- Scientific name: Pantherophis alleghaniensis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Adult eastern ratsnake on shagbark hickory in Massachusetts.

The eastern ratsnake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) is a common species over most of the eastern United States from Georgia to Vermont and southern Ontario, west to Illinois and Louisiana. In Massachusetts, the ratsnake is severely imperiled and unlikely to be observed except at a handful of mountainous locations in central and western Massachusetts. Ratsnakes are the longest snake native to Massachusetts and are placed within the family Colubridae. Adult ratsnakes in Massachusetts are large, muscular, and shiny black. Despite being mostly black, adult ratsnakes often have traces of white skin between the scales, and the underside or ventral surface is checkered with light and dark, becoming gray towards the tail. Ratsnakes’ chin and throat are whitish and uniform. Ratsnakes’ eye has a black pupil surrounded by a light-colored margin, a trait most prominent in juveniles. Ratsnakes have scales that are weakly keeled, which is an important distinguishing characteristic. Adults typically have 23-27 scale rows near the head and 17-21 near the tail. The anal plate is usually divided or partially divided. Juveniles have a distinct dorsal pattern of black, diamond-shaped blotches on a pale gray background, with the same ventral pattern as adults. By the time a Massachusetts ratsnake reaches about 100 cm (39 in) it is dark-colored and loses the juvenile pattern. Juvenile ratsnakes have large eyes. Males and females are identically colored males have longer tails (16-19% of total body length) than females (14-18% of total body length). Large adults can exceed 200 cm (79 in) in length. Historical specimens near Springfield reportedly measured 213-236 cm (84-93 in), and the largest recorded ratsnake was 256.5 cm (101 in). Hatchlings average 29-37 cm (11-14.5 in) in length.

Similar Species

Young eastern ratsnakes, with their "saddle" patterns, could be mistaken for milk snakes (Lampropeltis triangulum) or young North American racers (Coluber constrictor). A key identifying feature of juvenile eastern ratsnakes is their white-margined eyes. Also, especially with a magnifying glass, it’s possible to see that young ratsnakes have keeled scales (scales with ridges) especially visible along the middle of their backs (both milk snakes and North American racers have smooth scales without keels). Further, North American racers also have dark eyes. Adult ratsnakes are also frequently confused with adult North American racers because they are both large, black snakes. However, adult ratsnakes are much heavier-bodied, have keeled scales, and tend to be less active (note: racers are aptly named). North American racers are typically very alert and quick to flee, while eastern ratsnakes appear more sluggish and slower to react. Also, racers are found across large areas of the state in both rocky uplands and sandy outwash areas; ratsnakes are confined to a few mountainous habitats in central Massachusetts and the Connecticut River Valley. Some ratsnakes could be confused with timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) because they sometimes vibrate their tails rapidly when alarmed, producing a sound similar to a rattlesnake's rattle when rustling dry leaves. However, ratsnakes lack a true rattle, and rattlesnakes are seldom entirely black. Also, rattlesnakes have a stockier body and overall appearance with a broad, triangular head, and vertical or cat-like pupil.

Detail view of keeled scales on an adult eastern ratsnake from Massachusetts.

Adult eastern ratsnake whitish chin and keeled scales.

