- Scientific name: Pseudemys rubriventris pop.1

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Endangered (US Endangered Species Act), Massachusetts population only

Description

The northern red-bellied cooter (Pseudemys rubriventris) is one of the largest freshwater turtles native to Massachusetts, second only the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Adult “redbellies” can grow to a shell length of 25 to 35 cm (10 to 13.5 in) and weigh up to 5.8 kg (12.7 lb). The carapace or upper shell of an adult red-bellied cooter can range from black to brown, often with reddish vertical bars on the scutes. Some males will develop an unusual marbled-red coloration, and some individuals may become melanistic (dark-pigmented). The plastron or bottom shell shows differs between males and females: males usually have a pale pink plastron with gray mottling, while females have a pink or rose-colored plastron with gray borders along the edges of the shell plates. The head, limbs, and tail of the northern red-bellied cooter are generally black with ivory or yellow stripes. Redbellies have a distinctive, arrow-shaped stripe that run along the throat and neck. Like painted turtles (Chrysemys picta), but unlike other clades within the Pseudemys genus, the upper jaw has a noticeable ‘cusp’ or notch. Males and females differ not in their plastron color: males have larger and longer tails compared to females, longer claws on their front feet.Upon hatching, northern red-bellied cooters are about 25 mm (1 in) in length and have a more circular shell. Their carapace is greenish with yellowish markings.

Similar species: No other basking turtle in Massachusetts is as large as the northern red-bellied cooter. Redbellies are most often confused with either painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) or introduced (non-native) red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans). Both the painted turtle and the northern red-bellied cooter have yellow markings on their head and neck, and their plastrons can have an orange cast. The red-bellied cooter, however, is much larger (as an adult) and lacks a pronounced yellow spot behind the eye that is characteristic of the painted turtle. Also, the carapace of the red-bellied cooter is flattened or slightly depressed on top, and the scutes on the carapace alternate between vertebral and costal, while the costal and vertebral scutes tend to align in Massachusetts populations painted turtle. The plastron of the red-bellied cooter is rose-colored, coral-red, or pink, with gray markings, while the plastron of the painted turtle in eastern Massachusetts (where the two species co-occur) is usually yellow. The red-eared slider—not native to Massachusetts—has become established in some ponds in Plymouth County, where it co-occurs with native redbellies. However, it can be distinguished from redbellies by a red stripe behind its eye and black markings on its plastron. A related subspecies of slider, the yellow-bellied slider (Trachemys scripta scripta), can be told from the redbelly by a serrated rear carapace margin. Unfortunately (due to an extensive pet trade) a number of other non-native relatives of the redbelly (subfamily Deirochelyinae) occur locally in Massachusetts. These include other species of cooters, such as the river cooter (Pseudemys concinna), the Florida red-bellied cooter (Pseudemys nelsoni), and the Florida cooter (Pseudemys floridana). Other introduced (but uncommon) species include several species of map turtles (Graptemys spp.).

Life cycle and behavior

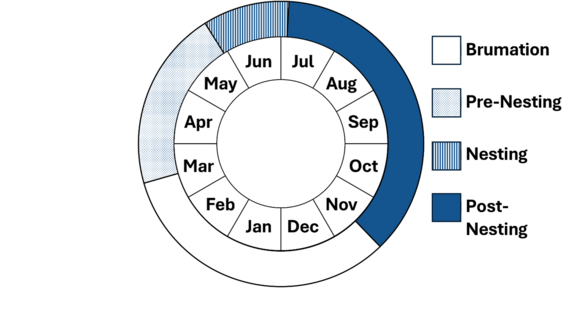

Northern red-bellied cooters are active in Massachusetts from late March to October. They spend the winter underwater in a state of inactivity called “brumation”, typically at depths of 1–3 m (3.3 to 9.8 feet). During the active season from April to October, redbellies almost exclusively aquatic, and spend most of their time in the water. Redbellies bask frequently on logs, rocks, vegetation mats, and even anthropogenic rafts and docks. Basking is important for this southern-adapted species at the northern edge of its range, because it allows them to maintain an optimal body temperature and reducing the risk of infection. Although they mostly aquatic year-round, individuals move regularly between nearby ponds. Studies have shown that redbellies readily move between ponds less than 40 m (130 ft) apart. Longer-distance movements are less common. Redbellies mate in the spring. Female redbellies leave the water to nest in June and early June, selecting an open, sandy cleared area near water such as powerline corridors, cranberry operations, yards, gravel pits, and roadsides. Females dig a flask-shaped nest about 10 cm (4") deep and lay about 10–20 eggs. The incubation period lasts 73 to 80 days. Like most turtles in Massachusetts sex of the hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the nest site; warmer temperatures produce females, while cooler temperatures produce males. Hatchlings emerge from late August through October, but they rarely will overwinter in the nest. As adults, red-bellied cooters feed primarily on aquatic vegetation such as milfoil, bladderworts, arrowheads, and water-shield, but when young they may also consume crayfish and other invertebrates. Adults also opportunistically eat snails, fish, tadpoles, and crayfish; interestingly, freshwater turtle remains have been found in their scat (likely from scavenging on carrion). Female northern red-bellied cooters are believed to reach maturity around 13 years of age, which is later than males. However, headstarted females, due to their accelerated growth in captivity, may begin nesting much earlier. Redbellies have a long lifespan, potentially exceeding 60 years in the wild, with a generation time likely over 25 years.

