- Scientific name: Terrapene carolina

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Adult eastern box turtle.

The eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) is Massachusetts’ only completely terrestrial turtle. It is a small species ranging from about 11.4-16.5 cm (4.5-6.6 in) in carapace length. The box turtle is named because it can completely close its hinged plastron (lower shell), protecting its head, limbs, and tail. Adult eastern box turtles have a circular to oval, domed shell with variable coloration, but usually some combination of yellow, orange, brown, or black. The carapace is usually brown or black with irregular yellow or orange blotches. The plastron typically is light-colored with dark variable patterns, but some may be completely tan, brown, or black. The head, neck, and legs also vary in color and markings but are generally dark with orange or yellow mottling. Eastern box turtles have a short tail and an upper jaw ending in a hooked or curved beak. Male box turtles often have red eyes, and females have brown or dark red eyes. Male eastern box turtles have a moderately concave plastron, while females' plastrons are flat to convex. Male box turtles also have longer claws on the hind feet, and longer and thicker tails than females. Hatchling box turtles have a brown or tan carapace with a light yellow spot on each scute (scale or plate) and a distinct, light-colored, mid-dorsal keel (ridge). Hatchling box turtles’ plastron is yellow with a black central blotch near the yolk scar, and no visible hinge.

Similar species

No other turtle in Massachusetts can close its plastron as firmly and completely as the eastern box turtle. Still, there are several related turtles that can be found in the same habitats, and some of them could be confused for eastern box turtle, especially if discovered dead on the road (as many are). Subadult Blanding's turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) could be mistaken for an eastern box turtle, because both have a moveable plastron. Blanding's turtle's plastron does not close as completely as the eastern box turtle's. Both species may have yellow markings on the carapace, but the markings on a Blanding's turtle are spots, flecks, or vermiculation rather than irregular or palmate blotches. Adult Blanding's turtles are much larger box turtles, ranging from 15-23 cm (6-9 in) in shell length. While both species may be found in similar terrestrial habitats, especially in Middlesex County, the Blanding's turtle is more strongly aquatic. Wood turtles (Glyptemys insculpta) are a semiterrestrial turtle species co-occurs with eastern box turtles in similar terrestrial habitats, especially in the southern Connecticut River Valley and in parts of Middlesex County. The wood turtle has a more flattened and more “sculptured” brown carapace. The wood turtle is also larger than the eastern box turtle, reaching up to about 20 cm (8 in) in shell length in Massachusetts. Spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata) could be mistaken for eastern box turtle, especially as hatchlings, as both have single, light-colored spots on each scute when born. However, the spotted turtle lacks a mid-dorsal keel and is darker than the box turtle. As an adult, the spotted turtle is smaller than the eastern box turtle, reaching a maximum size of only 12.7 cm (5 in). Some box turtles from the pet trade show up occasionally in Massachusetts, and could create some confusion. The Three-toed box turtle (Terrapene triunguis) is the most common of these. Three-toed box turtles are native to the Mississippi Valley, but historically appeared in the pet trade in New England and appear occasionally in the wild in Massachusetts. Three-toed box turtles generally have a uniform or horn-colored carapace and three toes on the hind foot.

Adult eastern box turtle.

Adult male eastern box turtle.

Adult female eastern box turtle.

Life cycle and behavior

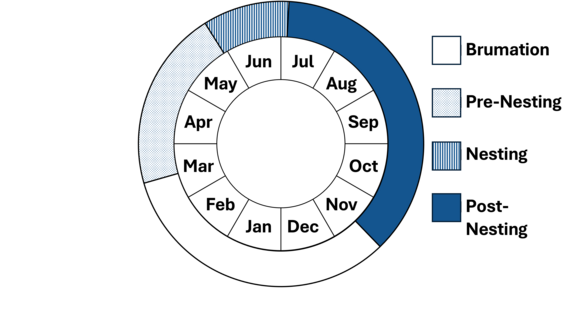

Like the four other emydine (subfamily Emydinae) turtle species in Massachusetts, eastern box turtles are long-lived, with individuals regularly reaching up to 50 years of age or more. Centenarians exceeding 100 years have been reported from the wild in Massachusetts and New York. Like most other non-marine turtles in Massachusetts, the eastern box turtle bromates (or overwinters) from late October or November until mid-March or April, depending on the location in the Commonwealth. Box turtles overwinter in upland forests and forested swamps, a few inches under the soil surface, covered by deciduous leaf litter. As temperatures drop and near the first severe frost, box turtles burrow into their overwintering position. Several individuals may overwinter in proximity to one another, but box turtles are generally not communal in the winter. Some individuals may emerge prematurely during warm spells in winter and early spring. During the spring, eastern box turtles start to forage and mate in forests and fields. In summer, adult eastern box turtles are most active in the morning and evening, particularly after rainfall. To avoid the heat of the day, they seek shelter under rotting logs or masses of decaying leaves, in mammal burrows, or in mud. Though they are the most terrestrial turtle in the northeastern United States, they readily enter shaded, shallow pools and puddles during heat waves and remain there for periods varying from a few hours to a few days. Eastern box turtles are omnivorous, feeding on land on slugs, insects, earthworms, snails, and carrion, as well as mushrooms, berries, fruits, and green shoots of young plants.

