Ten popular wildlife stories from 2025

- Legacy of a log

- Dance of the American woodcock

- Veggie vandals: Protecting your gardens from wildlife

- Cicada chorus on the Cape

- Paddle, fish, explore!

- Massachusetts turtle online field guide

- Land protection highlights: Winchendon Springs & Rockdale Highlands

- Mystery mammal skull challenge

- A closer look at deer breeding season

- Know your milkweed

Counting birds: Your new holiday tradition

What is the Christmas Bird Count and why is it important?

Looking for a way to give during the holiday season while also enjoying nature? A tradition that started Christmas Day in 1900 is now a long-standing program of the National Audubon Society. People across the state will spend the beginning of the winter counting birds, helping ornithologists gather data that would be difficult to collect on their own.

From December 15 to January 5, the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) will commence in the U.S., Canada, and 18 other countries in the Western Hemisphere. Countries are divided into geographical regions (35 in Massachusetts) and each region will pick a single 24-hour period to count birds.

Data from the CBC can be utilized in many ways, including to monitor trends in bird populations, document range shifts over time, and examine how climate change may impact the winter distributions of birds.CBC data has been used in hundreds of analyses, peer-reviewed publications, and government reports over the decades.

What birds are in MA in December?

There are a variety of feathered friends that can be seen in Massachusetts, including:

- Local residents: chickadees, titmice, many species of woodpeckers, bluebirds, Carolina wren, and many raptors.

- Migrants heading south for winter: kinglets, some raptors, snow bunting, some sparrows.

- Waterfowl: dabbling and diving ducks, especially along coast.

- Irruptive species that are only present in some years: finches like evening grosbeak, red crossbill, white-winged crossbill, redpoll, pine grosbeak, red-breasted nuthatch.

Count birds on a WMA

Many of MassWildlife’s Wildlife Management Areas (WMA) fall within the CBC regions. Below is a table of top WMA locations to count birds. Check out the CBC circle map to sign up and participate. If you aren’t able to get out to a WMA, learn how you can still participate in the CBC.

| CBC Regions | WMAs where you can bird count |

|---|---|

| Athol | Birch Hill WMA, Fish Brook WMA, Lawrence Brook WMA, Millers River WMA, Norcross Hill WMA, Orange WMA, Phillipston WMA, Popple Camp WMA, Stone Bridge WMA, Tully Mountain WMA, Warwick WMA |

| Buzzards Bay | Frances A. Crane WMA, Mashpee Pine Barrens WMA, Mashpee River WMA, Pickerel Cove WMA, Quashnet River WMA, Quashnet Woods State Res. & WMA, Camp Edwards WMA |

| Cape Ann | Castle Neck River WMA, Great Marsh North WMA |

| Cape Cod | Eastham Salt Marsh WMA, Olivers Pond WMA |

| Central Berkshire | Chalet WMA, Day Mountain WMA, Fairfield Brook WMA, George L. Darey Housatonic Valley WMA, Hinsdale Flats WMA, Housatonic River East Branch WMA, Richmond Fen WMA |

| Cobble Mountain | Honey Pot WMA, Southwick WMA, Stage Brook WMA, Tekoa Mountain WMA, Westfield WMA |

| Concord | Boxborough Station WMA, Delaney WMA, Pantry Brook WMA, Whittier WMA |

| Greenfield | Darwin Scott WMA, Flagg Mountain WMA, Green River WMA, Leyden WMA, Montague Plains WMA, Montague WMA, Mt. Toby WMA, Sunderland Islands WMA |

| Groton-Oxbow N.W.R | Bolton Flats WMA, Hunting Hills WMA, Mulpus Brook WMA, Nissitissit River WMA, Squannacook River WMA, Townsend Hill WMA, Unkety Brook WMA |

| Marshfield | English Salt Marsh WMA |

| Martha’s Vineyard | Katama Plains WMA |

| Mid-Cape Cod | Chase Garden Creek WMA, Hyannis Ponds WMA, Old Sandwich Game Farm WMA, Sandwich Hollows WMA |

| Millis | Charles River WMA |

| New Bedford | Haskell Swamp WMA, Mattapoisett River WMA, South Shore Marshes WMA |