Population status

The northern red-bellied cooter had dwindled to fewer than 300 individuals at the time the species was listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in May 1980. The species was known only from Plymouth County at the time, and primarily the towns of Plymouth and Carver. Today, the species’ total population size is at least 10 times its numbers in 1980 and the species is known to occur in at least 43 separate pond complexes and river systems. MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program has coordinated a “headstart” program for the red-bellied cooter since 1984. As of 2024, over 5,000 headstarted turtles have been released at more than 30 sites. This program involves collecting hatchlings from natural nests in August and raising them in captivity for their first year. By the time of their release in May, these “headstarted” turtles are the size of wild 3-year-olds, increasing their survival rates.

Distribution

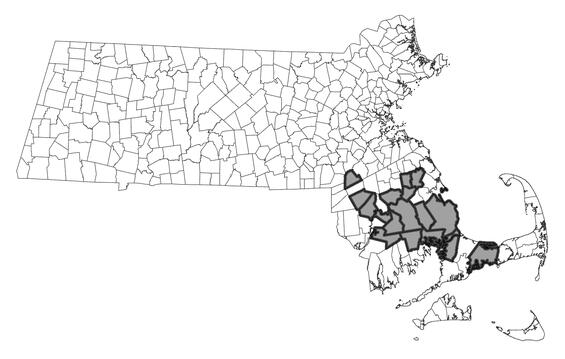

Massachusetts populations of the northern red-bellied cooter are isolated from the nearest native populations in New Jersey by about 320 km (200 mi). There are likely introduced populations of redbellies in New York. Massachusetts populations were long classified as a distinct subspecies, the Plymouth redbelly turtle (Pseudemys rubriventris bangsi), but no subspecies are currently recognized. The northern red-bellied cooter is distributed from the coastal plain of New Jersey south to North Carolina's Outer Banks, reaching inland to West Virginia in the Potomac watershed. In Massachusetts, the northern red-bellied cooter is found mostly within Plymouth and Bristol Counties. Smaller populations exist in Norfolk and Barnstable Counties (specifically west of the Cape Cod Canal). There are enigmatic reports of redbellies from the Ipswich River watershed, where they were reported in the 1980s and again in 2023–2024. Archaeological evidence suggests that the species was more widespread in Massachusetts during warmer periods 1,000–6,000 years ago, following the last glaciation. Subfossil remains have been found in several locations, including Ipswich, Wayland, Concord, Westborough, and Martha’s Vineyard.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The northern red-bellied cooter in Massachusetts inhabits freshwater ponds and rivers with (a) abundant aquatic vegetation, (b) suitable basking sites; (c) underwater cover; (d) suitable nesting areas adjacent to the waterbody. Historically, most documented occurrences of the red-bellied cooter were in naturally-formed coastal plain ponds. Their habitat has expanded to include manmade reservoirs, cranberry ponds, larger lakes, and rivers. This expansion is due in large part to MassWildlife’s 40-year headstart program. Historically, natural and human-caused fires certainly played a role in creating and maintaining open, sandy areas near ponds suitable for nesting. With decades of fire suppression, the resulting canopy closure and increased undergrowth has reduced the availability and quality of natural nesting sites. Redbellies have adapted by nesting in developed areas, but with increased risks from human activity and predators.

