- Scientific name: Heterodon platirhinos

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Adult eastern hog-nosed snake from Cape Cod, Barnstable County, Massachusetts, showing upturned nose. Photo: Scott Buchanan

The eastern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon platirhinos) is a recent addition to the Massachusetts Endangered Species list: it was added as a Species of Special Concern in 2018 because of clear evidence of decline statewide, especially in the southern Connecticut River Valley. Hog-nosed snakes are thick-bodied, mid-sized snakes that have a wide head with a distinctly “upturned” or hog-like snout. Hog-nosed snakes sometimes bold color patterns, with light background colors of yellow, gray, or olive. While some individuals are melanistic (with a dark dorsal surface and light underside) most individuals are clearly patterned by a series of large, rectangular, dark spots along the back that alternate with dark spots on the snake’s sides. Hog-nosed snakes have keeled scales, so the skin appears rough and not glossy or smooth. The underside of their tail is lighter than the rest of the ventral surface or belly. Adults grow to about 50–70 cm (20–27 in). The hog-nosed snakes (Heterodon spp.) diverged from their closest living relative in Massachusetts (the common wormsnake, Carphophis amoenus), roughly 30 million years ago.

Similar species: Most of Massachusetts’s 14 snake species are frequently misidentified. The eastern hog-nosed snake is no exception. It can be easily mistaken for other native snake species because of its patterned appearance. Three species most likely to be mistaken for a hog-nosed snake, or vice-versa, include the following species that are all more commonly encountered in Massachusetts than the hog-nosed snake:

Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum): Both hog-nosed snake and milksnake typically have similar blotched patterns, the milksnake has a distinct black and white checkered pattern on its ventral underside or belly. Additionally, the milksnake lacks the upturned snout (its snout is softly rounded) and does not display the impressive defensive behaviors that are typical of the hog-nosed snake. Milksnakes are also found in a wider range of habitat conditions than the hog-nosed snake, which is generally found at low elevation near sandy outwash areas.

North American racer (Coluber constrictor): Juvenile North American racers are patterned and may be colored similarly to the hog-nosed snake. However, like milksnakes, racers lack the upturned snout. Racers also have smooth scales as opposed to the keeled scales of the eastern hog-nosed snake.

Northern watersnake (Nerodia sipedon): As the name implies, watersnakes are generally found in close association with wetlands and ponds. In contrast, hog-nosed snakes are typically found in xeric (dry) uplands and sandy areas of glacial outwash. Again, the watersnake lacks the upturned snout.

The hog-nosed snake also differs from other native, patterned snakes in its unique defensive behaviors. When threatened (or provoked) the hog-nosed snake flattens its neck and inflates its body, resembling a cobra. If further disturbed, or handled, some individuals will thrash around violently, roll onto their backs, regurgitate stomach contents and saliva, and “play dead”.

If captured, hog-nosed snakes will sometimes feign death, gape their mouth, and eject their stomach contents and saliva. An adult from Franklin County, Massachusetts is pictured.

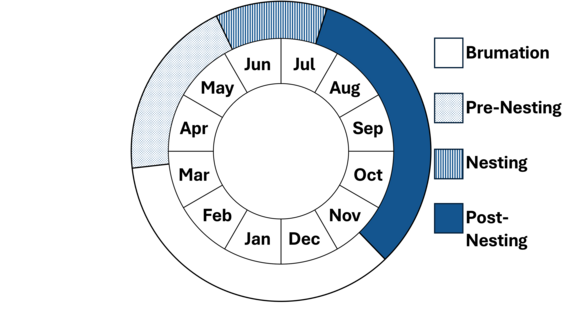

Life cycle and behavior

Eastern hog-nosed snakes have low annual survivorship rates, but higher fecundity compared to other native snake species of similar or larger size. This life history may allow hog-nosed snakes to maintain viable populations in areas defined by environmental stochasticity, such as interdunal habitats. Mating occurs in September on Cape Cod, and female snakes typically deposit 15–25 eggs (clutch size of 4–61 eggs have been reported) in sand, sandy loam, or mulch in June or early July. Eggs hatch between August and September. Eastern hog-nosed snakes are dietary specialists (they have been called an “extreme toad specialist”). Indeed, they feed primarily on toads and, to a lesser extent, other species of anurans (frogs). This specialized feeding habit likely leaves them vulnerable to localized amphibian declines.