Females reach sexual maturity at approximately 10-13 years. Mating is opportunistic and may take place anytime during the active season. Courtship begins with the male circling, biting, and shoving the female. Females can store sperm and lay fertile eggs for several years after copulation. Massachusetts females nest from late May, throughout June, and into early July and can travel significant distances to find appropriate nesting habitat. They may travel up to 1.6 km (1 mi), crossing roads during their journey. Nesting areas may be in dry, well-drained, early successional fields, meadows, utility corridors, large woodland openings, roadsides, gardens, residential lawns, mulch piles, beach dunes, and abandoned gravel pits. Females sometimes exhibit nest site fidelity, laying eggs near the previous year's nest. Females typically start nesting in the late afternoon or early evening and continue for up to five hours.

Adult female eastern box turtle.

Distribution and abundance

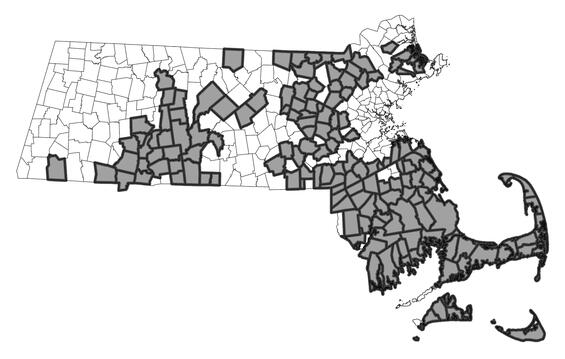

Eastern box turtles are distributed from extreme southeastern New Hampshire (and possibly southern Maine), south to northern Florida, and west to Michigan, Illinois, and Tennessee. Another species of forest-dwelling box turtle, the three-toed box turtle, resides in the Mississippi Valley. In Massachusetts, box turtles are more commonly encountered in the southeastern counties, and generally below 180-240 m (600-800 ft). Box turtles seem to be very rare in Essex County—a new discovery of a robust population there would be a significant find. The species is well-known to occur on Martha's Vineyard, but recent records from the Elizabeth Islands are sparse, probably because the islands are difficult to access and survey. Its current status on Nantucket is questionable. Box turtles were probably native to most of the larger islands in the Commonwealth. Records from Berkshire County are also sparse, and no populations are known. If box turtles occur naturally in Berkshire County, it is probably in the low hills near the Connecticut border in the Housatonic River valley.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Box turtles occur in a variety of upland habitats, but in Massachusetts they may be found in mesic woodlands, mixed pine-oak forest, pine barrens, old fields, brushy fields, scrub thickets, marsh edges and forested swamps, bogs, swales, fens, riparian areas, and well-drained bottomlands. They are found in and around the margins of xeric pine barrens, they are more common in adjacent habitats where they intersect with mesic hardwood stands. Box turtles rely heavily on early-successional clearings, abandoned gravel pits, powerline rights of way, and old fields, and they are most common in mosaics of mesic forest interspersed with early successional habitats and suitable nesting areas. Their search for early successional habitats also brings them into residential yards and neighborhoods.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Box Turtle habitats in Massachusetts.

Threats

Eastern box turtles occur in Massachusetts at the extreme northern edge of their large distribution. Here they face numerous threats, including land development and habitat fragmentation, road mortality, illegal collection, and diseases. Of these, habitat destruction and fragmentationare the most pressing concern: residential, commercial, and industrial development continues to reduce and fragment box turtle habitat. Habitat succession also presents a significant problem in some areas; the gradual conversion of open-canopy nesting areas to forest reduces overall habitat quality and results in longer-ranging animals. Further, invasive plants colonize new habitats following disturbance and can outcompete native vegetation and alter the structure of box turtle nesting areas. Predators such as raccoons, skunks, foxes, squirrels, and chipmunks can have a greater impact on turtle populations in suburban areas where they are human commensal species. Box turtles are vulnerable to being struck by vehicles when crossing roads. Illegal collection for the pet trade (and as personal pets) is a global threat to box turtles. Federal and state law enforcement are aware of recent cases of illegal trade in Massachusetts box turtles. Also, the release of non-native box turtles (such as the three-toed box turtle) may introduce new diseases and parasites, and result in hybridization with native eastern box turtles. Emerging diseases, such as ranavirus and Mycoplasma, pose ongoing threats to wild box turtle populations. Mowing fields and powerlines (and other similar habitats) during the active season (between April and October) can kill or injure box turtles that congregate in fields. ATVs can disturb or destroy box turtle nests and degrade nesting areas.

