- Scientific name: Chelonia mydas

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Threatened (North Atlantic DPS) (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) are one of three hard-shelled sea turtles (family Cheloniidae) found regularly in Massachusetts (a fourth Cheloniid, the hawksbill sea turtle, is extremely rare, if native at all). Green turtles are a remarkable component of Massachusetts’ marine fauna because they are typically distributed at more southerly latitudes. Green sea turtles are one of the larger species of sea turtle found in New England, but their heads are smaller than that of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Adult green sea turtles mature at a carapace length of 70–100 cm (27–29 inches). Green sea turtles are olive, gray, greenish, brown or reddish-brown in color, with a smooth shell. Juvenile and subadult green sea turtles sometimes have light, radiating streaks on each scute. Green sea turtles have four costal scutes (large keratinous plates on the side of their carapace) and only one pair of prefrontal scales between the eyes. Hatchling green sea turtles have a black carapace, a whitish plastron, and white margins to the shell and limbs. Green sea turtle tracks have symmetrical flipper marks, a tail drag in the center of the track, and a track width of 95–144 cm (37–56 in.). The name “green turtle” reportedly refers to the color of its fat.

Similar species

Green turtles can be differentiated from the other three species of hard-shelled sea turtle found in Massachusetts by characteristics of coloration, head scalation, and shell characteristics (note that hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata)are extremely rare in the northern Atlantic, making misidentification in Massachusetts less likely).

Kemp's ridley sea turtle: Kemp's ridleys are the smallest sea turtles in the Atlantic and the smallest species of sea turtle found in Massachusetts. Kemp’s ridleys have a round carapace and a more triangular head shape when compared to green sea turtles, and they have two or more pairs of prefrontal scales between their eyes (green sea turtles have 1 pair). Kemp’s ridleys possess five costal scutes rather than the four found on green sea turtles.

Hawksbill sea turtle: Extremely uncommon in northern waters, hawksbills have a brown carapace with overlapping or shingle-like (imbricate) scutes, with a serrated rear margin. Hawksbills also have a narrow, pointed head with a beak resembling a raptor’s beak. Like green sea turtles, hawksbills have four costal scutes, but they have two pairs of prefrontal scales between their eyes (again, green turtles have only one).

Loggerhead sea turtle: Loggerheads reach larger sizes than green sea turtles in the Atlantic and this is generally true for individuals found in Massachusetts, as well. Loggerheads have a large head with powerful jaws and a reddish-brown shell with five costal scutes (again, compare to the four found in green turtles).

Life cycle and behavior

Like other Cheloniid (hard-shelled) sea turtles, green sea turtles have a long lifespan exceeding 40–50 years in the wild. Likely, green sea turtles can achieve ages 80 years or more. Like other sea turtles, green sea turtles reach sexual maturity only after a decade or more, typically between 13–20 years. Female green sea turtles come ashore from southern waters to nest at night, on sloping beaches with minimal human disturbance, and can lay multiple clutches of eggs within a single nesting season. As is the case with most turtles, clutch size is correlated with body size and can range from about 80–150 eggs. Eggs incubate in warm beach sand for about 45–75 days before hatching. Like all marine turtles, the sex of hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the nest during incubation: warmer temperatures tend to produce females, while cooler temperatures tend to produce males.

Green sea turtles are omnivorous as hatchlings and juveniles, feeding on marine worms, crustaceans, insects, algae, and seagrass. As green sea turtles grow, their diet transitions to primarily seagrass and algae, including at least nine species of Gracilaria and eight species of Sargassum. Adult green sea turtles are unique among sea turtles in being predominantly herbivorous.

Young adult green sea turtle.

Distribution and abundance

Green sea turtles are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. In the Atlantic Ocean, green sea turtles nest on beaches distributed between 30˚N and 30˚S latitude, in waters that maintain a temperature above 20˚C year-round. Nesting aggregations are documented in Florida, Yucatán, Costa Rica, several Caribbean islands, and other locations. Green sea turtles in the western Atlantic range more broadly than their nesting beaches and are known to occur from Massachusetts to around Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Most green sea turtle nesting in the United States occurs in Florida, but they have nested as far north as the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and in 2011, a green sea turtle nested at Cape Henlopen State Park in Delaware. In 2022, an apparent nesting attempt was documented on Nantucket, Massachusetts (although Massachusetts is not currently considered an active nesting area for green sea turtles).