Distribution and abundance

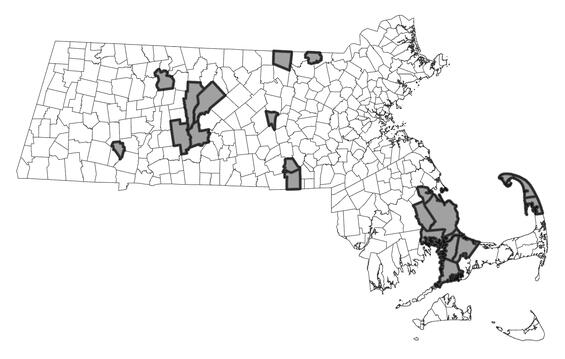

Eastern hog-nosed snakes are known from 9 mainland counties (Franklin, Hampshire, Hampden, Worcester, Middlesex, Norfolk, Bristol, Plymouth, and Barnstable) below 300 m (984 ft) elevation. Hog-nosed snakes have not been recorded from any offshore islands in Massachusetts (e.g., islands in Dukes or Nantucket County). Lazell (1976) suggested that hog-nosed snakes are absent from the outlying islands in Massachusetts and Rhode Island because they are poor dispersers across seawater and they arrived in New England after the major islands were isolated from the mainland by postglacial sea level rise. However, the species appears to be relatively salt-tolerant and has even been observed in the surf and ocean at Cape Cod as well as at Assateague Island, Maryland. There are also no records from Essex County, although the species is well documented in portions of the Nashua River watershed in Middlesex County and adjacent New Hampshire.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Eastern hog-nosed snakes in occupy a variety of habitats in Massachusetts (both forested and non-forested). They demonstrate a preference for edge habitats and mosaics of scrub and herbaceous vegetation. Hog-nosed snakes are frequently associated with pitch pine-scrub oak forests, ericaceous scrub, and other habitats underlain by glacial outwash, particularly those with sandy or sandy-loam soils, but they also are known to occur in areas dominated by mature white pine. Hog-nosed snakes favor areas with surface debris or woody with abundant sources of amphibian prey (especially toads, as noted earlier). Eastern hog-nosed snakes have also been observed sharing hibernacula with other snake species, such as North American racers and milksnakes.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Hog-nosed snakes seem to be susceptible to declines caused by habitat fragmentation as well as habitat succession. The primary cause of recent declines is habitat loss and fragmentation, with adults lost to roadkill and depredation by small carnivores. However, the loss of early-successional foraging and nesting habitats has also been detrimental to populations. Some population declines are likely related to the declines in reproductive success associated with increasing closed-canopy habitats due to succession. On Cape Cod, hog-nosed snakes are still killed by homeowners who think they are venomous and may be surprised by the snake’s startling anti-predator displays. Dispersal capability is probably poor, given an aversion to crossing paved roads, high nest site fidelity, and potential for roadkill and incidental killing.

Some of the most extensive populations known occur on federally-managed land of the Cape Cod National Seashore. Because of the high level of automobile, bicycle, and pedestrian traffic within known areas of occurrence, the species should be closely monitored on Cape Cod to assess adult mortality.

Wetland habitat loss—including loss of functional, seasonal ponds—also affects the hog-nosed snake by reducing habitat quality for its primary prey species, toads. There have undoubtedly been losses of hibernacula to development. Some populations may also have been reduced by over-collection, and certainly many individuals are killed by people needlessly frightened by their extraordinary bluff behavior. It is likely that the unnaturally high-density populations of small- to mid-size “human commensal” carnivores, such as raccoon, skunk and fox, associated with human development, are also a threat to this snake. Studies are required to determine more about the abundance, distribution, and core habitat requirements of the species.

Adult eastern hog-nosed snake from Cape Cod, Barnstable County, Massachusetts. Photo: Scott Buchanan

Conservation Action Plan

More than any other snake species in Massachusetts, hog-nosed snakes are associated with sandplain communities on deep sand outwash and coastal dunes, and benefits from strategic management of these areas where they occur. Current habitat management activities on several major protected areas—including vegetation management, forestry, and prescribed fire—appear to support eastern hog-nosed snake conservation. In particular, restoration of pitch pine-scrub oak communities with prescribed fire and forestry improve habitat quality for the species at other locations. However, as noted by New Hampshire Fish and Game Department (2015), habitat management activities need further evaluation to confirm that they result in more stabilize populations. Road mortality hotspots must be identified, mapped, and mitigated. Long-term quantitative monitoring should be implemented.

References

Akresh, M.E., D.I. King, B.C. Timm, and R.T. Brooks. 2017. Fuels management and habitat restoration activities benefit Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes (Heterodon platirhinos) in a disturbance-dependent ecosystem. Journal of Herpetology 51(4): 468–476.

Buchanan, S.W., B.C. Timm, R.P Cook, and R. Couse. 2012. Heterodon platirhinos. Hibernacula Site Fidelity. Herpetological Review 43(3): 493–494.

Buchanan, S.W. 2012. Ecology of the Eastern Hognose Snake (Heterodon platirhinos) at Cape Cod National Seashore, Barnstable County, Massachusetts. MS thesis, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ.

