- Scientific name: Alnus alnobetula ssp. crispa (Aiton) Raus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Mountain Alder leaves and immature cones. Photo credit: Bruce Sorrie

Mountain alder (Alnus alnobetula ssp. crispa) is a northern, colonial shrub reaching 3 m (12 ft) in height. It has simple, alternate, sharply toothed leaves with 6-9 main veins on both sides. The ovate or heart-shaped leaves are 4-9 cm (1.5-3 in) in length and 2-2.5 cm (0.8-1 in) in width. The leaves are borne on short branch spurs and are frequently shiny and resinous when young. In Massachusetts, mountain alder usually grows on exposed ledges, boulders, and cobble bars along major rivers in the western part of the state. It can be surveyed throughout most of the year.

Mountain alder’s winter buds are sessile on the stem unlike those of other native alders in Massachusetts and have 3-5 overlapping scales. The buds are often reddish. It has male and female flowers borne on separate catkins, which develop in spring at the same time as the expanding leaves. In spring, clusters of drooping, pollen-bearing male catkins reach a length of 5-8 centimeters. Female catkin clusters (2-10 in number) have two to three leaves at the base and develop into woody, cone-like structures following fertilization in May and June. Mountain alder bark is typically smooth. The young branches are resinous, with scattered lenticels and a three-sided pith.

Mountain alder flowering and leaf expansion. Photo credit: Bruce Sorrie

Two alder species in Massachusetts, speckled alder (Alnus incana) and smooth alder (Alnus serrulata) closely resemble mountain alder. Speckled alder frequently occurs in association with mountain alder in river edge habitats. Features distinguishing mountain alder include its sessile, overlapping winter buds (the other alders have stalked buds with 2 or 3 even scales); its broadly-winged fruits (both speckled and smooth alder have narrow-margined fruits); the maturation of its staminate catkins with the expanding leaves (in speckled and smooth alders, the male catkins develop before the leaves open); and the leaves are borne on short branch spurs (the other alders lack this structure). All three alder species have sharply-toothed leaves which are generally ovate in form. Mountain alder leaves are shinier, stickier, and have fewer main veins (6-9 as opposed to 8-14) than the other alders.

One introduced and invasive species of alder, European or black alder (Alnus glutinosa), could also be confused with mountain alder. European alder has 5 to 8 veins on each side of leaf and their seeds are also broadly winged similar to mountain alder. However, like the other two above species, its buds are stalked unlike the sessile buds of mountain alder. The fully expanded leaves of black alder are distinctive as the tips of the leaves are indented, rather than having a pointed tip.

Life cycle and behavior

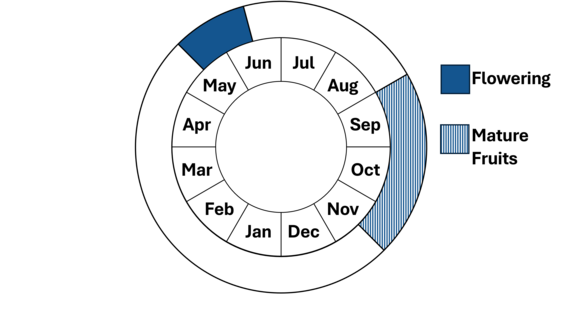

Mountain alder is a colonial perennial shrub. Its leaves expand at the same time as the flowers, with cones and seeds maturing in mid-summer to early fall.

Population status

Mountain alder buds, leaf and flower. Photo credit: Peter Grima

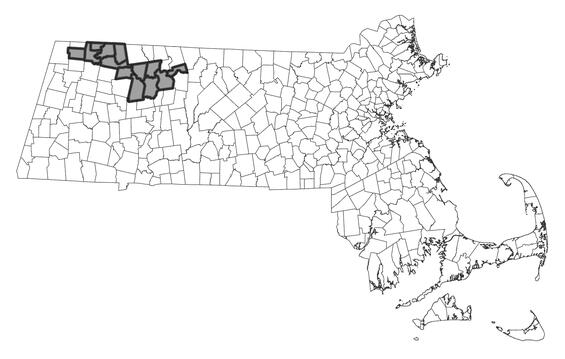

Mountain alder is currently listed as special concern in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. Mountain alder is rare in Massachusetts because it is nearing the southern limit of its range, and there is limited cool, open, montane, or river shore habitat available in Massachusetts. There are 21 current mountain alder occurrences in Massachusetts which have been observed since 2000. Most of these populations occur along the Deerfield River in Berkshire and Franklin counties with a few additional populations in both counties. Mountain alder numbers at these stations range from several to 100 or more plants. Two other occurrences have not been observed since 2000.

Distribution and abundance

Mountain alder is a circumboreal species. In North America, it ranges from Labrador and Newfoundland west to Alberta and south to Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, and Minnesota. There are disjunct populations in western Pennsylvania and on Roan Mountain straddling the North Carolina – Tennessee border. Western Massachusetts is the southernmost point of mountain alder in New England. It is more widely distributed in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, though it is considered Vulnerable in Vermont and New York.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Mountain alder in Massachusetts occurs in several habitat types which combine open, exposed areas and cool local temperatures. The most common habitats are exposed ledges, boulders, and cobble bars on the edges of the Connecticut and Deerfield Rivers. Many of these high-energy river shores are influenced by seasonal flooding. Other habitats include a railroad cut and a road cut in the vicinity of the Deerfield River, and one upland site on an exposed summit and ridgeline (c. 1700 feet in elevation) on a mountain in Franklin County. Associated species include red maple (Acer rubrum), silver maple (Acer saccharinum), sugar maple (A. saccharum), white ash (Fraxinus americana), speckled alder (Alnus incana), willow species (Salix spp.), meadowsweet (Spiraea latifolia), red-berried elder (Sambucus racemosa), broom sedge (Carex scoparia), spotted Joe-pye-weed (Eutrochium maculatum), swamp candles (Lysimachia terrestris), American royal fern (Osmunda spectabilis), tall meadow-rue (Thalictrum pubescens), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris) and golden Alexanders (Zizia aurea).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Mature cones of the Mountain alder. Photo credit: Peter Grima

Mountain alder is a disturbance-adapted, relatively hardy species. Threats to its persistence in Massachusetts include alteration of disturbance regimes, conditions keeping its habitat open, or competition with the invasive exotic Japanese knotweed, also known as itadori (Reynoutria japonica). Higher rainfall events resulting from climate change may impact the current disturbance regime along the banks of Deerfield River and its tributaries. It is not known if that change will impact this rare plant.

Conservation

As for many rare species, the exact needs for management of mountain alder are not known. The following comments are based primarily on observations in Massachusetts. Mountain alder grows best on exposed rock on the edges of large rivers. It can tolerate periodic inundation. Most of the populations occur along the Deerfield River, which is subject to periodic releases from the Bear Swamp pump storage station. The Deerfield River populations do not appear to be affected by the fluctuating water levels; in fact, the flooding is likely beneficial in that the physical disturbance of the flooding (and ice scour) halts succession at these sites. The populations in the railroad and road cuts could be affected by maintenance activities or roadbed expansion.

References

Haines, Arthur. Flora Novae Angliae. New England Wild Flower Society, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. 2011.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 1/17/2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Retrieved 17 January 2025."

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D’Amato. A Regional Synthesis of Climate Data to Inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast, U.S. U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86 2024

Symonds, George W.D. The Shrub Identification Book. William Morrow a& company, New York, New York. 1963

Contact

| Date published: | March 6, 2025 |

|---|