- Scientific name: Carex grayi J. Carey

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Perigynia (photo credit: Tom Groves)

Gray’s sedge (Carex grayi) is a perennial sedge (family Cyperaceae) that grows in tufts of solitary or multiple stems up 1.1 m (~3.6 ft) high. It can be found in rich, mesic soils of forests, calcareous seepage swamps, marshes, banks, and wet meadows, within riparian systems. The most recognizable features of this species (which is within Carex section Lupulinae) is its unearthly-looking spherical flowering spike, comprising large inflated perigynia, which radiate outward in all directions. Gray’s sedge was named in honor of the widely renowned American botanist Asa Gray (1810–1888), who founded the vascular plant herbarium at Harvard College in Cambridge, MA.

To positively identify Gray’s sedge and other members of the genus Carex, a technical key should be consulted. Sedges of the genus Carex have small unisexual, wind-pollinated flowers borne in spikes. The staminate (male, pollen-bearing) flowers are subtended by a single flat scale; the pistillate (female, ovule-bearing) flowers are subtended by one flat scale (the pistillate scale) and are enclosed by a second sac-like modified scale, the perigynium. Following flowering, the achene (a dry, indehiscent, one-seeded fruit) develops within the perigynium. The morphological characters of these reproductive structures are important in identifying plants of the genus Carex to species.

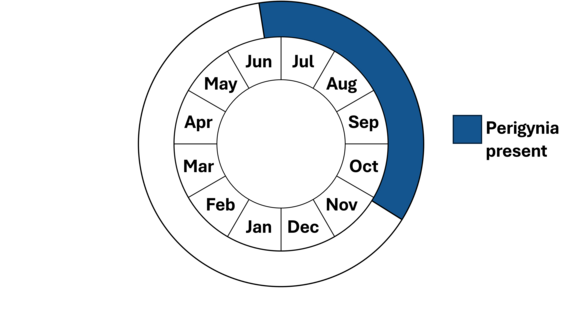

Gray’s sedge is a clump-forming plant with short rhizomes and triangular culms (reproductive stems). The pale or gray-green leaves are 4-11 mm (0.16-0.43 in) wide with persistent basal reddish-purple sheaths. The subtle narrow peduncled staminate spike is located above one or two large spherical pistillate spikes on the same stem. The densely flowered female spikes are subtended by long, leaf-like bracts that do not have sheaths. The pistillate spike comprises 8-35 diamond-shaped radiating perigynia, 12.5-20 mm (0.5-0.79 in) long. The perigynium surface is dull and strongly veined. Perigynia are subtended by pistillate scales that are roughly egg-shaped and often tipped with a rough awn (~7 mm [0.28 in] long). Achenes are sessile, 3-angled and not thickened on angles, with persistent but withering, and sometimes contorted, styles. Identifiable flowering spikes are present throughout much of the summer.

Bladder-sedge (Carex intumescens), also a member of Carex section Lupulinae, is similar to Gray’s sedge but has fewer perigynia (mostly 1-12 per spike), the perigynia surfaces are lustrous (not dull), and are rounded (not wedge-shaped) at the base. In addition, the perigynia in Gray’s sedge point in all directions including downwards, while those of bladder-sedge do not point downwards.

Reddish purple basal sheath (photo credit Peter Dziuk of MinnesotaWildflowers.info)

Life cycle and behavior

Gray’s sedge is a perennial plant growing in tufts of solitary or multiple stems and is wind-pollinated. Its distinctive inflorescence can be observed from mid-summer into fall. The large, air-filled perigynia are likely to float for extended periods, taking their achenes away from the parent plant.

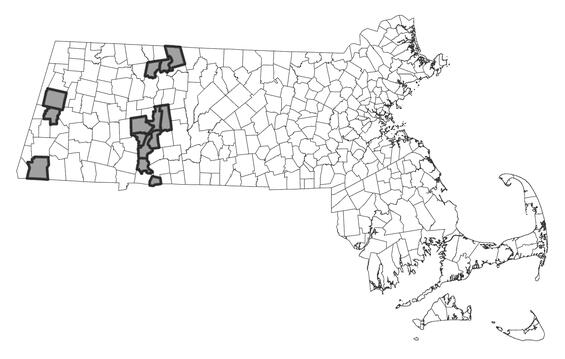

Population status

Gray’s sedge is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA) as Threatened. All listed species under MESA are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. There are 23 populations of gray’ sedge verified since 1999, occurring in Berkshire, Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire Counties. There are no known historical occurrences. Approximately 5 of the populations are ranked as good to excellent.