Habitats: Coastal plain ponds, deep drainage lakes and ponds

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Red-bellied cooters—despite being fairly adaptable and “at home” in a wide range of aquatic habitats—face numerous threats at the northern edge of their range. A primary threat, as it is for most Massachusetts turtles, is the loss of upland habitat adjacent to suitable waterbodies and resulting loss of connectivity to other populations. Roadkill and loss of connectivity are of concern throughout the redbelly’s range—on small residential roads, but also on larger highways like US-44 and US-3. Predators are also a key factor: hatchling mortality is high in many ponds due to depredation by skunks, raccoons, bullfrogs, water snakes, wading birds, and bass. Redbellies are probably also affected by introduced and invasive plant species, eutrophication of coastal wetlands, motorboat strikes, and diseases, and competition from introduced turtles such as the red-eared slider. Redbellies’ late maturation age and low rate of reproduction compound these threats, making it challenging for populations to recover from losses..

Conservation

Significant progress has been made toward the recovery and long-term survival of the northern red-bellied cooter in Massachusetts as a result of a 40-year headstarting program, but the species requires continued conservation attention. Redbellies will benefit from (a) targeted habitat management to improve nesting areas and basking opportunities; (b) outreach to landowners, especially in Plymouth and Bristol County; (c) continuation of MassWildlife’s headstart program in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and statewide partners; (d) interagency cooperation to improve habitat in the southeastern pine barrens landscapes; (e) targeted acquisition of upland habitats near important waterbodies, with special attention on the original pond complex where redbellies were first discovered.

It is important to critically evaluate the effectiveness of the headstart program. A recent study by MassWildlife and the University of Massachusetts Amherst found high annual survivorship rates (over 95% in some ponds) and widespread reproduction and recruitment in headstarted populations. Research is ongoing, aiming to further understand the species’ status, distribution, and management needs.

References

Amaral, M. 1994. Plymouth Red-bellied Cooter Recovery Plan. Northeast Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Hadley, Massachusetts, 39 pp.

Babcock, H.L. 1919. The Turtles of New England. Mem. Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 8(3): 323–431.

Babcock, H.L. 1916. An addition to the chelonian fauna of Massachusetts. Copeia 38: 95–98

Babcock, H.L. 1917. Further notes on Pseudemys at Plymouth, Massachusetts. 44: 52

Ernst, C.H., and J.E. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States, Second Edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. 827 pp

Graham, T.E. 1969. Pursuit of the Plymouth Turtle. International Turtle and Tortoise Society Journal 3(1): 10–13.

Graham, T.E. 1971. Growth rate of the red-bellied turtle, Chrysemys rubriventris, at Plymouth, Massachusetts. Copeia 1971: 353–356.

Graham, T.E. 1982. Second find of Pseudemys rubriventris at Ipswich, Massachusetts, and refutation of the Naushon Island record. Herpetological Review 12: 82–83.

Graham, T.E. 1984a. Pseudemys rubriventris (red-bellied turtle). Food. Herpetological Review 15: 50–51.

Graham, T.E. 1984b. Pseudemys rubriventris (red-bellied turtle). Predation. Herpetological Review 15: 19–20.

Gualco, N.A. 2016. Pseudemys rubriventris in Massachusetts: a spatiotemporal study of habitat use & population dynamics. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Antioch University New England.

Haskell, N.A. 1993. Genetic variation, population dynamics, and conservation strategies for the federally endangered redbelly turtle (Pseudemys rubriventris) in Massachusetts. MS thesis, Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, University of Massachusetts; Amherst. 99 pp.

Haskell, A., T.E. Graham, C.R. Griffin, and J.B. Hestbeck. 1996. Size related survival of headstarted Redbelly Turtles (Pseudemys rubriventris) in Massachusetts. Journal of Herpetology 30: 524–527.

LeConte, J.1830. Descriptions of the species of North American tortoises. Ann. Lyceum Natur. Hist. New York 3:91–131

Lucas, F.A. 1916. Occurrence of Pseudemys at Plymouth, Mass. Copeia 38: 98–100.

Regosin, J.V., M.T. Jones, L.L. Willey, N. Gualco, H.P. Roberts, and P.R. Sievert. 2017. Status of the Northern red-bellied cooter in Massachusetts. Final Report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 106 pp.

Rhodin, A.G., and T. Largy. 1984. Prehistoric occurrence of the Red-belly Turtle (Pseudemys rubriventris) at Concord, Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Herpetological Review 15: 107.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2021. Species Status Assessment Report for the Massachusetts Population of the Northern red-bellied cooter (Pseudemys rubriventris), Version 1.0. November 2021. Hadley, MA. 109 pp.

van Dijk, P.P. 2013. Pseudemys rubriventris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T18460A8299690.

Waters, J.H. 1962. Former distribution of the red-bellied turtle in the Northeast. Copeia 1962: 649.

Contact

| Date published: | March 10, 2025 |

|---|