- Scientific name: Lathyrus palustris L.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Marsh-pea, Lathyrus palustris, is a low-growing, sprawling herbaceous vine in the bean family (Fabaceae), with 2–6 bright purple flowers about 10 cm (4 in) long. Wild peas (Lathyrus species) are similar to vetches (Vicia species) in having compound leaves, climbing tendrils, and stipules—small green leafy bracts at the base of the leaf where it attaches to the stem. Wild peas differ by having fewer and larger leaflets per leaf compared to vetches.

Marsh-pea can be distinguished from other wild peas in Massachusetts by its sharper, finer stipules that are attached along the side to the stem. In contrast, beach vetchling (Lathyrus japonicus) has much broader stipules attached only at the base and bears 6-10 flowers per flower stalk, whereas marsh-pea has only 2-6. Marsh-pea produces legumes for fruits that are only 4-7 mm (0.16-0.28 in) wide. The legumes of beach vetchling are wider at 8-11 mm (0.31-0.43 in) in width.

Life cycle and behavior

Marsh-pea is a perennial plant. It flowers from early June through mid-July.

Population status

Marsh-pea is a species of greatest conservation need and is maintained on the plant watch list. It is likely under-surveyed, but appears to be rare in Massachusetts. There are currently only 3 verified populations observed since 1999 in Essex and Plymouth Counties. An additional 23 observations are now considered historical as they have not been observed within the past 25 years. Besides Essex and Plymouth Counties, Marsh-pea has also been observed in Barnstable, Bristol, Duke, Nantucket, and Suffolk Counties.

Distribution and abundance

Marsh-pea is widespread across Canada and common in the Upper Midwest, St. Lawrence River watershed, and Nova Scotia. It is found along the eastern coastal plain to Georgia, and also along the Pacific coast from Alaska to California. It is rare in many southern states. In New England, it is imperiled in Vermont. No other states, including Massachusetts, have ranked it.

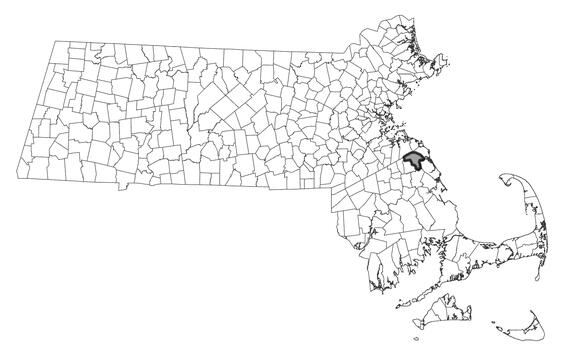

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Marsh-pea typically inhabits wet meadows, salt marshes, shores of water bodies, and wetland edges. In the New England states, it has a wetland status of FACW, indicating it usually occurs in wetlands.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

As a wetland species, marsh-pea is vulnerable to disruptions of the natural hydrologic regime, habitat loss, deer browsing, and the encroachment of invasive species or woody vegetation. Climate change poses additional risks. Nutrient runoff from fertilizers and excess flooding or siltation may promote invasive or aggressive native plants, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), common reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis), cattails (Typha spp.), and reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea).

Conservation

Recommended management includes further surveys to document the species’ abundance and distribution, and the maintenance of its native wetland habitat through practices such as dormant season mowing or prescribed burns to prevent succession by shrubs and trees. All management actions should promote open, sunny wetland conditions. Mowing meadows is a common practice among land managers include our Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Mowing, as opposed to haying, does not remove the cut vegetation, leaving in some places a heavy layer of thatch through which herbaceous plants struggle to grow. Haying removes the cut plant material and is preferred choice for this species and many others. Haying has been reduced in part because there isn’t much demand for late season hay, and secondly the equipment itself has become less common. Mowing former hay meadows is a widespread conservation practice in species-rich European semi-natural grasslands. Once-a-year mowing seems to be the most effective method rather than an interval of every two or three years (Hájková et al. 2022, Milberg et al. 2017). Grazing has also been shown to be beneficial in some circumstances at certain intensity levels with specific livestock (Tälle et al. 2016).

Another important aspect to management of wet meadows is to remove and reduce populations of all invasive species, especially those mentioned in the threat section.In certain situations, prescribed fire is an ideal approach to battling invasives, restoring plant diversity and removing the thatch layer that might result from mowing.

As this plant is under-surveyed, more standard information is needed such as lists of associated species, comments on habitat quality and threats, and assessments of soil conditions and phenology. Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, this strategy could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

Hájková, P., V. Horsáková, T. Peterka, Š. Janeček, D. Galvánek, D. Dítě, J. Horník, et al. 2022. Conservation and restoration of Central European fens by mowing: A consensus from 20 years of experimental work. Science of The Total Environment 846: 157293.

Milberg, P., M. Tälle, H. Fogelfors, and L. Westerberg. 2017. The biodiversity cost of reducing management intensity in species-rich grasslands: Mowing annually vs. every third year. Basic and Applied Ecology 22: 61–74.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 5/23/2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 3/4/2025.

Seymour, Frank C. 1969. The Flora of New England, First edition. Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc. Tokyo, Japan.

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Tälle, M., B. Deák, P. Poschlod, O. Valkó, L. Westerberg, and P. Milberg. 2016. Grazing vs. mowing: A meta-analysis of biodiversity benefits for grassland management. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 222: 200–212.

Contact

| Date published: | April 30, 2025 |

|---|