- Scientific name: Sporobolus cynosuroides (L.) P.M. Peterson & Saarela

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Salt Reedgrass is a robust member of the grass family (Poaceae), growing 1-3 m (3-10 ft) tall. It is found in brackish marshes and the upper margins of salt marshes. The hard, coarse stems arise from stout underground rhizomes. Leaves from the lower stem are 8-20 mm (0.3-0.8 in) wide, with rough, sharp margins. The large, dense inflorescence has numerous straight, ascending branches attached to the central stem, or rachis, each densely set with spikelets of tiny flowers arranged on one side of the branch. The spikelets overlap each other giving a shingle-like appearance. Each spikelet has one flower with a 10-15 mm (0.4-0.6 in) second glume that extends beyond the lemma and is sharply acuminate, awnless or short-awned, and has a scabrous keel. Salt Reedgrass often occurs in almost pure stands that take on a distinctive golden hue in late autumn.

Other members of the genus Sporobolus are generally shorter than salt reedgrass, although saltmarsh cordgrass (S. alterniflorus) can reach 2 m (6.6 ft). Saltmarsh cordgrass has smooth or only slight scabrous leaf margins, whereas salt reedgrass has very rough leaf margins. Prairie cordgrass (S. pectinatus) has upper glumes with long awns (3-8 mm; 0.1-0.3 in), and lower glumes that are three-quarters or more the length of the adjacent lemma. In contrast, the upper glumes of salt reedgrass are awnless or short-awned, and the lower glumes are one-half to two-thirds the length of the adjacent lemma. Common reed or Phragmites (Phragmites australis) is another tall grass that grows in brackish marshes and is often found near salt reedgrass. The feathery inflorescence of Phragmites is denser than that of salt reedgrass, and the leaves are shorter and broader.

Technical manuals should be consulted to confirm the identification of all grass species. Characters that help to identify salt reedgrass specifically:

- Dense spikelets on one side of the branch

- Wide lower leaves with very rough margins

- Upper glume is awnless or short-awned

- Lower glume is 1/2 to 2/3 the length of the adjacent lemma

Life cycle and behavior

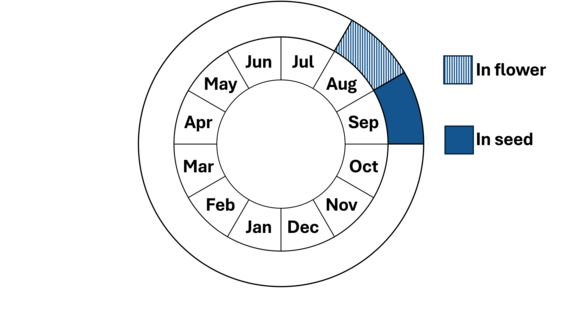

Salt reedgrass is a perennial, rhizomatous grass that is wind-pollinated. It produces flowers in August and will have mature spikelets into September. It can spread both by seed and by rhizomes.

Population status

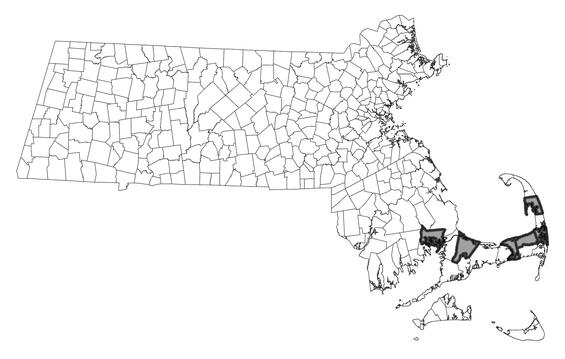

Salt reedgrass is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as threatened. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale, and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. There are currently 5 populations verified since 1999. All current records of this species in Massachusetts are from Plymouth and Barnstable Counties. Three of these populations have been ranked as doing well, one has only a few stems present and there was insufficient information to rank the fifth population. An additional 5 populations have not been observed recently, including one in Bristol County, the others occurred in Plymouth and Barnstable Counties.

Distribution and abundance

Salt reedgrass is found in brackish marshes from Massachusetts south along the coast to Florida and west to Texas. Massachusetts represents the species northern extent. In New England, salt reedgrass is critically imperiled in Rhode Island, not ranked in Connecticut, and does not occur in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Photo credit: Bruce Sorrie

Salt reedgrass colonies occur within upper (landward) portions of salt marshes, and brackish marshes along tidal rivers and estuaries, usually above the level of mean high tide. Associated species include hightide-bush (Iva frutescens), common reed (Phragmites australis), and seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Salt reedgrass grows at the upper portion of salt marshes and brackish marshes along tidal rivers. As sea levels are predicted to rise (Staudinger et al. 2024), existing habitat for this species is likely to be flooded. Non-native common reed also poses a serious threat to salt reedgrass as it is found in a wide range of wetland settings, including the brackish marshes that provide habitat for salt reedgrass. Common reed is often controlled with herbicides that can also kill salt reedgrass if misapplied. Sites supporting salt reedgrass should be monitored for invasions of common reed and other exotic species, as well as competition from native plants. Salt reedgrass is also potentially threatened by development that leads to increased runoff or siltation of wetlands, and by disruption of natural tidal flow. Sites supporting salt reedgrass should be protected from changes in light, moisture conditions, and natural tidal flow. Occasionally salt reedgrass grows near recreational trails, which can damage plants and cause soil disturbance.

Conservation

Salt reedgrass is a distinctive species that can be observed at any time of the year but is best surveyed in July or August when in flower or mature seed to rule out similar-looking species. With the predicted changes in sea levels, this species should be monitored for reduction in the current populations. If possible, monitoring should occur at least every 5 years. As with any rare species, when monitoring please note if there are threats to the populations including invasive species, shading, trampling, etc.

Sites supporting salt reedgrass should be monitored for invasions of common reed and other exotic species, as well as competition from native plants. Rare plant locations that receive heavy recreational use should be carefully monitored for damage or soil disturbance, and where necessary, trails should be re-routed to protect rare species. All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroduction. Questions about seed germination and seed storage over winter will need to be answered. As sea-level rise may create new habitat while at the same time isolating current populations, this strategy for reintroductions could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Gleason, H.A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, 2nd edition. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 3/19/2025.

POWO (2025). "Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 3/19/2025.."

Silberhorn, G. 1992. Big Cordgrass, Giant Cordgrass, Spartina cynosuroides (L.) Roth. Virginia Institute of Marine Science Technical Report No. 92-9. http://ccrm.vims.edu/publications/wetlands_technical_reports/92-9-big-cordgrass.pdf

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Contact

| Date published: | May 8, 2025 |

|---|