- Scientific name: Diplachne fascicularis (Lam.) P.Beauv.

- Synonyms: Diplachne maritima E.P.Bicknell, Leptochloa fusca (L.) Kunth ssp. fascicularis (Lam) N. Snow, Diplachne fusca ssp. fascicularis (Lam.) P.M.Peterson & N.Snow

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Note the spreading nature of this plant

Saltpond grass (Diplachne fascicularis) is a low-growing (10-50 cm; 4-20 in), spreading to weakly erect grass (family Poaceae) of coastal salt ponds. It is characterized by dense branching from the base and very narrow leaves. The leaf blades are rough to the touch on the edges, while the portion of each leaf that clasps the stem is smooth. The open, unorganized inflorescence gives this plant its other common name, salty sprangletop.

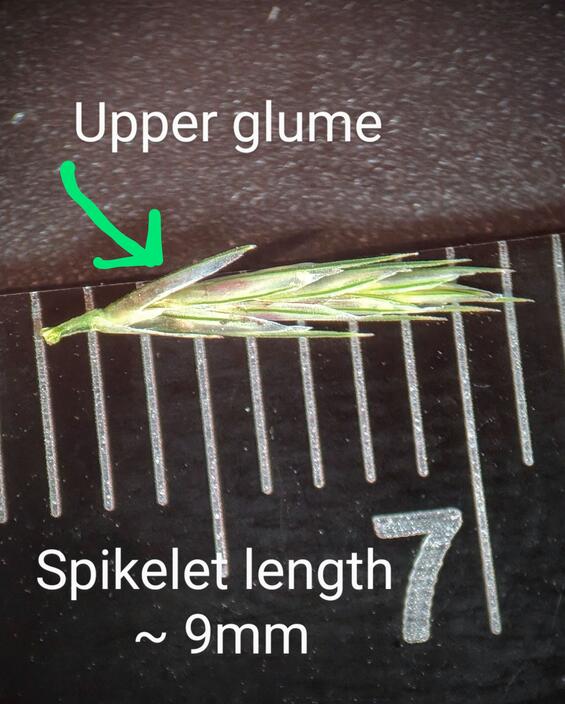

Positive identification of grasses often requires the use of specialized keys and comparison of fine details of flowering parts under magnification. The reproductive structures of grasses comprise flowers (florets) arranged in a spikelet, either singly or in clusters. Each floret is cupped by two small leaf-like bracts called the lemma and the palea, and the entire spikelet is subtended by two similar structures called glumes. Each of these structures can be modified or missing in various grass species. In saltpond grass, the spikelets, which are 5-12 mm (0.2-0.5 in) in length, bear six to twelve florets, each subtended by a lemma with a needle-like awn (2.5-5 mm; 0.01-0.02 in) emerging between two-minute teeth. Each lemma is grayish to white, and hairy with a dark spot at the base and is 4- 8 mm (0.02-0.03 in) in length. The second or upper glumes are 4-7 mm (0.02-0.03 in) long. The inflorescence, a panicle, is partially enveloped by the leaf sheath. Leaf blades are 2-7 mm (< 0.25 in) wide, and the upper ones extend beyond the inflorescence. The ligule is 2-5 mm (0.02 in), membranous, with an irregular margin.

A related upright species/subspecies that has found along highways in areas with high road salt may key to saltpond grass; it is unlike the rare species that has a low-growing, sprawling habit. Two similar exotic species have been observed in Massachusetts that are closely related to saltpond grass; these are Mexican sprangletop (Diplachne fusca ssp. uninervia) and needle sprangletop (Leptochloa mucronata). Unlike the rare subspecies, Mexican sprangletop has a panicle that protrudes from the leaf sheath, lemmas that lack a dark spot, and leaf blades that are shorter than the panicle. Needle sprangletop has a shorter ligule (0.6–1 mm; 0.02-0.04 in) than saltpond grass, and distinctive leaf sheath pubescence in which the hairs arise from pustules.

Life cycle and behavior

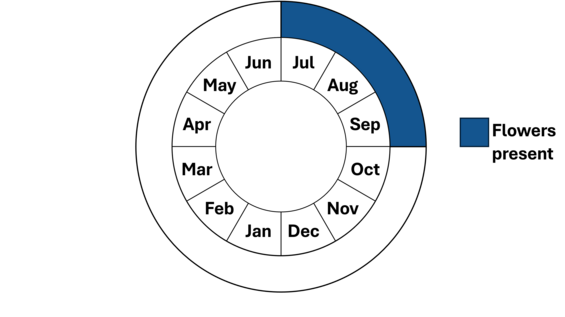

This species is an annual which sprouts when the salt pond shore is exposed. It usually produces flowers and seed sometime between July and the end of September when appropriate growing conditions occur.

