- Scientific name: Caretta caretta

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Threatened (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) are one of three hard-shelled sea turtles (family Cheloniidae) found regularly in Massachusetts (a fourth cheloniid, the hawksbill sea turtle, is extremely rare, if native at all). Loggerheads are very large as full-grown adults—second only to the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Correspondingly, loggerheads also tend to be the largest hard-shelled sea turtles found in Massachusetts. Loggerheads have elongate to heart-shaped shells that are a reddish-brown color. As their common name implies, the loggerhead has a remarkably large head and stocky neck when compared to the hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) or the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). The large head and powerful jaws enable loggerheads to feed on hard-shelled prey, including moon snails, channeled and knobbed whelks, and a variety of crab species. Adults are about 90 cm (3 ft) and 70 kg (250 lb). Their front flippers have dark streaks and two claws on the anterior end.

Similar species

Loggerheads can be differentiated from the other three hard-shelled sea turtle species found in Massachusetts by their overall coloration, head scalation, and shell characteristics (note that hawksbill sea turtles are extremely rare in the northern Atlantic, making misidentification in Massachusetts less likely).

Kemp's ridley sea turtle: Kemp's ridleys are the smallest sea turtles in the Atlantic and the smallest species of sea turtle found in Massachusetts and are generally smaller than the loggerheads found stranded on Massachusetts beaches. Kemp’s ridleys have a round carapace and a more triangular head shape when compared to loggerheads, but like loggerheads they can have two pairs of prefrontal scales between their eyes. Also like the loggerhead, Kemp’s ridleys have five costal scutes. Kemp’s ridleys are more grayish than the reddish-brown loggerhead.

Hawksbill sea turtle: Extremely uncommon in northern waters, hawksbills have a brown carapace with overlapping or shingle-like (imbricate) scutes, with a serrated rear margin. Hawksbills also have a narrow, pointed head with a beak resembling a raptor’s beak. Unlike the loggerhead, which has five costal scutes, hawksbills have four costal scutes. However, like loggerheads they have two pairs of prefrontal scales between their eyes.

Green sea turtle: Both loggerheads and green sea turtles can be bulky, brownish sea turtles, and the most obvious difference between the two species is that green sea turtles have four pairs of costal scutes, while loggerheads have five. As already noted, loggerheads are generally larger than green sea turtles and have a more reddish-brown carapace. Loggerheads possess a relatively larger head.

Life cycle and behavior

Like other Cheloniid (hard-shelled) sea turtles, loggerheads have a long lifespan that can exceed 40–50 years in the wild. Like green sea turtles, loggerheads can achieve ages well over 50 years or more. Loggerheads are completely adapted to marine life and only return to beaches for nesting between the months of April through September, with a peak during June and July. Nests incubate for about 46 to 65 days; hatchlings emerge at night. Females mature at 12–20 years and can produce multiple clutches of eggs per year. Neonates and small juveniles live on the surface of the ocean, allowing the current to carry them along the Atlantic seaboard. As subadults, loggerheads return to waters off the southeastern United States where they feed on mollusks, crabs, and invertebrates.

Distribution and abundance

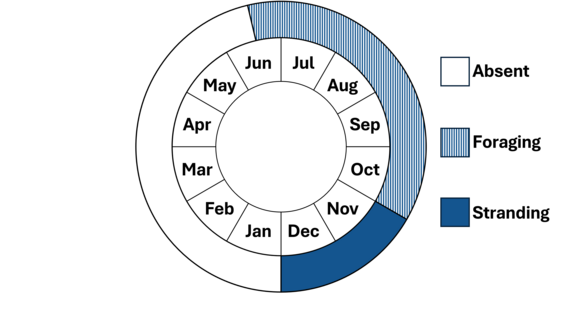

Loggerhead sea turtles are the most common sea turtle along the southeast coast of the United States. Atlantic loggerheads are found around the Bahamas in winter; however, their primary habitat includes the southeastern coast of the United States, extending to South America and eastward toward Africa and the Mediterranean. On the U.S. Atlantic Coast, loggerheads nest on open beaches from North Carolina to the west coast of Florida. Loggerheads make extensive migrations from their nesting beaches to foraging areas on the continental shelf and move northward during the summer as the water temperatures increase to 20–23C˚ (68–73°F). These temperatures allow a few adults to occasionally move as far north as Long Island Sound, the waters south of Cape Cod, and into Cape Cod Bay. A few nest each year as far north as Virginia and loggerheads have rarely nested as far north as Maryland and New Jersey.

