- Scientific name: Dermochelys coriacea

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Endangered (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) was once thought of as a casual or infrequent visitor to northern waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Today, it’s clear that this species makes regular and routine migrations to New England and the Canadian Maritime Provinces in search of its favored invertebrate food items, oceanic jellyfish. Leatherbacks are the only surviving member of the monotypic family Dermochelyidae, which likely arose during the late Cretaceous or early Tertiary. Leatherbacks are the largest living turtles and are a truly remarkable component of the Massachusetts fauna.

Leatherbacks are easily distinguishable from all other sea turtles by their bluish, slate-gray, or black rubbery carapace with pronounced ridges and lack of carapace scutes. Seven ridges run front to back on its carapace (including a lateral ridge on both sides), and small white splotches sporadically appear across the entire body. The leatherback’s carapace (upper shell) is comprised of interconnected dermal bone (osteoderm) covered by connective tissue and fat. The carapace tapers to a bluish point above the tail. The leatherback’s plastron or ventral surface is pinkish-white, contrasting with the darker carapace (an example of countershading, seen frequently in marine vertebrates). Individual leatherbacks also have a deeply notched jaw with two cusps.

Leatherbacks have longer front flippers in proportion to their body when compared to other sea turtles, and their rear flippers have a distinctive paddle-like shape. Adult leatherbacks average 1.2–1.8 m (4–6 ft) in shell length, though some individuals exceed 2 m (6.5 ft), and can weigh between 295–907 kg (650–2,000 lb). Hatchlings average between 5.6–6.4 cm (2.2–2.5 in) and like the adults, stand apart from cheloniid sea turtles because of their smooth, leathery skin and blackish, dark blue, or dark brown shell, with narrow ridges. Hatchlings are further distinguished by white stripes lining down their carapace and front flippers as long as their shell, marked with white, pink, or blue blotches.

The maximum potential lifespan of the leatherback sea turtle is unknown but is expected to exceed 90 years based on an analysis of cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) density. Other studies also indicate that leatherbacks are potentially very long-lived, regularly exceeding ages of 50 years. Like their life expectancy, there is limited knowledge on the reproductive longevity of leatherbacks, with researchers estimating that they reach sexual maturity around carapace lengths of 150 cm (60 in). Female leatherbacks mature at older ages than males.

Similar species

The leatherback is so distinctive in its appearance that it is unlikely to be mistaken for any other marine vertebrate if the observer gets a clear look at it. The three hard-shelled sea turtle species found regularly in Massachusetts tend to occur here as juveniles or subadults, making the size difference even more striking. The leatherback is the only sea turtle without scutes (keratinous scales on the carapace), it could possibly be misidentified as another sea turtle species when found as skeletonized remains, or could be mistaken for a loggerhead or an ocean sunfish if glimpsed very briefly at the surface. Loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) can reach similar sizes to smaller leatherbacks; however, animals found in Massachusetts are generally much smaller and have rounder shells with scutes. Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) can also have a body structure somewhat like the loggerhead. However, they are also much smaller with a hard carapace and are lighter in color, ranging from green to brown.

Life cycle and behavior

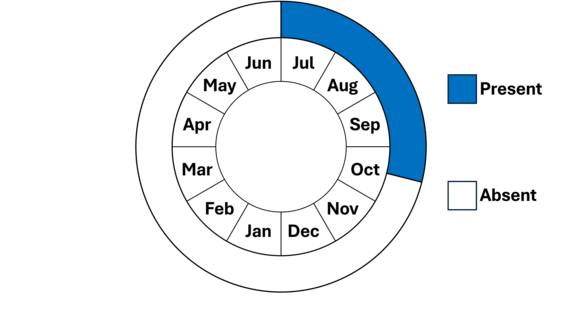

The leatherback sea turtle is widespread in the world’s oceans and is one of the most highly migratory marine vertebrates. This species’ behavior and life history strategies can vary strongly among individuals and populations. Conditions in the Atlantic Ocean have a strong seasonal influence on their migrations and habitat use. Because they have counter-current circulation and can retain metabolically produced heat, leatherbacks regularly venture into the colder waters north of Massachusetts. However, leatherbacks are usually found alive in the temperate latitudes only in the summer and early autumn. During the warmer time of year, leatherbacks forage mainly on Scyphomedusae jellyfish and are known to feed on more than 8 genera of jellyfish, but their diet also consists of squid, snails, bivalves, arthropods, and kelp. Leatherbacks migrate toward more tropical waters in late autumn through spring. Deceased individuals may be found in Massachusetts in any months and the remains sometimes persist through the winter.

