- Scientific name: Lepidochelys kempii

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Endangered (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Kemp’s ridley cold-stunned in Massachusetts.

Massachusetts has become the site of an unusual phenomenon of global significance in marine biology over the past 50 years: each year in late autumn, several hundreds of Kemp's ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys kempii) wash up on Cape Cod beaches, where they would certainly die without intervention. Instead, through the sustained intervention of multiple partner organizations, hundreds of these turtles are rehabilitated and returned to the wild. But it is during these cold-strandings in November and December that the general public is most likely to observe a Kemp’s ridley up close.

Kemp’s ridley is the smallest species of sea turtle in the world; adults grow to a length of about 60 cm (24 in) and weigh around 45 kg (100 lb). Kemp’s ridley have an olive-gray or reddish-brown carapace (upper shell) and the plastron (lower shell) is lighter in color (an example of countershading, where the top of the animal is dark and bottom light, a phenomenon common in marine vertebrates). In young individuals, the carapace is distinctly circular, being nearly equal in width and length. Young turtles also have prominent ridges on the shell. Like other cheloniid sea turtles (hard-shelled sea turtles), Kemp's ridleys have paddle-like front flippers. In Kemp’s ridleys, each flipper has a single claw, while their rear flippers possess two claws. Their heads are small and triangular, featuring a hooked beak and two pairs of prefrontal scales above and between the eyes. Hatchling ridleys emerge from their nests (in Mexico and Texas) with a black carapace and plastron.

Similar species

As noted above, Kemp’s ridleys are most likely to be detected in Massachusetts on Cape Cod during November–December when they are the predominant species stranded during cold-stunning events. Cold-stunning tallies for recent years suggest that Kemp’s ridleys outnumber green sea turtles and loggerheads by more than 10:1. Globally, the Kemp’s ridley is most similar to the olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), which ranges much farther south (and has never been reported from Massachusetts) but which differs from the Kemp’s ridley by usually having more than five costal scutes. Within Massachusetts, it's usually straightforward to distinguish Kemp’s ridley from the other hard-shelled sea turtle species (Cheloniidae):

Loggerhead sea turtle: In Massachusetts, the loggerhead is usually larger than the Kemp's ridley, with a reddish-brown carapace and a proportionally large head. Like the Kemp’s ridley, the loggerhead also has five costal scutes.

Green sea turtle: The green turtle has a smooth, heart-shaped carapace that is olive-brown in color, and has four costal scutes (not 5) and a serrated lower jaw.

Hawksbill sea turtle: The hawksbill is of questionable status in Massachusetts and is almost never found so far north. However, the hawksbill is similarly sized as the Kemp's ridley, with a brown carapace that has overlapping (imbricate) scutes. Like the ridley, hawksbills have four costal scutes.

Diamondback terrapin: Though not a sea turtle (terrapins are emydids, related to freshwater turtles such as map turtles), this brackish-water turtle can b encountered in coastal embayments of Buzzards Bay and Cape Cod. Most terrapins are smaller than the Kemp’s ridleys that wash ashore in Massachusetts, and they have an ornately-patterned grey or brown carapace with a unique diamond-shaped pattern. Terrapins lack the prominent front flippers of the hard-shelled sea turtles.

Life cycle and behavior

The Kemp's ridley is unique among North Atlantic sea turtles for its "arribadas"—mass nesting events where thousands of females gather to lay their eggs on a single beach. In 2014, a total of 10,986 nests were recorded across the three primary nesting beaches in Tamaulipas, Mexico—a promising sign of recovery at a site where 42,000 females once nested in a single day in the 1940s but which had declined to only 200 nests in the largest arribada by 1988. The average clutch size of Kemp’s ridley is about 100 eggs, with incubation taking 45-70 days. Some females nest every year, laying approximately 2.5 clutches per season. Kemp's ridleys are thought to reach sexual maturity around 10-16 years of age. Their lifespan is unknown, but may track with the closely related olive ridley, which is estimated to reach ages over 50 years.

The adult diet of Kemp’s ridley sea turtle primarily consists of crustaceans and mollusks, including spider crabs, shrimps, snails, and sea stars. They also occasionally consume jellyfish and sea plants. Hatchlings, on the other hand, inhabit a vastly different environment. They migrate to the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico, where they live amongst Sargassum seaweed, and hundreds of juveniles migrate up to Massachusetts waters between the ages of 1–4 years; many are cold-stunned in the fall as temperatures drop. At this stage, they transition to an adult diet and move to shallower coastal habitats.