| Newburyport | Crane Pond WMA, Martin H. Burns WMA, Salisbury Salt Marsh WMA, Upper Parker River WMA, William Forward WMA |

| Newport County-Westport | Dartmoor Farm WMA |

| Northampton | Brewer Brook WMA, Great Swamp WMA, Lake Warner WMA, Mt. Esther WMA, Mt. Tom WMA, Rainbow Beach WMA, Whately WMA |

| Northern Berkshire | Barton's Ledge WMA, Brodie Mountain WMA, Bullock Ledge WMA, Green River WMA, Misery Mountain WMA, Savoy WMA, Stafford Hill WMA, |

| Plymouth | Camp Cachalot WMA, Cooks Pond WMA, Halfway Pond WMA, Maple Springs WMA, Plymouth Grassy Pond WMA, Red Brook WMA, Se Pine Barrens WMA, Sly Pond WMA, South Triangle Pond WMA |

| Quabbin | Herman Covey WMA, Moose Brook WMA, Muddy Brook WMA, Raccoon Hill WMA, Ware River WMA, Winimusset WMA |

| Southern Bershire | Agawam Lake WMA, Dolomite Ledges WMA, Hubbard Brook WMA, Jug End State Reservation And WMA, Karner Brook WMA, North Egremont WMA, Three Mile Pond WMA |

| Springfield | Facing Rock WMA |

| Sturbridge | Breakneck Brook WMA, Hitchcock Mountain WMA, Leadmine WMA, Mckinstry Brook WMA, Quaboag WMA, Quacumquasit WMA, Rattlesnake Mountain WMA, Richardson WMA, Wolf Swamp WMA |

| Taunton-Middleboro | Copicut WMA, Hockomock Swamp WMA, Mill Brook Bogs WMA, Puddingstone WMA, Purchade Brook WMA, Taunton River WMA |

| Truro | Fox Island WMA, Marconi WMA |

| Tuckernuck Islands | Wasque Point WMA |

| Uxbridge | Chockalog Swamp WMA, E. Kent Swift WMA, Lackey Pond WMA, Mine Brook WMA, Quisset WMA, West Hill Dam WMA |

| Westminster | Ashburnham WMA, High Ridge WMA, Hubbardston WMA, Savage Hill WMA, Templeton Brook WMA |