Life cycle and behavior

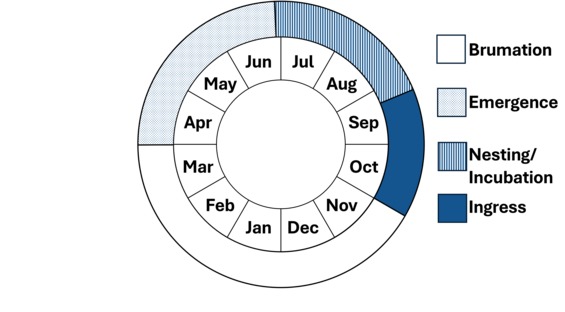

After emerging from their overwintering sites in April, ratsnakes disperse into adjacent woodlands and forest edges to feed and mate. Ratsnakes are highly arboreal and spend days on end in the forest canopy, especially in spring and early summer, but they also forage on the ground and will sometimes enter rodent burrows. Ratsnakes of all ages are heavily arboreal. While some individuals remain in forested habitats throughout the active season, many utilize edge habitats (such as those associated with powerlines or utility rights-of-way) or old field habitats. Limited published data exists on the movements of ratsnakes in Massachusetts, but evidently their annual movements can easily exceed 1-2 km (0.6-1.2 mi). Ratsnakes enter hibernacula in late fall (typically by late October) and emerge by mid-April. In very warm years, they may emerge earlier and return to their dens later than usual.

Mating likely occurs following emergence in the spring, from late April through May. Ratsnakes lay eggs and do not give live birth. After a brief gestation period, females lay 8-12 eggs in decaying piles of vegetation or compost, rotting stumps, large tree snags, or hollow logs. Some animals probably nest in debris or junk in old fields. Eggs hatch in late summer.

Ratsnakes are carnivorous, like most snakes, and feed on small mammals, birds, amphibians, and other snakes. More than 25 species of birds have been documented as ratsnake prey; a Massachusetts adult disgorged a clutch of mallard eggs.

Juvenile eastern ratsnake showing characteristic pattern.

Distribution and abundance

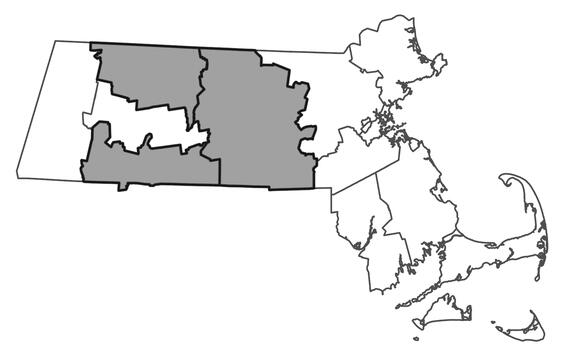

The eastern ratsnake ranges from central Georgia north to Vermont and southern Ontario, and west to Illinois and Louisiana. At the northern edge of the range, ratsnakes are found in Connecticut, southwestern Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and central Vermont. In Massachusetts, extant populations are scattered in the Connecticut River valley and southern Worcester County. Historical records suggest a wider distribution within Massachusetts in the past. J.A. Allen's 1868 account notes they were "not rare along the Connecticut... from Longmeadow to Mt. Tom," estimating their population to be about "one-half as numerous as the common black snake [Black Racer]." This suggests a significant decline in the Eastern Ratsnake population within Massachusetts since that time, though quantifying that decline precisely requires further research.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The ratsnake's distribution in Massachusetts (and New England more generally) is probably limited both by the availability of suitable hibernation sites (hibernacula) and also by the legacy of historical land use and deforestation. Today, there is more suitable habitat for ratsnakes than is occupied. New England represents the northern extent of their distribution, and it is likely that ratsnakes are thermally and climatically stressed, meaning that their overwintering sites are crucial for survival. Overwintering locations are often located in rocky areas or talus slopes with southern exposures to maximize warmth from the winter sun and provide nearby basking areas in early spring and late fall. These sites are occasionally shared with other snake species such as the North American racer, copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix), and timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), and often encompass crevices, rocky outcroppings, talus slopes, and cliffs. Ratsnakes also are found in mixed forests, including stands with large, senescent snags that may provide suitable nesting sites, as well as adjacent fields, thickets, and other early successional habitats that support their prey.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Historic ratsnake habitat in Massachusetts.

Historic ratsnake habitat in Massachusetts.