Population status

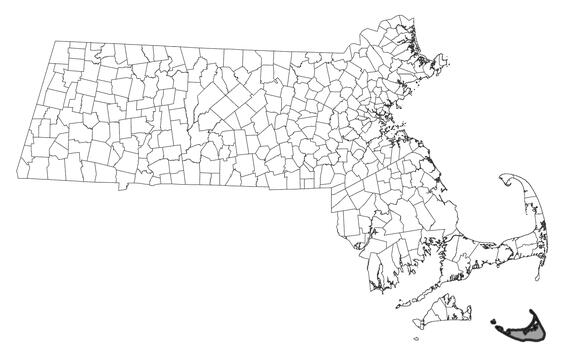

Saltpond grass is listed under Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as Threatened. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. It is currently known from only 3 populations, observed since 1999, all in Nantucket County. An additional 4 which have not been observed since 1990 in Barnstable and Dukes Counties. Two additional populations were last observed around 1900 in Nantucket County and have not been observed since. Upright plants with similar characteristics (described above) are not representative of the rare species known for its a low-growing, sprawling habit. These have been observed in at least two locations along MA highways.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Distribution and abundance

The rare saltpond grass is known along the U.S. coast from southern New Hampshire to Florida. It is thought to be possibly extirpated from New Hampshire and Rhode Island, and is considered critically imperiled in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and South Carolina, imperiled in New Jersey, and vulnerable in Delaware and North Carolina. Massachusetts represents its current northern extent. NatureServe has evaluated it as Vulnerable on a global scale (G3).

Habitat

In Massachusetts, saltpond grass is native to sandy or muddy (organic muck) shores of brackish coastal ponds, often near where freshwater enters the pond at a seep or small stream. Brackish ponds are made saline by seawater input either by high tides or stormwater over-washing a barrier beach. The water levels can be influenced by tides as well as wider groundwater conditions, and the lens-shaped profile of these ponds can lead to wide areas of emergent sandy soils with small changes in water level. As a result, saltpond grass can be found in standing water as well as on exposed sandy or muddy substrates. Associated species include saltpond flatsedge (Cyperus filicinus), sea-beach knotweed (Polygonumglaucum; Special Concern), fall panic-grass (Panicum dichotomiflorum), saltmarsh fleabane (Pluchea odorata), saltpond spike-sedge (Eleocharisparvula), and crabgrass (Digitaria spp.).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Saltpond grass grows so close to the ocean, often only a couple feet above sea level, it is particularly vulnerable to sea level rise. Although the species prefers brackish water, it does not grow on ocean beaches with regular, direct exposure to higher levels of salt water, but in brackish ponds near the ocean which usually have freshwater input. These ponds are threatened by rising sea levels (Staudinger et al. 2024).

Saltpond grass is threatened by lasting changes in water levels or chemistry (e.g., eutrophication and reduced or increased salinity), which could favor colonization by exotic invasive and aggressive native species. Browsing by Canada geese also threatens saltpond grass. Inputs of nutrients from goose waste and the surrounding landscape could induce eutrophication, especially in ponds that are cut off from tidal flow by a barrier beach. Trampling from recreational activities also could be a threat depending on the setting; locations that receive heavy recreational use should be carefully monitored for plant damage or soil disturbance.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

As an annual species, the population of this plant may vary widely from year to year depending on conditions. If possible, surveys should be conducted for three to five years in a row to capture the population at different water levels and shore exposures.

Management

In the absence of natural breaching of a barrier beach, mechanical breaching may be considered.

Sites should be monitored for colonization of aggressive competitor species; if competition by an aggressive invasive plant species threatens a saltpond grass population, a plan to control the competitors may be warranted. It might be necessary to disrupt Canadian geese feeding on this and other shoreline plants. All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

Research needs

Currently the suggested scientific name of the spreading form of the species, Diplachne maritima, is not accepted. Additional genetic studies are needed to confirm separation of upright plants found along highways and the low-growing, sprawling plants found on salt pond shores.

Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. Questions about seed germination and seed storage over winter will need to be answered. As sea-level rise may create new habitat while at the same time isolating or inundating current populations, this strategy for reintroductions could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Barkworth, M.E. et. al. (ed). Flora of North America. Volume 25. Oxford University Press. 2003.

Gleason, Henry A. and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, New York. The New York Botanical Garden. 1991.

Haines, Arthur. “Addenda to Flora Novae Angliae.” November 22, 2022, Go Botany. https://newfs.s3.amazonaws.com/docs/Flora_Novae_Angliae_Addenda_22Nov22.pdf

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 3/14/2025.

POWO (2023). "Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/results?q=Diplachne%20maritima, retrieved December 13, 2024

Sorrie, B.A. 1987. Notes on the rare flora of Massachusetts. Rhodora 89:113-196

Weakley, A. S., R. J. LeBlond, B. A. Sorrie, C. T. Witsell, L. D. Estes, K. Gandhi, K. G. Mathews, and A. Ebihara. 2011. New Combinations, Rank Changes, and Nomenclatural and Taxonomic Comments in the Vascular Flora of the Southeastern United States. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 5: 437–455

Contact

| Date published: | April 14, 2025 |

|---|