- Scientific name: Malaclemys terrapin

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Adult female northern diamond-backed terrapin.

Diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) is Massachusetts’ only turtle found predominately in salt marshes and estuaries. The terrapin is an iconic and characteristic species of these environments, where it is usually the only species of turtle (although snapping turtles [Chelydra serpentina] are locally common in the upper part of brackish estuaries). Although they are not found in freshwater habitats, the terrapin is in the family Emydidae, which includes mostly freshwater species, and is closely related to the map turtles (Graptemys spp.). The carapace is frequently discolored by algae or silt, though, so the pattern is not always clearly visible, but the terrapin’s carapace is variable in color, and can appear gray to light brown. Some individuals also have black, orange, green, or tan markings on the shell. The carapace is oval to slightly egg-shaped. Terrapins have keeled carapaces with prominent bumps on the vertebral scutes. Skin on the head and limbs is gray to white with small dark spots. Terrapins have large heads with powerful musculature, and their jaws are usually light-colored. Males and females are dimorphic (i.e., shaped differently): females are larger than males, reaching lengths of 15-23 cm (6-9 in), while males are usually 10-15 cm (4-6 in) in shell length. Hatchling terrapins are mostly gray but otherwise are similar in appearance to adults, and measure approximately 2.6 cm (1 in) long. Usually, only nesting females are observed on land. More often, a keen observer will only spot the terrapins’ heads protruding from the surface of a calm bay.

Similar species

Terrapins are the turtle species found most commonly in Massachusetts salt marshes, although snapping turtles are frequently found in some estuarine rivers. To a much lesser extent, painted turtles (Chrysemys picta), spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata), and/or eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina) may be found in salt marsh habitats, usually near sources of fresh water. Researchers in Massachusetts have even observed northern red-bellied cooters (Pseudemys rubriventris) in areas occupied by terrapins. Terrapins could be misidentified as a small sea turtle because of their occurrence in brackish waters near the ocean, but terrapins lack the flipper-like front limbs of the hard-shelled or cheloniid sea turtles. When viewed in hand or up-close, the terrapin’s whitish-gray skin is unique. The terrapin’s strong preference for tidal bays, creeks, and marshes usually helps to distinguish them from other turtle species in the Commonwealth.

Life cycle and behavior

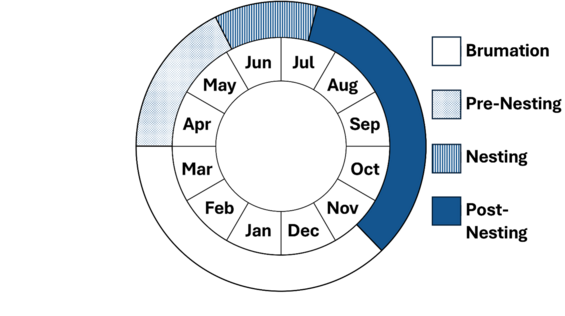

Diamondback terrapins have a seasonal and daily life cycle that is tied to the tidal cycles and seasonal changes of their estuarine and saltmarsh habitats. Terrapins spend the winter months (approximately late-October to early-April) in a state of dormancy called “brumation”, submerged in the muddy bottoms of harbors, tidal bays, tidal creeks, and salt marsh channels. In the spring—as the water warms dramatically in shallow and enclosed bays—terrapins emerge from brumation and congregate in bays and inlets and tidal creeks to court and mate. Courtship and mating aggregations range from a few individuals to over 100. Beginning in June, females move toward their preferred nesting areas, which can sometimes be up to 0.4 km (0.25 mi). Terrapins prefer to nest in dry, sandy, cleared areas well above the high-tide line (these important nesting areas are occasionally inundated by significant storm events, a phenomenon likely to increase). Like most turtle species in Massachusetts (except the bog turtle, Glyptemys muhlenbergii, and the wood turtle, Glyptemys insculpta) diamondback terrapin hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the nest during incubation. Eggs incubated below 28˚C (82˚F) are more likely to become male, while eggs incubated at temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) usually develop into females. Nest incubation periods in Massachusetts range from 59-116 days, depending on temperature. After hatching, young turtles may delay their egress from for several days, and terrapin hatchlings are known to remain on land for extended periods following emergence (they do not move directly to the marsh). Females reach sexual maturity between 8-10 years of age, and males mature earlier. The average lifespan of a diamondback terrapin is probably at least 40 years, though some individuals may live considerably longer. Terrapins are opportunistic omnivores, and they forage in aquatic habitats for mostly invertebrate prey. Common food items include crabs, crustaceans, mollusks, and insects; fish is probably taken as carrion. Terrapins’ foraging movements are tied to the tidal cycle: individual turtles access areas of low marsh, shallow channels, and ditches during high tide.

Adult female diamondback terrapin foraging in low marsh at high tide, showing characteristic whitish skin with black spots.