Distribution and abundance

The Kemp's ridley sea turtle primarily resides in North American waters, frequenting the Gulf coasts of Mexico and the United States, and along the Atlantic coast as far north as Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Kemp’s ridleys typically inhabit muddy or sandy bottom habitats in the nearshore and inshore waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico. While there have been a few records of Kemp's ridleys in the waters off Ireland, the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, and in the Mediterranean Sea, most of the population remains concentrated in North America. Nesting for this species occurs exclusively on beaches bordering the Gulf of Mexico, with the three primary nesting sites located in Tamaulipas, Mexico. Kemps’ ridleys also nest at Padre Island, Texas, and are known to have nested in Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

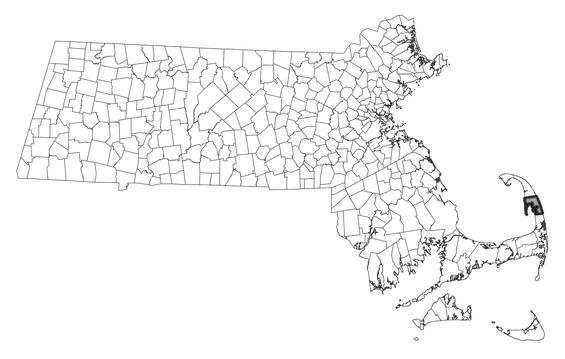

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The Kemp's ridley sea turtle holds the unfortunate distinction of being both the rarest and most endangered sea turtle in the North Atlantic, yet paradoxically, it is (by far) the most frequently encountered sea turtle in Massachusetts. Sightings of healthy, active Kemp's ridleys in Cape Cod Bay during the summer are rare: most encounters with this species in Massachusetts involve small juveniles that have been washed ashore along an 80 km (50 mi) stretch of coast from Barnstable to Provincetown. These strandings typically occur in November and December when water temperatures plummet. The cold-stunning phenomenon, which renders sea turtles incapacitated and stranded at the high tide line, begins to affect small Kemp's ridleys when water temperatures fall below 18°C (65°F), becoming more severe as temperatures continue to drop. Once temperatures reach 15°F (50°F), most Kemp's ridleys in the area are affected. Tragically, when temperatures fall below 4°C (40°F), turtles that wash ashore are often already dead. It’s uncommon for live turtles to wash ashore after January 1.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Most strandings of cold-stunned Kemp’s ridley occur along Cape Cod Bay, Barnstable County, Massachusetts.

Threats

Like all sea turtles, Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are threatened by numerous well-documented factors throughout their range, including drowning in shrimp nets, entanglement in fishing gear, pollution such as oil spills, as well as nest depredation by vertebrate and invertebrate predators. Historically, egg collection by humans was a problem that has now been largely addressed. Historically, an estimated 42,000 females nested in a single day at the primary nesting beach at Rancho Nuevo, Tamaulipas, Mexico, but by 1988 only 200 females came ashore during the largest documented nesting event (or “arribada”). Ongoing conservation efforts since the 1990s and stricter enforcement at nesting beaches have resulted in population recovery. In Massachusetts the most significant source of mortality is probably cold-stunning in late autumn. Cold-stunning events are likely to become more frequent and severe with climate change, underscoring the need to continue managing that phenomenon through coordinated response and rehabilitation.

Kemp’s ridley cold-stunned on a Massachusetts beach.

Conservation and management

In response to the cold-stunning phenomenon, staff and volunteers from Mass Audubon's Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary conduct an annual search of the beaches after every high tide during the late fall and early winter. All recovered turtles are brought to the Sanctuary for initial assessment and emergency care. Live turtles are then transported to the New England Aquarium for more thorough medical evaluations and treatment. Every year, most stranded turtles that are medically stabilized are transferred to other aquaria and care facilities as far away as Texas and Florida once they are stable. During the 1980s, approximately ten Kemp's ridley sea turtles were recovered annually, but since 2000, the average has risen to several hundred turtles per year. In 2024, the final tally of Kemp’s ridleys washing ashore in Massachusetts was 684, but much larger events have occurred such as the stranding season of late 2014, during which over 1,150 Kemp's ridley sea turtles recovered on Cape Cod (157 in a single day).

Here are some hotlines that can be used to report sea turtle sightings or strandings:

- Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary’s Sea Turtle Hotline: (508) 349-2615, option 2

- NOAA Fisheries Marine Animal Hotline: (866) 755-6622

- New England Aquarium’s Marine Animal Hotline: (617) 973-5247

- Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies’ Disentanglement Hotline: 800-900-3622 (mostly to disentangle leatherbacks)

References

Covelo P, Nicolau L, Lopez A. 2016. Four new records of stranded Kemp’s ridley turtle Lepidochelys kempii in the NW Iberian Peninsula. Mar Biodiver Rec 9:80.

Ernst, C.H., and J. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore.

Komoroske, L.M., M.P. Jensen, K.R. Stewart, B.M. Shamblin, and P.H. Dutton. (2017) Advances in the application of genetics in marine turtle biology and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:156

Mayne, B., A.D. Tucker, O. Berry, and S. Jarman. 2020. Lifespan estimation in marine turtles using genomic promoter CpG density. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0236888.

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and SEMARNAT. 2011. Bi-National Recovery Plan for the Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii).

Renaud, M.L. & Williams, J.A. (2005). Kemp's ridley sea turtle movements and migrations. Chelonian Conservation Biology 4(4): 808–816.

Contact

| Date published: | April 17, 2025 |

|---|