Distribution and abundance

Gray’s sedge is known from eastern-central Canada (Ontario, Quebec), western New England States, south to Florida, southwest to Oklahoma, and throughout much of the Midwest to Kansas. In New England, it is considered imperiled in Massachusetts and vulnerable in Vermont. Connecticut hasn’t ranked it. It is not known to occur in Maine, New Hampshire or Rhode Island.

Distribution in Massachusetts

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

In Massachusetts, Gray’s sedge inhabits the moist alluvial soils of floodplain forests and adjacent meadow edges of large rivers. Many current populations in the state are found within floodplain forests along oxbows or in low depressions or swales where they favor lower slopes and bottoms. Associated woody species include silver maple (Acer saccharinum), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa; Special Concern), and native shrubs such as wild black currant (Ribes americanum; Watch List). Associated sedges include stiff sedge (Carex amphibola), hop-sedge (Carex lupulina), Tuckerman’s sedge (Carex tuckermanii; Endangered), foxtail sedge (Carex alopecoidea; Threatened), and Davis’s sedge (Carex davisii; Endangered). Other herbaceous associates include wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) and ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

photo credit: Matt Arsenault

Threats

Threats to populations of Gray’s sedge include changes in the hydrology of the major river floodplains where Gray’s sedge occurs. Agricultural activities in floodplains can impact the sedge and non-native invasive plant species that might out-compete Gray’s sedge. Fragmented landscapes can make it difficult for Gray’s sedge to survive and spread its pollen and seed from one population to another. Extreme weather events which are predicted to become more common with climate change (Staudinger et al. 2024) may wash out plants on smaller streams and rivers. This has been observed with one previously robust population that was substantially reduced after a major storm event and plants were washed away in floodwaters. Small populations are at risk of extirpation via stochastic events. Isolated populations may be subject to inbreeding depression.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

All rare species need periodic surveys and monitoring. Gray’s sedge populations need to be surveyed to determine if its population and habitat has experienced any changes, including altered hydrology, invasions of non-native species, or extreme flooding events. Surveys should occur every 5 to 10 years. The best time to survey is late June to October.

Management

The exact management needs of Gray’s sedge are not known. As with all rare species, however, maintaining habitat quality is essential. Flooding probably plays a role in maintaining habitat quality and is an important dispersal mechanism; thus, land use changes that affect the hydrologic regime should be avoided or carefully evaluated. Further, water quality should be preserved; water quality degradation due to inputs of nutrients from fertilizers or animal waste could change the water and soil chemistry, and favor establishment of exotic or aggressive generalist species. Gray’s sedge habitat should be monitored for non-native invasive species. Invasive plants can out-compete native plants for nutrients and light, excluding them over time. Some invasive plants, such as garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) are allelopathic, meaning they can change the soil chemistry to inhibit the viability native plants. Exotic species of concern in the floodplain plant communities of Gray’s sedge are woody species such as Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), and Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), as well as the herbaceous invasive plants garlic mustard, moneywort (Lysimachia nummularia), and reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea). If exotic plants are invading Gray’s sedge habitat, a plan for control should be constructed. All active management within the habitat of a rare plant population (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under MESA and should be planned in close consultation with the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

Research needs

One of the primary concerns for this species (as well as many of the other rare plants) is the isolation of the populations and whether the isolated smaller populations are subject to inbreeding depression sufficient to cause genetic damage. Genetic research looking for signs of inbreeding and decreased resilience is a primary need for this species.

References

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

Native Plant Trust. 2014. NORM Phenology Information.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 3/19/2025.

POWO (2025). "Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 3/19/2025."

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Contact

| Date published: | March 26, 2025 |

|---|