- Scientific name: Carphophis amoenis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Eastern wormsnakes (Carphophis amoenus) are one of Massachusetts’ smallest, most secretive, and range-restricted species of snake. Wormsnakes are slender and small: they average about 10–20 cm (4–8 inches) in length. Wormsnakes have uniform coloration ranging from tan to gray or dark brown, with a pinkish ventral surface or belly. The pinkish belly coloration covers the first two scale rows. Wormsnakes have a pointed nose, small eyes, and a short tail with a blunt tip, and typically have 13 scale rows with smooth scales and a divided anal plate. Wormsnakes are not venomous; they are placed within the family Colubridae which encompasses most Massachusetts snake species. Young wormsnakes resemble adults, but they are darker brown with a brighter pink belly. Based on limited research in Kentucky, female wormsnakes are larger in mass than males, weighing around 6.6 g (0.23 oz) on average, compared to 4.6 g (0.16 oz) for males. Females also tend to have more ventral scales (112–150) than males (106–138). Males have longer tails relative to their body length and a greater average number of subcaudal scales (25–40) compared to females (14–36).

Similar species

Wormsnakes are extremely localized in Massachusetts and should not be expected outside of the Connecticut River watershed in Hampden County. However, within this small area, three other snake species could be confused with the wormsnake:

Dekay’s brownsnake (Storeria dekayi): This grayish-brown, drab snake has a faint pattern of parallel spots on its back. Brownsnakes lack the pointed snout and glossy appearance of the wormsnake.

Ring-necked snake (Diadophis punctatus): This elegant little snake has a cream- or yellow-colored collar around its neck and a whitish or cream-colored belly. Wormsnakes lack the prominent collar seen in Diadophis.

Red-bellied snake (Storeria occipitomaculata): Young red-bellied snakes have three pale spots around their neck that may form a collar, and are grayish to black in coloration. Red-bellied snakes also lack the wormsnake’s slightly pointed nose.

Life cycle and behavior

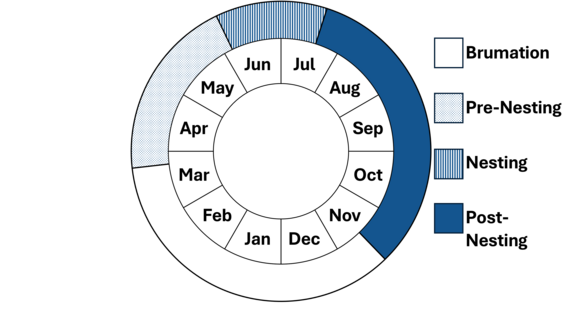

Wormsnakes in Massachusetts are secretive, fossorial (burrowing/tunneling) snakes that live mostly underground. Wormsnakes are not aggressive and tend to burrow or seek cover when threatened or captured. Wormsnake activity is concentrated in the spring and summer months, and mating likely occurs in the spring. Wormsnakes may be nocturnal during the summer activity season. Elsewhere in their northeastern range, wormsnakes may be observed crossing roads on humid or rainy summer nights. They burrow deeply in substrate during extended dry periods. Wormsnakes can live for more than four years in the wild. They primary feed upon worms, but also eat fly larvae, other insects, slugs, and snails. They are eaten by other snakes (such as North American racers), large amphibians, small mammals, and birds. Wormsnakes are oviparous (they lay eggs), and they deposit 2–6 eggs (typically 4–5) in soil, decaying woody debris, or under rocks from mid-June through early July. Older and larger females tend to lay larger clutches. Eggs hatch in approximately 50 days, with emergence likely occurring in August or September. Little is known about wormsnakes’ spatial ecology but they are thought to have small home ranges. Males likely travel greater distances than females. There is evidence of aggregation in some areas, with high population densities reported from some southern states, but populations densities in Massachusetts are probably lower—and populations more isolated and fragmented—than in areas to the south.

