes move out from core areas and are frequently found on private or municipal land. It is important to strategically improve habitat connectivity between denning sites, including historic areas of occurrence, with surrounding habitats. Careful land-use planning and conservation will help to minimize habitat fragmentation and habitat degradation. Roads—especially those within protected areas such as State Parks and State Reservations—pose an ongoing risk to individual snakes. Measures designed to mitigate road mortality are important, such as wildlife passage structures and/or seasonal road closures

Public education: It is clearly important to improve public understanding of copperheads, which (along with timber rattlesnakes) are among the most misunderstood vertebrates in Massachusetts. Sustained and thoughtful education programs by MassWildlife, MassDCR, and other key partners can reduce misconceptions and misidentifications.

Minimizing human influence on montane habitats: Although controversial, it is important to limit new trail construction in copperhead habitat and to strategically retire existing trails. In some cases, it is appropriate to re-route or seasonally close existing trails that come close to dens or birthing areas.

Reducing negative interactions: Copperheads are sometimes killed by landowners, recreationists, and public safety officers (although any form of harassment is prohibited by state law). It is important to continue to enforce existing legal protections for copperheads. It is also important to minimize all forms of disturbance to sensitive habitat features, including frequent visits by curiosity-seekers, land managers, and even researchers.

Collaborative conservation: Realistically, copperhead conservation in Massachusetts will require collaboration among state agencies, such as MassWildlife, MassDCR and the Environmental Police, conservation organizations and universities, key municipalities, recreation groups, and the public.

References

Petersen, R.C., and R.W. Fritsch, II. 1986. Connecticut’s Venomous Snakes: The Timber Rattlesnake and Copperhead. Bulletin 111, State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut. Hartford, Connecticut: Department of Environmental Protection.

Smith, C. F., G. W. Schuett, R. L. Earley, and K. Schwenk. 2009. The spatial and reproductive ecology of the copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) at the northeastern extreme of its range. Herpetological Monographs 23:45–73.

Sutton, W.B., Y. Wang, C.J. Schweitzer, and C.J. McClure. 2017. Spatial ecology and multi-scale habitat selection of the Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) in a managed forest landscape. For. Ecol. Manag., 391 (2017), pp. 469-481.

Contact

| Date published: | March 14, 2025 |

|---|