Habitat

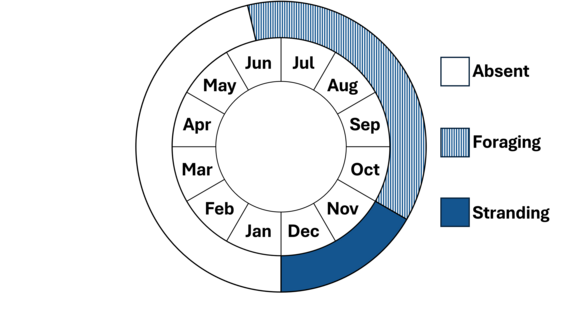

Green sea turtles are found in shallow coastal lagoons, inlets, bays, and estuaries, often near seagrass beds. Massachusetts nearshore waters probably serve as a developmental habitat for juvenile green sea turtles. During late fall and early winter, juvenile green sea turtles are frequently found stranded on the southern and eastern beaches of Cape Cod Bay due to cold-stunning. Cold-stunning is a phenomenon where, for complex reasons, turtles remain in Massachusetts nearshore waters at the end of the season, until they lose the ability to swim and control their movements. They end up stranded on beaches during high tides in November and December.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Green sea turtles are threatened by numerous well-documented factors throughout their range, but some of the primary threats in Massachusetts include:

Cold-stunning: As noted, juvenile green sea turtles are susceptible to cold-stunning in Cape Cod Bay during the late fall and early winter.

Vessel strikes: Collisions with boats and other vessels can cause severe injury or death to green sea turtles.

Fisheries interactions: Green sea turtles can become entangled in fishing gear, leading to drowning or serious injury.

Pollution: Green sea turtles can ingest plastic that can interfere with digestion. Like all sea turtles, green sea turtles are negatively affected by oil spills and other forms of coastal pollution.

Many of the green sea turtles that are cold-stunned in Massachusetts are juvenile turtles.

Conservation and management

Considering that green sea turtles occur in Massachusetts at the very northern edge of their range and are threatened by complex and synergistic factors, key management needs include:

Cold-stunning response: The annual effort by Mass Audubon's Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, New England Aquarium, and other partners to rescue cold-stunned turtles on Cape Cod should continue. This program involves searching beaches for stranded turtles after high tides and transporting them to wildlife hospitals such as the New England Aquarium for long-term medical care and rehabilitation.

Research and monitoring: Green sea turtle habitat use and population data for Massachusetts have been minimally studied. Research and monitoring are important for informing management decisions and assessing the effectiveness of conservation efforts. This may involve tagging studies, genetic analysis, and population surveys.

Fisheries entanglement: Ongoing research and managed response to minimize the frequency of green sea turtle interactions with fishing gear in Massachusetts waters is valuable to reduce entanglement.

Monitoring sightings in open water: In addition to the stranded sea turtle response, MassAudubon coordinates a sea turtle sightings hotline and corresponding website (seaturtlesightings.org) which tracks observations of all Massachusetts’ five sea turtles (living and dead). This provides a useful tool for tracking distributional information.

Here are some hotlines that can be used to report sea turtle sightings or strandings:

- Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary's Sea Turtle Hotline: 508-349-2615, option 2

- NOAA Fisheries Marine Animal Hotline: 866-755-6622

- New England Aquarium's Marine Animal Hotline: 617-973-5247

Acknowledgements

MassWildlife acknowledges the expertise of Dr. Charles Innis (New England Aquarium), who contributed substantially to the development of this fact sheet.

References

Hirth, H.F. 1997. Synopsis of biological data on the Green Turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus 1758). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Washington, D.C.

Komoroske, L.M., M.P. Jensen, K.R. Stewart, B.M. Shamblin, and P.H. Dutton. (2017) Advances in the application of genetics in marine turtle biology and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:156

Wyneken, J., Lohmann, K., and Musick, J. A. (2013). The Biology of Sea Turtles, Vol. 3. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Contact

| Date published: | April 2, 2025 |

|---|