| Worcester | Mt. Pisgah WMA, Poutwater Pond WMA |

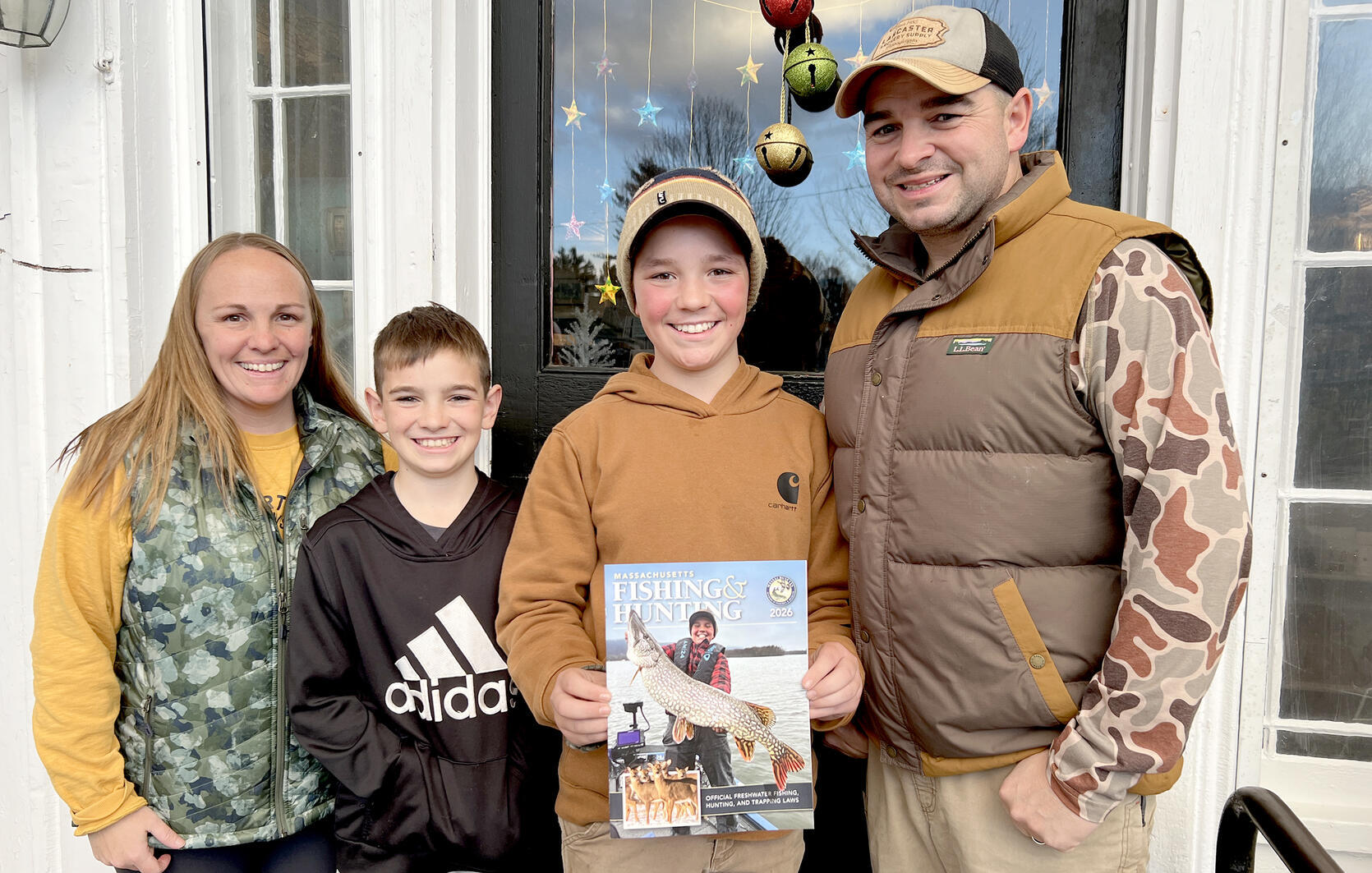

Young angler shines on 2026 guide cover

Next year’s fishing and hunting licenses are now on sale. That means the 2026 Massachusetts Guide to Fishing, Hunting, and Trapping Laws is also available online, at MassWildlife offices, and license vendors. This year’s cover features Kyler Leslie, 14, of Petersham with his gold pin-winning northern pike, caught on the Connecticut River on March 6, 2024. The fish was 39 inches long and weighed 15 pounds.

In 2024, Kyler and his 11-year-old brother Ryker tied as winners of the Angler of the Year award in the youth catch-and-release category of MassWildlife’s Freshwater Sportfishing Awards Program. Each brother caught 23 of the 24 eligible species. The Guide cover photo was selected by the editor of Massachusetts Wildlife magazine, Troy Gipps, who also works with fisheries and wildlife staff each year to update the Guide.

But the story of the cover photo gets even better. When Gipps contacted Kyler’s parents, Michael and Tina Leslie, to secure permission to use the image on the cover, they all agreed to keep it a secret until the Guide was published—even Kyler’s little brother kept the secret for nearly two months!

When the Guides arrived, Gipps connected with the family to arrange a special delivery. A group of family and friends planned to gather on the afternoon of Sunday, November 16 at the Petersham Country Store to surprise Kyler with the news.

When he arrived, Gipps was greeted by Kyler’s mother and nearly 20 other people—family, friends, and other notable people from the community including a member of the Fisheries and Wildlife Board and the Petersham Town Clerk, both family friends—all of whom had come to the store to participate in the big surprise.

Everyone was sitting quietly at the back of the store when Kyler and his father arrived. Kyler immediately noticed a friend and ran to see him, but in mid-sprint he realized that a lot of people he knew were there. Then someone from the group said hello and stepped forward holding up a copy of the Guide. Kyler looked at the cover and was stunned. “That’s crazy… what in the world!” he said, wide-eyed.

His family and friends erupted in applause and congratulated him. Kyler wiped away some happy tears and thanked everyone. He remarked that the hat he was wearing was his lucky fishing hat—it was the same hat he’d been wearing when he caught the trophy northern pike. Many hugs and handshakes followed as Kyler made his way from table to table, autographing copies of everyone’s Guide.

