- Scientific name: Scirpus longii Fern.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Long’s bulrush (Scirpus longii) is a globally rare, robust sedge (family Cyperaceae) of open peaty wetlands. It has numerous slender leaves, a thick rhizome, and a graceful, arching inflorescence.

Long’s bulrush forms dense, leafy tussocks with long, linear leaves 0.5-0.9 cm (0.25-0.5 in) in width, and stems up to 1.5 m (5 ft) in height. It produces thick, fibrous underground rhizomes 1.3-2.5 cm (0.5-1 in) in width, and primarily reproduces asexually, forming colonies in a ring formation. It produces flowering stems only occasionally. Long's bulrush’s inflorescence is an arching panicle made up of as many as 1,000 spikelets (flowering heads). The base of the panicle is blackish and usually sticky to the touch. The spikelets are 0.8 cm (0.3 in) in length and usually composed of more than 60 flowers. The flowers produce tiny, reddish-brown achenes (one-seeded fruits 0.7-1 mm) that are partially covered by blackish scales (2-3 mm; 0.08-0.12 in. long). At the base of the achenes, there are six long bristles that give the spikelets a hairy or woolly appearance at maturity.

Long’s bulrush is similar in appearance to common bulrush (Scirpus cyperinus), which is very widespread and may be present with Long’s bulrush. Long’s bulrush is differentiated from common bulrush by its thicker rhizome, the blackish basal inflorescence, and the ring formation of its basal leaves. Common bulrush has a rhizome that is 0.6 cm (0.25 in) thick, a pale brown or greenish basal inflorescence, and its basal leaves have a clump (rather than ring-like) formation. In addition, common bulrush blooms later in the season.

Life cycle and behavior

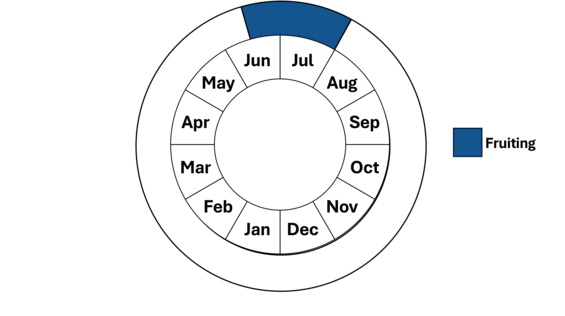

Long’s bulrush is a long-lived perennial species and spreads primarily via rhizomes. Long’s bulrush will rarely flower, typically only following physical stress, such as herbivory damage, drought, fire, or flooding. Flowers of Long’s bulrush are wind pollinated. Within an established population, it spreads primarily by rhizomes, creating circular baskets or larger rings. The circular colonies of Long’s bulrush are long-lived; some are estimated to be over 100 years old. When it does flower, it starts in June, with seeds ripening into mid-August. Seeds may be dispersed by wind as bristles from the flowers remain attached, water may move the seeds, or they may attach to passing animals' fur or feathers. If the rhizomes become fragmented by ice scour or browsing animals, pieces can start new colonies, possibly after being moved by water to new locations.

Population status

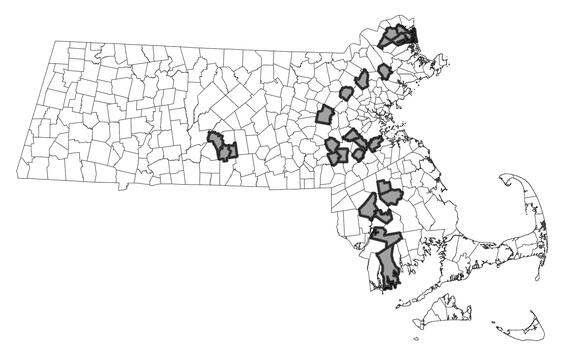

Long’s bulrush is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as Threatened. All listed species are legally protected from killing, collection, possession, or sale, and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. Long’s bulrush has 18 populations verified since 1999 in Bristol, Essex, Middlesex, Plymouth, and Worcester Counties, and is historically known from Suffolk County. It has not been recently relocated at 9 locations.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Distribution and abundance

The limited range of Long’s bulrush extends from Halifax Province in Canada south to New Jersey. It is rare in each state (and province – it only occurs in Halifax in Canada) where it is known to occur and is presumed to be extirpated from Connecticut and New York. In New England, it is critically imperiled in New Hampshire and Rhode Island; and imperiled in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. It is not known from Vermont. It is also considered imperiled in New Jersey. It is considered vulnerable in Halifax (NatureServe 2025).