Distribution and abundance

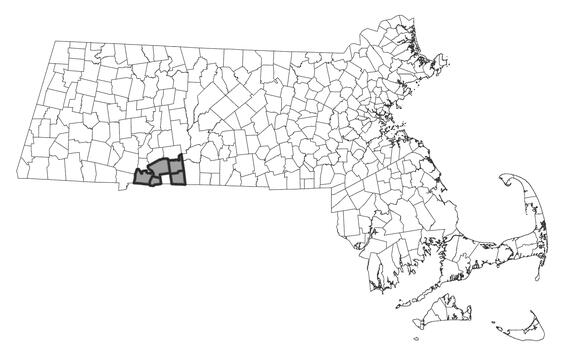

The wormsnake has a fairly large distribution, extending from the southern Connecticut River valley of Massachusetts to South Carolina along the east coast, and west from southeastern New York and Pennsylvania through West Virginia and eastern Tennessee, to northern Alabama and Georgia. Isolated populations also exist in Lake Erie, southern Ontario, southeastern New England, and north-central North Carolina. In Massachusetts, wormsnakes are extremely range-restricted, and have been documented only from five towns within Hampden County. Correspondingly, the wormsnake is listed as a Threatened species under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA), because of its rarity and localized distribution.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Wormsnakes prefer moist, but not saturated, sandy soil with abundant cover, such as woody debris, leaf litter, or rocks. They inhabit a variety of environments, including deciduous hardwood forests, mixed pine-hardwood forests, pine forests, and early successional fields. They are often found in ecotone areas near woodland and wetland borders or woodland and grassland intersections. Microhabitat soil moisture typically ranges from 10–83%, most often 21–30%, with a pH range of 5–6.9, similar to that preferred by their primary prey, earthworms. They tolerate a wide range of temperatures but show a preference for 23°C (73°F). Eastern wormsnakes are often encountered in gardens, compost piles, weedy pastures, and wooded areas.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The wormsnake is probably most threatened by the loss and degradation of habitat along with associated vehicle and machine mortality. They are probably also affected by the incremental loss of early-successional nesting habitats. Wormsnakes have limited dispersal capability, as described above, and high nest site fidelity (a tendency to return to the same area to nest in subsequent years) which further increase their vulnerability. Further, wormsnakes are likely threatened by increased population density of human-commensal carnivores, such as raccoons, skunks, and foxes. Wormsnakes are generally poorly understood and difficult to study without stressing or injuring animals or damaging their favored refuges and hiding spaces.

Conservation Action Plan

The wormsnake's secretive nature and extremely limited distribution in Massachusetts present challenges for its conservation. Ongoing surveys are needed to determine the most effective and least detrimental survey methods, as well as the optimal timing for detecting this species. Further research should clarify the full extent of its distribution and habitat associations in Hampden County, as well as seasonal shifts in habitat use, population size, and population dynamics. The existing population require additional land protection along with improved connectivity to other suitable areas across roadways. Prime habitat, as it is identified, should be prioritized for protection through fee acquisition or conservation restrictions. Regulatory review under MESA can provide some additional support known populations by minimizing further fragmentation of their habitat. This species probably responds well to the creation of early successional habitat through prescribed fire and/or mowing, especially if these activities occur while individuals are bromating below ground.

References

Conant, R., and J.T. Collins. 1991. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians—Eastern and Central North America. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA.

DeGraaf, R.M., and D.D. Rudis. 1983. Amphibians and Reptiles of New England; Habitats and Natural History. The University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA.

Ernst, C.H., and R.W. Barbour. 1989. Snakes of Eastern North America. George Mason University Press, Fairfax, VA

Ernst, C.H., and E.M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Books, Washington, DC.

Klemens, M.W. 1993. Amphibians and Reptiles of Connecticut and Adjacent Regions. American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY.

Linzey, D.W., and M.J. Clifford. 1981. Snakes of Virginia. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, VA.

McLeod, R. and G.J. Edward. 1998. Response of herpetofaunal communities to forest cutting and burning at Chesapeake Farms, Maryland. American Midland Naturalist 139(1):164-177.

Mitchell, J.C. 1994. The Reptiles of Virginia. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Orr, J. M. 2007. Microhabitat Use by the Eastern Worm Snake, Carphophis amoenus. Herpetological Bulletin 97.

Russell, R.K., and H.G. Hanlin. 1999. Aspects of the ecology of worm snakes (Carphophis amoenus) associated with small isolated wetlands in South Carolina. Journal of Herpetology 33(2):399- 344.

Tyning, T. F. 1990. A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Write, A.H., and A.A. Wright. 1957. Handbook of Snakes of the United State and Canada, Volume I. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

Contact

| Date published: | April 1, 2025 |

|---|