- Scientific name: Calamagrostis inexpansa Gray

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

New England northern reed grass is a member of the grass family (Poaceae) that occurs in a variety of moist, open habitats. This subspecies grows to a height of 0.3-1.5 m (1-5 ft), with long, narrow leaves that are flat, often stiff, and rough to the touch. The spikelike, dense flower clusters are typically 6-20 cm (2.4-7.9 in) long. This perennial species produces rhizomes, and may be found growing as solitary stems or forming close clusters.

Identification of New England northern reed grass requires use of a technical manual and a hand lens or microscope. In grasses, the basic flowering unit is a spikelet, which consists of one or more flowers (florets) that are typically subtended by a pair of bracts (glumes). The stamens and pistil are found between a pair of bracts called the lemma and palea. In Calamagrostis stricta, the glumes are longer than the lemma, and the lemma has a stiff bristle (awn) at its tip that may be twisted and bent, or straight, and is attached at or below the middle of the lemma. The rachilla, the axis of the spikelet, is 0.6-1 mm (0.02-0.04 in) long, and is covered with hair throughout its length. In C. stricta spp. inexpansa, the glumes are thick and opaque, averaging 3-6 mm (0.12-0.24 in) long. The callus, a hard protuberance at the base of the lemma, is coated in white hairs that are two-thirds to fully as long as the lemma and may appear as two lateral tufts.

Calamagrostis stricta spp. stricta has leaf blades that are in-rolled, and rough only at the margins and apex. The glumes of this subspecies are translucent near the margins and tip. In C. pickeringii, the awn is attached near the base of the lemma and is always twisted and bent. The callus hairs of C. pickeringii are only 20-30% the length of the lemma. C. cinnoides has longer spikelets than C. stricta ssp. inexpansa, with awns attached above the middle of the lemmas, and rachillas that are hairy only at the apex. In C. epigejos, the rachilla is not prolonged as a bristle. In C. canadensis, the inflorescence is loose and open rather than compact, and the rachilla is only 0.1-0.3 mm long. New England northern reed grass may also be confused with members of other genera, and it is important to use a technical key for proper identification.

Life cycle and behavior

This is a perennial herbaceous grass.

Population status

New England northern reed grass is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as endangered. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale, and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. New England northern reed grass is known in Massachusetts from two isolated populations in Worcester and Berkshire Counties. The Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program database has 3 records from 2 counties: Berkshire and Worcester. All 3 records have been observed within the last 25 years.

Distribution and abundance

New England northern reed grass occurs throughout the northern United States and in northern Canada and Alaska, south to West Virginia, and west to Arizona and California. It is moderately common along the shores of the western Great Lakes and in isolated stations in the northern Appalachians, but uncommon or rare in New England and Maritime Canada.

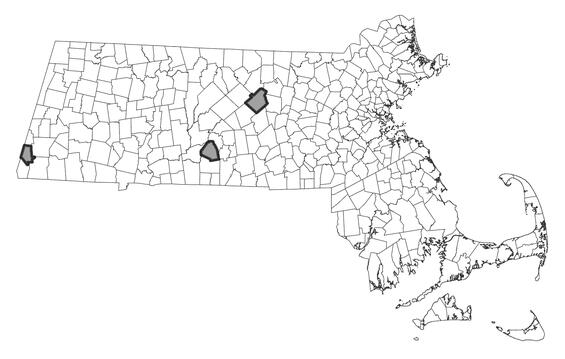

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

New England northern reed grass colonizes open to lightly forested habitats relatively free from interspecific competition, including wet meadows, marshes, damp woods, sandy shores, bogs, riverbanks, and sandy stream banks below the flood line. It may also be found in alpine areas, fire-disturbed summits, and cool, damp cliff faces at high altitudes. In Massachusetts, this subspecies is known from a small bald among dry, rocky, open woods, and on a rock outcrop in mesic, oak-dominated forest. Associated species may include hickory (Carya spp.), bear oak (Quercus ilicifolia), black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), and ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Extant populations of New England northern reed grass may be threatened by increased shading from woody vegetation in the absence of disturbance. Maintenance or restoration of natural fire regimes may help protect this species from habitat loss. Sites that support this species should be protected from heavy recreational use, and from dramatic changes in light or moisture conditions. Invasive species should be monitored at sites supporting this species; if aggressive native or non-native species are out-competing New England northern reed grass, a plan should be developed, in consultation with the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, to remove the competitors. All active management of state listed plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Conservation

As this plant is under-surveyed, a serious effort should be made to conduct de novo surveys in areas where this is likely to occur or resurveys where records are over 25 years old.

At two known sites, the species is found in lightly forested glades in areas where wildfire was likely to occur over time. Prescribed fire should be conducted at these sites to see if, as expected, the populations would become more robust.

The exact ecological needs of this species are not well understood. As this plant is under-surveyed, standard information is needed such as lists of associated species, comments on habitat quality and threats, and assessments of soil conditions and phenology. Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a greenhouse or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, this strategy could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Gleason, H.A., and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, 2nd edition. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY.

Greene, C.W. 1980. The Systematics of Calamagrostis (Gramineae) in eastern North America. PhD. Dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 5/12/2025

Contact

| Date published: | May 15, 2025 |

|---|