- Scientific name: Dichanthelium scabriusculum (Elliott) Gould & C.A. Clark

- Synonym: D. aculeatum (Hitchc. & Chase) LeBlond, D. cryptanthum (Ashe) LeBlond, D. recognitum (Fernald) LeBlond

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

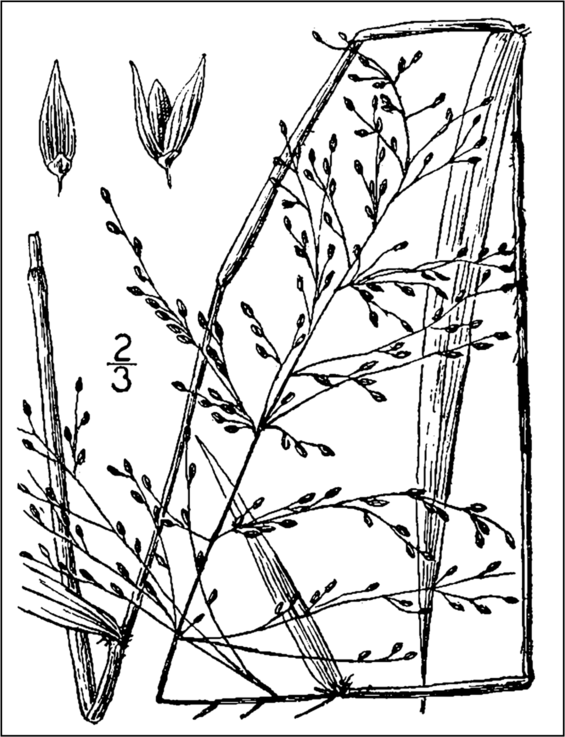

Rough Rosette-grass has open panicles, spikelets that are glabrous or sparsely pubescent, and membranous ligules.

Rough rosette-grass (Dichanthelium scabriusculum), as previously described, has been discovered to be a complex of four species of rosette-grass: prickly witchgrass (D. aculeatum), hidden-flowered witchgrass (D. cryptanthum), novel witchgrass (D. recognitum), and rough rosette-grass (D. scabriusculum [more narrowly described]). All four are similar tall (70–150 cm; 28–59 in) perennial species in the grass family (Poaceae), growing in large clumps which become increasingly branched and bushy through the summer and early fall. Like other rosette-grasses, this complex of species has open, branched inflorescences, and each spikelet contains only a single floret (a small individual flower). In this group of rosette-grasses, the inflorescences range 10-21 cm (4-8 in) tall. In late summer and early fall, rough rosette-grass produces additional panicles that are partly included in the leaf sheaths (the lower part of the leaf surrounding the stem). The leaf sheaths are hairy, and the leaf blades are 7-12 mm (0.25-0.5 in) wide and 12-25 cm (4.75-10 in) long, and taper to an involute tip.

The species in the rough rosette-grass complex look generally similar to several other rosette-grasses. In particular, deer-tongue grass (Dichanthelium clandestinum) is very common and easily mistaken for species in this complex. Deertongue grass has wider leaf blades (15-30 mm; 0.6-1.2 in) that are flat to the tip.

To positively identify species in the rough rosette-grass complex and other species of Dichanthelium, a current technical manual must be used as there have been several taxonomic changes within the genus. There are three such manuals either currently published or expected soon: Weakley et al., 2022, Naczi et al., and Haines; the last two are expected updates to northeast and New England botanical manuals, respectively and have not yet been published.

Life cycle and behavior

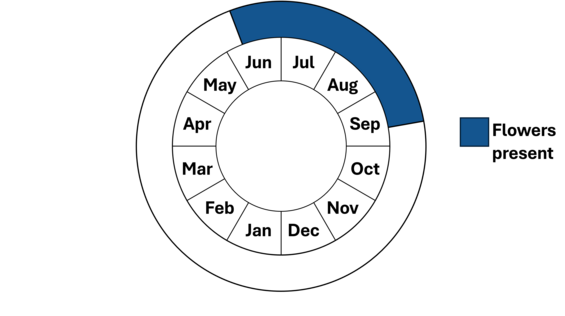

Species in the rough rosette-grass complex are rhizomatous perennial herbs that are wind-pollinated. They produce terminal panicles in the spring (vernal phase) and lateral ones in the fall (autumnal phase) branching from the mid or upper nodes. Most keys rely on the spring phase florets for identification, as the size of the florets and their parts are slightly different. The autumnal phase florets are often hidden within the leaf sheaths. Vernal phase florets are present late June or July through late summer, depending on the species.