“MassWildlife is a lot of things,” said Gipps. “But I think what lies at its core is what I saw that afternoon at the Petersham Country Store. Family and friends gathering to celebrate the enthusiasm and accomplishments of a young sportsman, whose interest in the outdoors was fostered and wholeheartedly supported by his parents, encouraged by the sporting culture in his community, and served by the state’s well-managed fish and wildlife resources.”

Volunteer spotlight: 5 years of bat house monitoring

December is a season of gratitude—and this year, we’re shining a light on MassWildlife’s volunteer bat house monitoring program. Thanks to the dedication of 23 volunteers across Massachusetts, all 34 bat houses at 30 sites were monitored regularly during the summer months in 2025 despite mosquitoes, summer storms, and busy schedules. Over the past five years, a total of 53 volunteers have contributed to the program. Seven volunteers have participated every year since the start of the program, providing consistency and invaluable expertise that guides and strengthen the project.

Massachusetts is home to nine bat species. Several, including the little brown bat and northern long-eared bat, have suffered steep population declines due to white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has devastated bat colonies across North America. Summer roosts are essential for bat survival because they provide females a safe, warm place to raise their pups.

Bats roost in natural areas like tree cavities, and in structures like house attics and barns. Bat houses play an important role in conservation by providing alternative summer roosting habitat when other suitable sites aren’t available. Properly designed and placed bat houses can support colonies of dozens to hundreds of bats, giving them a secure location to rest during the day. By relieving pressure on human structures, bat houses also help reduce conflicts between people and bats.

Results from bat house monitoring are as follows:

- Year 1: 16% occupied, 26% showed potential use

- Year 2: 7% occupied, 10% showed potential use

- Year 3: 10% occupied, 23% showed potential use

- Year 4: 6% occupied, 15% showed potential use

- Year 5: 15% occupied, 9% showed potential use

Although bats can take several years to adopt artificial roosts, the signs of activity we see each summer are promising. Bat house occupancy varies, which is expected since bats naturally rotate between multiple roosts. These results show steady signs of bat activity and a strong likelihood that the houses will continue to be used in the future.

Volunteer bat house monitoring efforts are helping MassWildlife understand species distribution and abundance in Massachusetts, which bat house designs and placements are most successful, and how bat populations respond to changes in habitat availability. Every observation helps build a clearer picture of bat ecology in our state, informing both research and conservation strategies. Thanks again to all of our volunteers for your dedication to bat conservation!

Roche receives Sargent Award for conservation

On November 12, 2025, Mike Roche of Orange received the Francis W. Sargent Conservation Award from the Fisheries and Wildlife Board for his contributions to the sporting community and to the conservation of the Commonwealth’s natural resources. Roche is the 16th recipient of the prestigious award named for the former governor and noted conservationist who directed the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MassWildlife) in 1963–64.

Roche, a lifelong hunter and angler, accepted the award—an engraved crystal obelisk—during a ceremony at MassWildlife’s Field Headquarters in Westborough. Upon receiving the honor, Roche said, “This award is very special because of the people who have gone before me and the example their accomplishments created for everyone who cares about outdoor resources. Being able to meet and work with so many hard-working professionals and passionate volunteers, then seeing the positive results shape the future of conservation in Massachusetts has been a reward that cannot be measured.” Roche also received citations from the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives celebrating his achievement.

The ceremony brought together Fisheries and Wildlife Board members, agency staff, leaders of sporting and conservation organizations, previous Sargent Award recipients, colleagues, friends, and family. MassWildlife Director and event emcee, Mark Tisa, opened the ceremony on a personal note, saying “I’ve had the good fortune to work closely with Mike on many important conservation issues over the years. He’s always been a strong advocate for the sporting community and for ensuring access to the outdoors.”

Roche’s connection to the outdoors in Massachusetts runs deep. Appointed to the Fisheries and Wildlife Board in 1987 at age 37—the youngest member ever—he served the Commonwealth for 35 years, including lengthy terms as Secretary and Vice Chair. His passion for outdoor recreation began in childhood and led him to champion numerous programs across the state. Roche volunteered for 20 years as an instructor with MassWildlife’s Hunter Education program, contributed to Project WILD, and served on the staff of the Massachusetts Junior Conservation Camp, including as Director.