Threats

Ratsnakes occur in Massachusetts on the very edge of their vast range in North America. Here, they are more susceptible to myriad and synergistic threats, especially those associated with habitat degradation and fragmentation, roadkill, and collection as pets. Some individuals are killed in netting around gardens or koi ponds. Others are likely killed during routine mowing of powerline rights-of-way and open hayfields and pastures near wooded mountainous areas. Further development of frontage lots near occupied mountainous areas results in “ecological traps”—open, attractive areas associated with lawns and gardens where individual snakes are more likely to be killed by cars, mowers, or people. It’s likely that the succession of open farmland to second-and third-growth forest has reduced the availability of “edge” habitats, leading snakes to venture into residential areas to forage and thermoregulate. Ratsnakes are popular in the pet trade because they are docile, large, and attractive. Public interest in reptiles has increased in recent decades, intensifying collection pressure on wild populations. Because these snakes rely on specific hibernacula and return to the same sites annually, collectors can easily reduce a local population by targeting these dens. In Massachusetts, it is illegal to capture or possess an eastern ratsnake, regardless of its origin.

Conservation Action Plan

Because of the complex range of threats affecting ratsnakes at the individual and population level, successful conservation of ratsnake populations in Massachusetts will require multilateral approach that heavily involves key landowners. The following management recommendations are crucial for the species' long-term survival within the state:

Inventory and assessment: The full extent of ratsnake distribution in Massachusetts is not known. There are reports of ratsnakes in areas that historically have not had documented populations. Whether these represent real, natural, or introduced occurrences should be investigated. Once new populations or subpopulations are identified, follow-up work should focus on identifying and mapping overwintering sites, basking trees, and nesting features (such as large, senescent trees).

Protect overwintering areas and restore connectivity: Most known overwintering locations are on protected public land (but not all). It is critical to acquire remaining dens for conservation purposes, and to promote connectivity between clusters of dens and other key habitat features.

Habitat management for prey: Small-scale agriculture, forestry practices, and utility line management that create and maintain edge habitats during the inactive season (to reduce the chance of ratsnake mortality from machinery and mowers) can benefit eastern ratsnakes by supporting populations of rodents and small mammals. This type of management should be implemented thoughtfully so as to minimize harm to individual snakes.

Roadway mitigation: Several roadways in Massachusetts are the site of repeated, frequent ratsnake mortality. Several of these areas are within mosaics of fields, forest, and residential areas. Future work should attempt to lessen roadway mortality through habitat management, landowner outreach, signage, and seasonal public service announcements.

Public outreach and education: Public education campaigns are needed to raise awareness about ratsnakes, their ecological importance (as predators of tick-carrying rodents), and the threats they face in the Commonwealth. An effective outreach program could reduce persecution of snakes and promote helpful land management. As part of a renewed effort to increase familiarity with ratsnakes, managers should emphasize that capturing or possessing ratsnakes in Massachusetts is illegal and explain the negative impacts of the pet trade on wild populations.

Interagency cooperation: Effective management of ratsnakes will require sustained and creative collaboration between MassWildlife and Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, as well as state wildlife agencies in Connecticut and Vermont, and conservation organizations, landowners, and researchers.

References

Allen, J.A. 1868. Catalogue of the Reptiles and Batrachians found in the Vicinity of Springfield, Mass., with Notices of all the other species known to inhabit the State. Proc. Bos. Soc. Nat. Hist. (XII), pp. 171–204.

Blouin-Demers, G., and P. J. Weatherhead. 2001. Habitat use by Black Rat Snakes (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta) in fragmented forests. Ecology 82(10): 2882–2896.

Dreslik, M.J., W.E. Clark, and C.A. Phillips. 2004. Conservation of the Black Rat Snake ( Elaphe o. obsoleta) in a fragmented landscape. Wildlife Society Bulletin 32(1):134–142.

Klemens, M.W. 1993. Ecology of the Black Rat Snake (Elaphe o. obsoleta) in southeastern New York. Journal of Herpetology 27(4):428–439.

Klemens, M. W., 1993. Amphibians and Reptiles of Connecticut and Adjacent Regions. State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut. Bulletin No.12, 318 pp.

Seigel, R.W., and N.M. Degenhardt. 1991. Hibernacula of the Black Rat Snake (Elaphe o. obsoleta) in the northern part of its range. Journal of Herpetology 25(4):480–483.

Contact

| Date published: | April 17, 2025 |

|---|