Research into the pollination of rosette-grasses has shown that this genus relies heavily on self-pollination through cleistogamous flowers (ones that do not open). A study of the related species D. clandestinum demonstrated that the cleistogamous flowers produce ten times more seed than the open flowers fertilized by wind pollination (chasmogamous). However, the seeds produced through wind cross-pollination had greater dormancy (Bell and Quinn 1985).

There is no known seed distribution mechanism in the rough rosette-grass complex. It is assumed that gravity plays an important role with seedlings growing near parent plants.

Population status

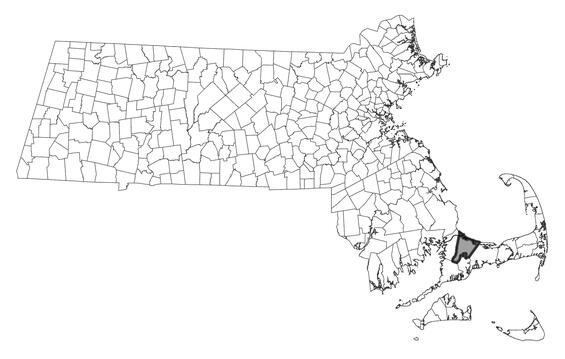

Rough rosette-grass is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as Threatened. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale, and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. Only two populations have been found in Massachusetts; one from Barnstable County has been observed within the past 25 years, while the one in Hampden County is historical. A specimen collected from the Barnstable County population has been annotated to D. aculeatum, one of the species within this complex.

Distribution and abundance

Species in the rough rosette-grass complex occur along the east coast from Vermont to Florida, west to Texas. In New England, it is known from Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont, and is considered Endangered in Connecticut and Rhode Island. No species from this complex are known in either New Hampshire or Maine.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Weakley et al. (2020) describes the habitat as “Moist, low, open or shaded woodlands, often along streams or ditches.” Magee (2014) describes the habitat as “Roadsides, waste places, river and pond margins, old fields, and open woodlands in moist or dry soil.” In Massachusetts, species from the rough rosette-grass complex have been found along a power line rights-of-way and a swale. In southern states, they are usually found in standing water, unlike the plants in Massachusetts, which may occur in seasonally wet sandy soils that dry completely later in the season.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The species in the rough rosette-grass complex are threatened by lack of correct identification as they are similar in appearance to the common deertongue grass. They are also threatened by changes in management regime where it occurs in anthropogenic habitats, including herbicide use along powerlines or roadways. Any alteration of hydrology could threaten this complex of species, as could succession.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

More surveys, including de novo surveys, are needed for this species complex. It is thought that there likely are additional populations that have not been observed in the state. It is likely that it will be found in the eastern portion of the state, and not within the calcium-rich, higher pH soils of the Berkshires. Surveys should be done during the vernal phase of flowering.

Management needs

The exact ecological needs of these species are not known as they are rare throughout their ranges. Careful management is needed to maintain open habitats for species within the rough rosette-grass complex without damaging existing populations. Sites that support rough rosette-grass should be protected from dramatic changes in hydrologic conditions. All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

Research needs

The Dichanthelium scabriusculum complex has recently been split into 4 species (LeBlonde, 2019). This group is now considered a complex of species. As Massachusetts only has had 2 populations identified as D. scabriusculum, it is unlikely that more than 2 of these have occurred in the state. At least 2 species within the complex could have been observed in Massachusetts as the habitats for the populations were very different. When plants from this complex are observed, it is important to determine which species within the complex has been observed. Flora of the Southeastern United States provides keys and description to all 4 species in the complex and is updated regularly.

As this complex of species are under-surveyed, more standard information is needed including a determination of which species has been observed and lists of associated species, comments on habitat quality and threats, and assessments of soil conditions and phenology. Research is also needed to determine whether species in this complex can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, this strategy could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Bell, Timothy J. and James A. Quinn. 1985. Relative importance of chasmogamously and cleistogamously derived seeds of Dichanthelium clandestinum (L.) Gould. Botanical Gazette 146(2): 252–258.

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany, Eighth (Centennial) Edition—Illustrated. American Book Company, New York.

Gleason, H.A., and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, 2nd edition. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

LeBlond, R.J. 2019. Three species in the D. scabriusculum complex are given names in Dichanthelium. In Weakley, A.S., R.K.S. McClelland, R.J. LeBlond, K.A. Bradley, J.F. Matthews, C. Anderson, A.R. Franck, and J. Lange. 2019. Studies in the vascular flora of the southeastern United States. J. Res. Inst. Texas 13: 107- 129

Magee, Dennis W. Grasses of the Northeast. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, Massachusetts. 2014.

USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 1: 160.

Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the southeastern United States. University of North Carolina Herbarium, North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill, NC.

Contact

| Date published: | April 14, 2025 |

|---|