“Mike is a legendary educator and communicator, introducing whole generations to the outdoors in Massachusetts through science, adventure, and hunting and fishing,” said Department of Fish and Game Commissioner Tom O’Shea.

A professional educator, Roche taught at Mahar Regional High School in Orange from 1975 until his retirement in 2011. During a four-year leave, he served as Regional Director for Ducks Unlimited in Massachusetts. At Mahar, he taught social science, forestry, and wildlife management electives, and advised the Mahar Fish‘N Game Club—believed to be the oldest high school fish and game club in the state.

Beyond teaching, Roche is known as an accomplished outdoor writer, producing the weekly “Sportsman’s Corner” column for the Athol Daily News since 1984. He remains active in the New England Outdoor Writers’ Association and the Outdoor Writers of America.

When presenting the award, Fisheries and Wildlife Board Chair Emma Ellsworth praised Roche’s passion for teaching and love of the outdoors. “His ability to connect people to nature has had an extraordinary ripple effect—touching students, sportsmen and women, and the broader community. It’s a privilege to recognize his decades of dedication with the Sargent Award.”

Avoid decorating with invasive plants

During the holiday season, many people use plants to decorate their homes or businesses. If you wish to use plants in your decorations, be sure to select native species such as native pines, spruces, hemlock, American holly, mountain laurel, fir, or winterberry holly.

Avoid exotic, invasive plants like Asiatic bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) and multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). These plants may have attractive berries, but they can cause severe damage to native plants, shrubs, and trees. Invasive plants can spread quickly in open fields, forests, wetlands, meadows, and backyards, crowding out native plants that provide valuable wildlife habitat. Asiatic bittersweet can even kill mature trees. Cutting and moving these invasive plants to make wreaths or garland can spread their seeds even more. Birds may also feed on the fruits hung for decoration and further spread the digested but still-viable seeds. Both plants are extremely difficult to control; when cut, the remaining plant segment in the ground will re-sprout and grow quickly. It is illegal to import or sell Asiatic bittersweet and multiflora rose in any form (plants or cuttings) in Massachusetts.

Get tips to identify Asiatic bittersweet and multiflora rose below or click here to learn more about invasive plants in Massachusetts.

Asiatic bittersweet

Identification: A climbing deciduous, woody vine that can grow up to 60 feet long and up to 6 inches in diameter. It can also grow along the ground spreading orange-colored roots. Young stems are brown with warty lenticels (raised pores); bark of older plants appears gray. New twig growth is smooth and green. Leaves are rounded and are narrower at the base. Small greenish flowers bloom from May to June. Yellow-orange capsules are produced from July to October. Later in the fall, the seed covering splits open to reveal red-orange seeds.

Threat: Asiatic bittersweet grows fast and wraps around nearby shrubs or trees. Native woody plants can be shaded out, strangled, or uprooted. It can reproduce by seed or through root suckers.

Multiflora rose

Identification: A deciduous shrub with arching and scrambling stems that may grow up to 10–15 feet tall. The stems are red to green with scattered, broad-based prickles. Each leaf has 5–11 elliptical leaflets with sharply serrated edges. After the flowers fade in late summer, rose hips (resembling leathery red berries) are left on the plant and remain throughout the winter.

Threat: Multiflora rose grows in dense thickets and quickly outcompetes other plants. It can completely dominate abandoned fields or pastures. Each plant can produce half a million seeds and these may remain viable in the soil for up to 20 years.

Who benefits from habitat restoration?

Over the past year, MassWildlife implemented restoration work on ~2,700 acres of habitat within Wildlife Management Areas across the Commonwealth. When habitats are restored, everything starts to thrive—from the smallest wildflower to the local economy; even you can benefit from a healthy habitat.

At first glance, habitat restoration might look a little messy—selective tree cuts, controlled burns, herbicide treatments—but these actions are carefully planned by MassWildlife Biologists to bring about specific habitat conditions. Think of it like a house renovation. Walls are torn down, fixtures are removed, and the house is rebuilt to be stronger, safer, and more functional. Sometimes habitats need a reset to let natural processes become established and allow native plants to flourish.