Habitat

Loggerhead sea turtles are found primarily in shallow coastal waters, including canals, waterways, lagoons, inlets, bays, and estuaries. Massachusetts nearshore waters may serve as a developmental habitat for subadult loggerhead sea turtles, but this is poorly understood. During late fall and early winter, juvenile loggerhead sea turtles are frequently found stranded on the southern and eastern beaches of Cape Cod Bay due to cold-stunning. Cold-stunning is a phenomenon where, for complex reasons, turtles remain in Massachusetts nearshore waters at the end of the season, until they lose the ability to swim and control their movements. They end up stranded on beaches during high tides in November and December.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Adult loggerhead sea turtle foraging. Photo: ayeleev on iNaturalist.org, used with permission.

Threats

Loggerheads are threatened by numerous well-documented factors throughout their range, but some of the primary threats in the North Atlantic include:

Cold-stunning: As noted, juvenile loggerhead sea turtles are susceptible to cold-stunning in Cape Cod Bay during the late fall and early winter.

Vessel strikes: Collisions with boats and other vessels can cause severe injury or death to loggerheads turtles.

Fisheries interactions: Loggerheads can become entangled in fishing gear, leading to drowning or serious injury.

Conservation and management

Considering that loggerheads turtles occur in Massachusetts at the very northern edge of their range and are threatened by complex and synergistic factors, key management needs include:

Cold-stunning response: The annual effort by Mass Audubon's Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, New England Aquarium, and other partners to rescue cold-stunned turtles on Cape Cod should continue. This program involves searching beaches for stranded turtles after high tides and transporting them to wildlife hospitals such as the New England Aquarium for long-term medical care and rehabilitation. The program benefits loggerheads that come ashore in late fall and winter.

Research and monitoring: Loggerhead turtle habitat use and population data for Massachusetts have been minimally studied. Research and monitoring are important for informing management decisions and assessing the effectiveness of conservation efforts. This may involve tagging studies, genetic analysis, and population surveys.

Fisheries interactions and entanglement: Ongoing research and managed response to minimize the frequency of loggerhead turtle interactions with fishing gear in Massachusetts waters is valuable to reduce entanglement.

Monitoring sightings in open water: In addition to the stranded sea turtle response, MassAudubon coordinates a sea turtle sightings hotline and corresponding website (seaturtlesightings.org) which tracks observations of all Massachusetts’ five sea turtles (living and dead). This provides a useful tool for tracking distributional information.

Here are some hotlines that can be used to report sea turtle sightings or strandings:

- Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary’s Sea Turtle Hotline: (508) 349-2615, option 2

- NOAA Fisheries Marine Animal Hotline: (866) 755-6622

- New England Aquarium’s Marine Animal Hotline: (617) 973-5247

- Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies’ Disentanglement Hotline: 800-900-3622 (mostly to disentangle leatherbacks)

References

Ernst, C.H., and J. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore.

Komoroske, L.M., M.P. Jensen, K.R. Stewart, B.M. Shamblin, and P.H. Dutton. (2017) Advances in the application of genetics in marine turtle biology and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:156

Mayne, B., A.D. Tucker, O. Berry, and S. Jarman. 2020. Lifespan estimation in marine turtles using genomic promoter CpG density. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0236888.

Wyneken, J., Lohmann, K., and Musick, J. A. (2013). The Biology of Sea Turtles, Vol. 3. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Contact

| Date published: | April 1, 2025 |

|---|