Distribution and abundance

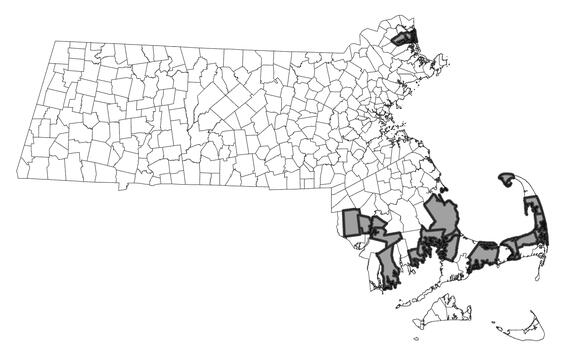

The subspecies of terrapin found in Massachusetts is the northern diamond-backed terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin), which ranges from Cape Cod, Massachusetts to the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Other subspecies of terrapin are found along the Atlantic coast to southern Texas. Notable areas with large populations include Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay. In Massachusetts, terrapin populations are limited to Cape Cod, Buzzards Bay, and the lower Taunton River watershed, although individuals have been found as far north as Plum Island.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Diamondback terrapins are iconic inhabitants of the brackish-water ecosystems in Massachusetts. They are found almost entirely in brackish embayments, estuarine and tidal creeks, salt marshes, and brackish harbors, although their nesting movements may take them into less typical aquatic habitats. These estuarine and salt marsh environments have varying salinities that vary with the tide, and the species is tolerant of varied and varying salinity levels. Terrapins are exceptionally well-adapted to fluctuating tidal conditions. Depending on the season and the tidal cycle, terrapins can be found both in the high marsh and low marsh zones, as well as in open water such as harbors, and they are frequently seen near fishing access areas. Across their large (but linear) range from New England to Texas, terrapins occupy a range of brackish-water habitats. Populations in southern Florida are uniquely adapted to red mangrove ecosystems. Terrapins nest exclusively in open-canopy, upland areas of sand or sandy loam, including interdunal areas, elevated beaches, roadsides, clearings in sparse pitch pine (Pinus rigida) forests, construction sites, gardens, and yards, as well as purposefully-constructed “turtle gardens.”

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Typical estuarine habitats of the diamondback terrapin Massachusetts.

Threats

Diamondback terrapins declined precipitously in the early 1900s because of targeted collection for food markets. The historical overharvesting of terrapins for gourmet consumption nearly led to their extinction. Fortunately, terrapins are no longer harvested indiscriminately in New England, but they still face ongoing threats to population persistence. The most obvious and pressing of these are the risks associated with climate change: sea level rise and large storms pose existential threats to terrapins, their salt marsh habitats, and many low-lying nesting areas. Rising sea levels inundate nesting habitats, drown nests and reduce the availability of suitable nesting sites, making female terrapins travel farther distances (potentially crossing more roads) to access nesting areas. But like freshwater turtles in Massachusetts, terrapins are also negatively affected by the reduction and alteration of their salt marsh habitat due to various human activities. Coastal development and urbanization continue to encroach upon suitable aquatic habitats, limiting safe nesting opportunities and the ability of salt marshes to migrate inland with rising sea levels. "Armoring" of the coastline reduces habitat quality while preventing terrapins from accessing upland nesting areas, and displaces shoreline erosion during large storms to more natural areas. And as with other emydid turtles in Massachusetts, roadkill is a significant threat to terrapins, because it disproportionately affects nesting females crossing roads to reach nesting habitats. Wild terrapins occasionally show healed carapace fractures from automobile strikes (although some of these injuries may be from boat propellors). Diamondback terrapins are still occasionally collected in Massachusetts for both pet markets and for personal consumption. Terrapins can become entangled and trapped in abandoned crab traps and discarded fishing nets. Trapped terrapins will drown if they cannot access air to breathe. Terrapins are also hooked on fishing lines.

Representative nesting habitats of the diamondback terrapin Massachusetts.

Conservation and management

Terrapins are slowly recovering from decades of systematic harvest, but they need continued management and conservation efforts to persist and thrive in the context of rising sea levels and coastal development. For example, it is important to protect existing salt marshes from development and other destructive activities while also restoring degraded salt marshes. Removing anthropogenic tidal restrictions will facilitate the inland migration of salt marshes. As saltmarsh restoration projects gain momentum, it’s important to consider the unique biology of terrapins by minimizing interactions with roads and providing suitable nesting areas.

It's also important to reduce the number of terrapins killed on roads. MassWildlife should continue to work proactively with MassDOT to review bridge replacement projects in terrapin habitat to make sure that terrapins are excluded from the roadway surface by permanent barrier fencing. In some areas with high roadkill rates, it may be appropriate to use terrapin-crossing signs, barrier fencing, and/or under-road passage structures. Some local roads could be seasonally closed in late June and early July to reduce mortality. Some populations would benefit from the protection of nests and/or headstarting to promote population recruitment.

Six-sided traps for blue crabs are now illegal in Massachusetts to protect terrapins and support their recovery. It’s important to enforce crab trap restrictions and remove abandoned traps to prevent terrapins from entering and drowning. Ongoing research and monitoring of terrapin populations are important for informing management decisions and assessing the effectiveness of conservation efforts, including (a) standardized population surveys to estimate abundance and distribution and to detect changes over time; (b) monitoring nesting sites, key predators, and nest survival rates; (c) studying terrapin movements and habitat use through telemetry and other tracking methods, and (d) investigating the influence of habitat loss, road mortality, and bycatch on terrapin population viability.

This adult female terrapin shows signs of a healed injury from an earlier boat or car strike.

References

Brennessel, B. 2006. Diamonds in the Marsh: A Natural History of the Diamondback Terrapin. University Press of New England, Lebanon.

Egger, S., and the Diamondback Terrapin Working Group. 2016. The Northern Diamondback Terrapin in the Northeastern United States: A regional conservation strategy.

Levasseur, P., S. Sterrett, and C. Sutherland. 2019. Visual head counts: a promising method for efficient monitoring of Diamondback Terrapins. Diversity 11:101.

Levasseur, P., M.T. Jones, B. Brennessel, R. Prescott, M. Faherty, and C. Sutherland. 2022. Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) density and space use in dynamic tidal systems: Novel insights from spatial capture–recapture. Journal of Herpetology 56(2), pp.180–190.

Contact

| Date published: | April 17, 2025 |

|---|