Leatherback sea turtles mate from late March to early June in the western Atlantic. Atlantic leatherbacks can travel more than 4,800 km (3,000 miles) to get to their nesting sites, which are distributed primarily in Florida, the Caribbean, Central America, northern South America in the western Atlantic. Leatherback females exhibit nest site fidelity, often coming back to the same beaches in multiple years. Leatherbacks nest on wide, steep, sloped, coarse-grained beaches at night, laying multiple nests within a few weeks. Females will lay around 50–130 eggs per clutch in a large dug out hole, which they will carefully cover back up with sand. Often, a significant proportion of the clutch contains infertile eggs. Like other sea turtles, the temperature of the developing eggs during key thresholds determines the sex of the hatchling, also known as temperature-dependent sex determination or TSD. Eggs that incubate above 31°C (87˚F) will generally be female, and under 27.7°C (81.9˚F) are more likely to become male. The incubation period lasts approximately 60–65 days after deposition.

Once hatched, the hatchlings disperse to the ocean, entering the juvenile phase—a uniquely vulnerable stage of life. During this time, young leatherbacks face numerous predators and can swim thousands of kilometers (> 600 mi) to feeding grounds. Juvenile leatherbacks will spend up to 15 years of their lives in the open ocean. Young leatherbacks will feed on a variety of floating material, mollusks, and marine arthropods. They likely expand their oceanic range as they approach maturity, embarking on large seasonal migrations. Scientists have found that adult leatherbacks can travel over 16,000 km (10,000 mi) annually, and they are often theorized to follow jellyfish availability. Leatherbacks utilize ocean currents to facilitate long-distance movements, and they can descend more than 914 m (3000 ft).

Population status

Leatherback sea turtles are Endangered in Massachusetts and federally. Although the leatherback sea turtle is primarily known as an animal of the open ocean, they also are present in shallow coastal waters during the summer months and early fall to feed on concentrations of jellyfish. Leatherbacks are reported annually along the Massachusetts coast, mostly in Cape Cod Bay, Vineyard Sound, and Nantucket Sound. As noted above, it is now clear that Massachusetts and the Gulf of Maine are key parts of their occupied habitat.

Distribution

The leatherback sea turtle has the largest distribution of any reptile. Populations are distributed worldwide in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Individuals occur naturally in such disparate locations as Newfoundland, Norway, and Alaska to as far south as New Zealand and South Africa.

Habitat

Leatherback sea turtles spend most of their lives in the open ocean or pelagic habitats. During the day, they are often found in deeper waters, and at night, they forage in areas of upwelling, as well as where major currents converge, and in deep-water eddies. Nesting occurs on tropical or subtropical beaches with high energy, grainy sand, and easy access to deep water.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

- Fisheries entanglement: Leatherback sea turtles can become entangled in fishing and trapping gear, leading to drowning or serious injury.

- Pollution: Leatherback sea turtles often ingest plastic that can block their digestive system, and they can be adversely affected by oil spills (like all sea turtles).

- Vessel strikes: Collisions with boats and other vessels can cause severe injuries or death to leatherback sea turtles.

Conservation and management

Management Needs

The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries has helped create and fund a marine turtle disentanglement program which responds to about 10–20 entangled leatherback sea turtles every year. Many of these turtles can be saved by a rapid response, but some are already dead when found or die despite efforts to save them. NOAA has developed regulations designed to protect leatherback turtles, including gear modifications to prevent entanglement, changes in fishing practices, and time/area closures for some gear types. Entangled turtles can be reported to:

- Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies’ Disentanglement Hotline: 800-900-3622 (mostly to disentangle leatherbacks)

- Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary’s Sea Turtle Hotline: 508-349-2615

- NOAA Fisheries Marine Animal Hotline: 866-755-6622

- New England Aquarium’s Marine Animal Hotline: 617 973-5247

References

Dodge, K.L., B. Galuardi, T.J. Miller, and M.E. Lutcavage. 2014. “Leatherback turtle movements, dive behavior, and habitat characteristics in ecoregions of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean.” PloS one 9, 3:e91726.

Ernst, C.H., and J. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore.

Girondot MA, Delmas VI, Rivalan PH, Courchamp FR, Prevot-Julliard AC, Godfrey MH. Implications of temperature-dependent sex determination for population dynamics. Temperature-dependent sex determination in vertebrates. 2004:148-55.

Komoroske, L.M., M.P. Jensen, K.R. Stewart, B.M. Shamblin, and P.H. Dutton. (2017) Advances in the application of genetics in marine turtle biology and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:156

Mayne, B., A.D. Tucker, O. Berry, and S. Jarman. 2020. Lifespan estimation in marine turtles using genomic promoter CpG density. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0236888.

Miller, J.D., 2017. Reproduction in sea turtles. The Biology of Sea Turtles, Volume I, pp.51-81.

National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Endangered Species Act status review of the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Protected Resources and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Thomé, J.C., Baptistotte, C., Moreira, L.M.P., Scalfoni, J.T., Almeida, A.P., Rieth, D.B. and Barata, P.C., 2007. “Nesting biology and conservation of the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, 1988–1989 to 2003–2004.” Chelonian Conservation and Biology 6, 1:15–27.

Wyneken, J., Lohmann, K., and Musick, J. A. (2013). The Biology of Sea Turtles, Vol. 3. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Contact

| Date published: | April 1, 2025 |

|---|