Wildlife wins

Healthy habitats mean healthier plants and animals. Restored ecosystems provided cleaner air and water, as well as crucial shelter and food sources. Over time, this invites more species back, including both common and rare species that depend on specific native plants or landscape features to survive. These places are then better positioned to adapt to the changing climate and withstand other stressors. Research backs this up: biodiversity increases over time in restored areas.

Foragers rejoice

Think about the flavor of the land: blueberries , beach plums, wild raspberries, elderberries, and mushrooms, like hen-of-the-woods, thrive in properly managed habitats. In Massachusetts, chicken-of-the-woods often appears in woodlands after prescribed fire has been conducted. These wild foods can be bountiful in restored ecosystems, inviting everyone from backyard foragers to local chefs to enjoy.

Hunters, anglers, and outdoor enthusiasts

Forest management activities can boost hunting opportunities. Young forest habitats support ruffed grouse, woodcock, and wild turkey at various stages of their life cycle. In particular, edge habitat—the intersection of open and forested areas—attracts deer and black bears.

In the same manner, restored rivers and streams benefit anglers. Removing dams and resizing culverts open pathways for migratory fish, like trout and herring. With healthier fish populations upstream, new places may pop up as the ‘best local fishing spot’.

A feast for the eyes and ears

Birdwatchers will tell you: you can hear a healthy habitat. Restored habitats often attract a more diverse collection of bird species singing in forests and grasslands. Hikers and wildlife photographers benefit too, with access to landscapes full of life, color, and diversity. With restored areas often come new views that were previously blocked by overgrowth.

Jobs and local economies

Restoration isn’t just good for wildlife, it’s good for people’s livelihoods too! Farmers benefit from ecological services like more pollinators, natural pest control, and cleaner water. Foresters benefit from healthier, more sustainable woodlands. Restored habitats encourage eco-tourism which puts dollars back into local communities.

And yes, everyone else too

Even if you never leave the city, restoration helps you. Forests and wetlands filter drinking water, store carbon, and reduce air pollution. In urban areas, green spaces cool down overheated neighborhoods and protect against flooding. Healthier habitats reduce erosion, buffer storm surges, and even raise nearby property values.

So, who benefits from habitat restoration?

Birds, berries, bears—and you.

Give a gift on the wild side!

Now is the time of year to think about the outdoor or wildlife enthusiast on your holiday list—consider the following wildlife-related gifts available from MassWildlife.

MassWildlife publications

- A 2-year subscription to Massachusetts Wildlife magazine ($10) delivers eight full-color issues of the Commonwealth’s best wildlife publication. The magazine is packed with award-winning articles and photos on the environment, conservation, fishing, hunting, natural history, and just about everything related to the outdoors in Massachusetts. Subscribe by mail or online.

- MassWildlife offers Massachusetts-specific field guides including Guides to Amphibians and Reptiles and Animals of Vernal Pools. Order MassWildlife publications.

Charitable donations

For the person who has everything, make a donation in his or her name to support one of the following:

- MassWildlife's Hunters Share the Harvest Program provides an opportunity for hunters to donate venison to Massachusetts residents in need. Anyone can help financially support the program to cover the cost of meat processing and packaging. A donation of $25 will provide about 50 servings of meat for families in need!

- To donate:

Use MassFishHunt to donate online.

Or send the honoree's name with a check payable to Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Please write "HSH Program" in the memo.

Mail to: MassWildlife, Attn: Hunters Share the Harvest Program, 1 Rabbit Hill Rd., Westborough, MA 01581

- To donate:

- The Wildlands Fund is dedicated to acquiring and conserving important wildlife habitat open to wildlife-related recreation.

- To donate:

Use MassFishHunt to donate online.

Send the honoree’s name with a check payable to Comm. of Mass–Wildlands Fund. Mail to: MassWildlife, 1 Rabbit Hill Rd., Westborough, MA 01581

- To donate:

- The Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Fund supports protection of the 400+ animals and plants listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

- To donate:

Use MassFishHunt to donate online.

Or send the honoree’s name with a check payable to Comm. of MA–NHESP. Mail to: MassWildlife, NHESP, 1 Rabbit Hill Rd., Westborough, MA 01581

- To donate:

Contact

Online

| Date published: | December 5, 2024 |

|---|