Habitat

Long’s bulrush inhabits open, peaty wetlands with fluctuating water levels. In Massachusetts, Long’s bulrush is known to occur in acidic fen and wet meadow communities associated with rivers. Associated species include slender woolly-fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa var. americana), Canada bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), marsh-cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), Virginia chain-fern (Woodwardia virginica), large cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon), tawny cotton grass (Eriophorum virginicum), common bulrush (Scirpus cyperinus), button-sedge (Carex bullata), twig-sedge (Cladium mariscoides), Canada rush (Juncus canadensis), bog-willow (Salix pedicellaris), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), and red maple (Acer rubrum).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Threats to Long’s bulrush include changes in the water quality and the natural fluctuating hydrologic regime of its habitat, invasion by exotic invasive plants, and exclusion of fire disturbance. Even as the wetlands where Long’s bulrush occurs are protected, development of adjacent land to agriculture, housing or commercial/industrial sites can impact the hydrology and water quality. Long’s bulrush has low genetic diversity (possibly from its ability to self-pollinate) and may not be able to respond easily to changes in its environment from climate change (warming, meteorologic) (Staudinger et al. 2024).

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Monitoring populations of Long’s bulrush is important, especially when environmental changes, such as dramatic flooding or fire, take place. In addition, habitat sites should be monitored to catch invasions of exotic plant species in the early stages. Species of concern in Long’s bulrush habitat include Common Reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis), Glossy Buckthorn (Frangula alnus), and Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). Although native, common cattail (Typha latifolia) will outcompete Long’s bulrush as water quality deteriorates. Finally, changes in hydrology can lead to an increase in woody species if the habitat becomes drier which will then shade the habitat and prevent the growth of Long’s bulrush.

Long’s bulrush can be identified from its rhizomes from spring through fall, and if in a known location with the population, throughout the year.

Management

As with many rare species, the exact management needs of Long’s bulrush are not known. It is known, however, that Long’s bulrush spreads primarily through asexual reproduction via rhizomes, and that fertile culms are only typically produced following major environmental stress, such as unusually high or low water levels, heavy muskrat herbivory, and fire. Production of wind-dispersed seeds is a desired outcome in management because it enhances the ability of the species to colonize other suitable habitat sites. Though it has been proven that mechanical disturbance (i.e., trampling, and damaging leaves) to Long’s bulrush can bring about flowering, seedling establishment has been low or absent at sites that have not been burned. It appears that burning prepares an optimal seed bed, with a reduction in organic substrate and an absence of woody competitors and thus results in greater success in sexual reproduction. It is expected that the application of highly controlled experimental fires could provide the conditions necessary to elicit flowering and seedling establishment. However, very little is known about the practical application of prescribed burning to manage Long’s bulrush populations. All such active management should be preceded by a site evaluation, which may include an examination of fire history (e.g., from sediment charcoal), and an assessment of the natural community attributes (e.g., hydrologic regime, soils, associated plant community). To avoid inadvertent harm to rare plants, all active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) should be planned in consultation with the Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Research needs

Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. Questions about seed germination and seed storage over winter will need to be answered.

References

Arsenault Matt, Glen H. Mittelhauser, Don Cameron, Alison C. Dibble, Arthur Haines, Sally C. Rooney, and Jill E. Weber. 2013. Sedges of Maine: A Field Guide to Cyperaceae. University of Maine Press, Orono, ME. 712 pp.

Dodds, Jill S. 2022. Scirpus longii Rare Plant Profile. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, State Parks, Forests & Historic Sites, State Forest Fire Service & Forestry, Office of Natural Lands Management, New Jersey Natural Heritage Program, Trenton, NJ. 16 pp.

Drake, N.E.R. and W. A. Patterson III. 1990. Preliminary investigation of fire and vegetation history of Noquochoke wetlands, Bristol County, MA. Unpublished report to NHESP by UMass Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management.

Native Plant Trust. 2014. NORM Phenology Information.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 5/1/2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: Accessed: 5/1/2025.

Rawinski, Thomas J. 2001. Scirpus longii Fern., Long's bulrush. Conservation and Research Plan prepared for the New England Wild Flower Society, Framingham, MA. Available at http://www.newfs.org

Whittemore, Alan T. and Alfred E. Schuyler. Page updated November 5, 2020. Scirpus longii Fernald. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 22+ vols. New York and Oxford. Accessed August 7, 2022 at http://floranorthamerica.org/Scirpus_longii

Contact

| Date published: | May 12, 2025 |

|---|