- Scientific name: Opuntia cespitosa Rafinesque

- Synonyms: Opuntia rafinesquei Engelm

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Photo credit: Kelly Omand

Prickly pear cactus is a native perennial in the cactus family (Cactaceae) that spreads along the ground and grows to 0.3 m (12 in) tall. The pads (technically called cladodes, which are stem segments) are in chains of 2 to 6 with a flat (broad) surface parallel to the ground. Majure et al. (2017) described the cladodes as “strongly glaucous-green (gray-green) when developing, aging dark green or light gray-green, cross-wrinkling during the winter months, 3.8 to 18.7 cm × 3.2 to 11.3 cm (1.5-7.4 in × 1.3-4.4 in), 4-19.2 mm (0.16-0.76 in) thick.” The pads have areolas, small circular areas where spines are attached, that are arrayed in rows across the pad. These have tiny, barbed, deciduous spines called glochids that are the reason you should never touch or handle these pads. The glochids are reddish to dark amber, and with age, turn light to dark brown. The flowers are large and showy, with yellow tepals that look like petals. The center of the flower is red to dark red to orange-red and crimson. The fruits are smooth, up to 4.5 cm (1.8 in) in length, shaped like an upside-down bowling pin, fleshy and green initially, becoming brownish-rusty-red as they mature. This species can reproduce by seed or vegetatively by detachment of the pads. The pads have sharp spines that one would expect to see on a cactus. These are smooth, 1 to 2 (occasionally 3) per areole (most commonly 1), and 1.5-4.3 cm (0.6-1.7 in) long.

Similar species

For a long time, this species was assumed to be a variety of Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Raf., but thanks to careful work by the Majure et al. (2017), this has been separated out. The two species are very similar except the flower color of O. humifusa is strictly yellow and the pads are generally without spines.

Photo credit: Kelly Omand

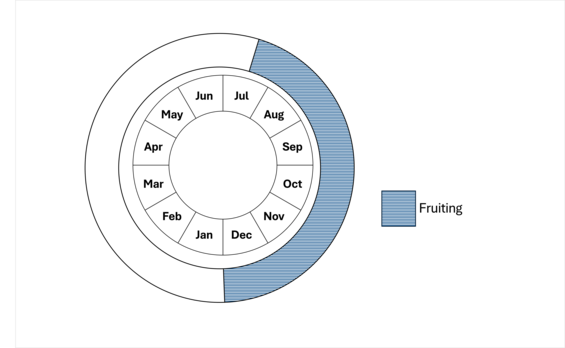

Life cycle and behavior

These are considered shrubs and have visible tissue all year long, though the winter, the plant has a very shriveled appearance. It is best seen when flowering, in early July.

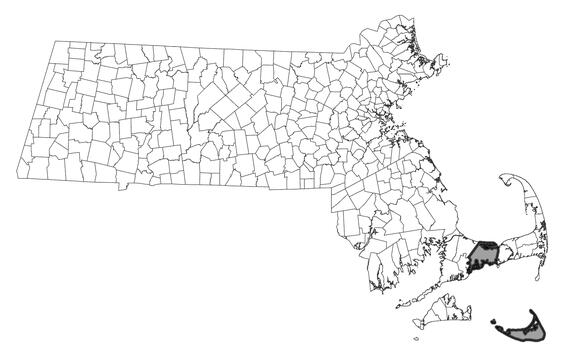

Population status

MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program has documented four populations from two counties: Barnstable, and Nantucket. The Barnstable population has several plants within a square meter with a total of 12 stems counted in 2017. The Nantucket population has over a thousand plants in three populations.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Distribution and abundance

Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut have the only populations in New England. It occurs in New York, Pennsylvania, west to Arkansas, Missouri, and Illinois, south to Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia, and north to Ontario. The center of the population is Kentucky and Tennessee (Major et al. 2017).

Habitat

Massachusetts populations grow on sand very near the ocean shore, in very open to scrubby habitat, to grasslands and heathlands. Some are in partial shade of cedars and taller shrub patches, while others grow at the back edge of dunes, or at the margin of salt marsh (Omand pers. comm. 2025). Associated species include red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), bayberry (Morella pensylvanica), dunegrass (Ammophila breviligulata), seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), wavy hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa), shaved sedge (Carex tonsa), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), reindeer lichen (Cladonia spp.), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), field wormwood (Artemisia campestris), eastern false willow (Baccharis halimifolia) and poor-man's pepperweed (Lepidium virginicum).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The primary threat to this species in Massachusetts is shoreline and harbor development, coastal erosion, and sea-level rise which is expected to continue as the climate warms. In the Northeast US, the sea level has risen about 0.3 m (12 in) since the year 1900, faster than the rate around the world (Staudinger et al. 2024). Roads and other development in the coastal region should avoid populations of eastern prickly pear. Fencing and re-directing of trails and off-road vehicle roads may help to protect known populations. Saltspray rose (Rosa rugosa), spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe), and horned poppy (Glaucium flavum) are the typical non-native/invasive species threats (Omand pers. comm. 2025).

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Much more survey work is needed to establish numbers on all populations given the recent taxonomic change to establish this as a separate species. After that, given sea-level rise and severe storms are both increasing, surveys should be completed every other year.

Management should consist of shrub and invasive species control as well as preventing excess off-road vehicle use.

Research needs

While natural threats such as storm surges may not be avoidable, how best to move plants to safer locations with appropriate habitat should be a research consideration.

References

Cullina M, Connolly B, Sorrie B, Somers P (2011) The vascular plants of Massachusetts: a county checklist, 1st revision. Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany, Eighth (Centennial) Edition—Illustrated. American Book Company, New York.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines A (2020) In the Field with Arthur Haines: Recognizing a New Species of Prickly Pear

iNaturalist 2025. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. Accessed 25 March 2025

Majure LC, Judd WS, Soltis PS, Soltis DE (2017) Taxonomic revision of the Opuntia humifusa complex (Opuntieae: Cactaceae) of the eastern United States. Phytotaxa 290:1–65. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.290.1.1

Omand, Kelly. Plant Research Ecologist & Botanist. Nantucket Conservation Foundation 2025 email to Robert Wernerehl

POWO (2023). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ Retrieved 24 March 2025

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Weakley, A.S., and Southeastern Flora Team. 2025. Flora of the southeastern United States Web App. University of North Carolina Herbarium, North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill, U.S.A. https://fsus.ncbg.unc.edu/main.php?pg=show-taxon-detail.php&lsid=urn:lsid:ncbg.unc.edu:taxon:{A4D74459-3843-4CED-BFC5-5F288F089C79}. Accessed Mar 25, 2025.

Contact

| Date published: | April 15, 2025 |

|---|