Conservation and management

The eastern box turtle is a species of special concern under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA), and MassWildlife’s conservation efforts focus primarily on protecting and managing their habitats. Important areas of habitat remain unprotected and need to be conserved. Habitat management should consider box turtles’ activity season and use machinery, mowers, and prescribed fire during the inactive season. Habitat management is most practical on state-owned conservation lands (i.e., DFW, DCR), but several NGO partners are working tireless to manage the state’s remaining wild areas.

Wildlife passage structures should be considered at strategic sites on existing roads where box turtles consistently appear on the roadway surface, especially in southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod, and the southern Connecticut River Valley. Appropriate wildlife corridor structures should be considered for major road projects within box turtle habitat. MassWildlife should continue to work with MassDOT and local/municipal public works departments to inform them where these measures would be most effective for box turtle conservation.

Educational materials have been developed (and should be distributed to the public) regarding the detrimental effects of keeping our native box turtles as pets (an illegal activity that slows reproduction in the population), releasing pet store turtles (which could spread disease), mowing fields and shrubby areas during the active season, feeding suburban wildlife (which increases numbers of natural predators on turtles), and driving ATVs in nesting areas (especially in June). People should be encouraged, when safe, to help box turtles cross roads (always in the direction the animal was heading). Box turtles should never be transported to "better" locations, as they will naturally want to return to their original location and likely need to traverse roads to do so.

A recurring, standardized monitoring program will provide valuable data on population dynamics, habitat use, and the effectiveness of conservation efforts. Community science (citizen science) efforts, such as those under way in West Virginia, can also be successful in gathering data and engaging the public in conservation. Further research on the impact of prescribed fire and habitat management on eastern box turtles is needed to inform best practices. Surveys in data-deficient areas, such as Essex County, most of Franklin County, and Berkshire County, would fill knowledge gaps and guide land conservation and habitat management efforts. Developing methods to minimize mower mortality in fields and power lines is crucial to reducing accidental deaths. Additionally, distinguishing viable populations from ghost populations is essential for prioritizing conservation efforts.

Acknowledgments

Lori Erb, Liz Willey, and Tom French contributed to earlier versions of this species account.

References

Babcock, H.L. 1971. Turtles of the Northeastern United States. New York: Dover Publications.

Buchanan, S.W.,T.K. Steeves, and N.E. Karraker. 2021. Mortality of eastern box turtles (Terrapene c. carolina) after a growing season prescribed fire. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 16(3):715–725.

Dodd, C.K. 2001. North American Box Turtles: A Natural History. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, USA.

Erb., L., L.L. Willey, L.M. Johnson, J.E. Hines, and R.P. Cook. 2015. Detecting long-term population trends for an elusive reptile species. Journal of Wildlife Management 79:1062–1071.

Ernst, C.H., J.E. Lovich, and R.W. Barbour. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London.

Gordon, A.B., Jr., D. Drummey, A. Tur, A.E. Curtis, J.C. McCumber, M.T. Jones, J.C. Andersen, and G.V. DiRenzo. 2024. The effect of myiasis on Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) body condition, movement, and habitat use at Camp Edwards in Massachusetts. Northeastern Naturalist 31, Special Issue 12:T55–T76.

Harris, K.A., J.D. Clark, R.D. Elmore, and C.A. Harper. 2020. Direct and indirect effects of fire on Eastern Box Turtles. Journal of Wildlife Management 84:1384–1395.

Lazell, J. 1974. Reptiles and Amphibians of Massachusetts. Lincoln, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Audubon Society.

Lazell, J. 1969. Nantucket Herpetology. Massachusetts Audubon 54 (2): 32–34.

Melvin, T.A., and G.J. Roloff. 2018. Reliability of postfire surveys for Eastern Box Turtles. Wildlife Society Bulletin 42:498–503.

Nichols, J. T. 1939. Data on size, growth and age in the box turtle, Terrapene carolina. Copeia 1939: 14–20.

Rimple, R.J., M.T. Kohl, K.A. Buhlmann, and T.D. Tuberville. 2024. Translocation of Long-term Captive Eastern Box Turtles and the Efficacy of Soft-release: Implications for Turtle Confiscations. Northeastern Naturalist 31, Special Issue 12:C17–C26.

Roe, J.H., K.H. Wild, and C.A. Hall. 2017. Thermal biology of Eastern Box Turtles in a Longleaf Pine system managed with prescribed fire. Journal of Thermal Biology 69:325–333.

van Dijk, P.P. 2011. Terrapene carolina. International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species. www.iucnredlist.org.

Walden, M., and N. Karraker. 2018. Hibernal phenology of the Eastern Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina carolina: William Floyd Estate, Fire Island National Seashore. Natural Resource Report NPS/NCBC/ NRR-2018/1595, U.S. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Willey, L.L. 2010. Spatial ecology of Eastern Box Turtles (Terrapene c. carolina) in central Massachusetts. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA. 200 p.

Contact

| Date published: | April 17, 2025 |

|---|