Buchanan, S.W., B.C. Timm, R.P. Cook, and R. Couse. 2013. Heterodon platirhinos. Reproduction. Herpetological Review 44(4): 691–692.

Buchanan, S.W., B.C. Timm, R.P. Cook, R. Couse, and L.C. Hazard. 2016. Surface activity and body temperature of Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes (Heterodon platirhinos) at Cape Cod National Seashore. Journal of Herpetology 50(1): 17–25.

Buchanan, S.W., B.C. Timm, R.P. Cook, R. Couse, and L.C. Hazard. 2017. Spatial ecology and habitat selection of eastern Hog-nosed snakes. Journal of Wildlife Management 81(3): 509–520.

Buelow, C. 2007. Atlas of Sandplain Communities in the Upper Ware River and Eastern Quabbin Watersheds. Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program; Westborough.

Chen, X., S. Huang, P. Guo, G.R. Colli, A.N. Montes de Oca, L.J. Vitt, R.A. Pyron, and F.T. Burbrink. 2013. Understanding the formation of ancient intertropical disjunct distributions using Asian and Neotropical hinged-teeth snakes (Sibynophis and Scaphiodontophis: Serpentes: Colubridae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 66(1): 254–261

Cooper, W.E., and S. Secor. 2007. Strong response to anuran chemical cues by an extreme dietary specialist, the eastern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon platirhinos). Canadian Journal of Zoology 85: 619–625.

Goulet, C., J. Litvaitis, and M. Marchand. 2015. Habitat associations of the eastern hognose snake at the northern edge of its geographic distribution: should a remnant population guide restoration. Northeastern Naturalist 22(3): 530–540.

Hawthorne, B. 2017. Montague Plains Habitat Plan (Draft). Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MassWildlife); Westborough, MA.

Klemens, M. 1993. Amphibians and Reptiles of Connecticut and Adjacent Regions. State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut Bulletin 112.

LaGory, K.e., L.J. Walston, C. Goulet, R.A. van Lonkhuyzen, S. Najjar, and C. Andrews. 2009. An examination of scale-dependent resource use by Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes in Southcentral New Hampshire. The Journal of Wildlife Management 73(8): 1387-1393.

Lazell, J.D. 1976. This Broken Archipelago: Cape Cod and the Islands, Amphibians and Reptiles. Quadrangle; New York.

Lazell, J.D. 1979. Deployment, dispersal, and adaptive strategies of land vertebrates on Atlantic and Gulf Barrier Islands. Pp. 415–419 in: Linn, R.M. (ed). Proceedings of the First Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks, Volume 1. Transactions and Proceedings Series No. 5, U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service; Washington, DC.

Latreille, P.A. In Sonnini, C.S., and P.A. Latreille. 1801. Histoire naturelle des reptiles, avec figures dessinées d'apres nature; Tome IV. Seconde Partie. Serpens. Crapelet. Paris. 410 pp. (Heterodon platirhinos, new species, pp. 32–37.)

Michener, M.C., and J.D. Lazell. 1989. Distribution and relative abundance of the Hog-nosed snake, Heterodon platirhinos, in eastern New England. Journal of Herpetology 23(1): 35-40.

Mirick, P.G., T. French, and J. Kubel. 2016. Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife; Westborough, MA.

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department (NHFG). 2015. New Hampshire Wildlife Action Plan, Appendix A. Eastern Hognose Snake, Heterodon platirhinos. At website: http://www.wildlife.state.nh.us/wildlife/profiles/wap/reptile-easternhognosedsnake.pdf

Pook, C.E., U. Joger, N. Stümpel, W. Wüster. 2009. When continents collide: Phylogeny, historical biogeography and systematics of the medically important viper genus Echis (Squamata: Serpentes: Viperidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol 53(3): 792–807.

Robson, L.E., and G. Blouin-Demers. 2013. Eastern Hognose Snakes (Heterodon platirhinos) avoid crossing paved roads, but not unpaved roads. Copeia 2013: 507–511.

Seburn, D. 2009. Recovery strategy for the eastern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon platirhinos) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Park Canada Agency, Ottawa. vi+24pp.

Vanek, J., R. Mullins, and D. Wasko. 2014. Heterodon platirhinos. Reproduction/Nest Site Fidelity. Herpetological Review 45(4): 710–711.

Vanek, J.P., and D.K. Wasko. 2017. Spatial ecology of the eastern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon platirhinos) at the northeastern limit of its range. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 12: 109–118.

Zheng, Y. and J.J. Wiens 2016. Combining phylogenomic and supermatrix approaches, and a time-calibrated phylogeny for squamate reptiles (lizards and snakes) based on 52 genes and 4162 species. Mol Phylogenet Evol 94(Pt B): 537–547, and appendices.

Contact

| Date published: | March 14, 2025 |

|---|