- Scientific name: Aristida tuberculosa Nutt.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Seabeach needlegrass (Aristida tuberculosa). Photo credit: Grace Glynn

Seabeach needlegrass (Aristida tuberculosa) is an annual grass of medium height (30-60 cm [10-25 in]) with a small fibrous root system. It grows in patches, which from a distance have a coppery hue. Plants produce one to several shoots from a central point at ground level. These shoots have few leaves (1-3 mm [0.04-0.12] wide) but support several flowering spikes tipped by long awns. The lower leaf sheaths are villous (finely pubescent) while the upper sheaths are essentially hairless. In immature flowering plants, the awns stick straight up. When seeds mature in late summer or early fall, the awns turn a pale straw color, coil tightly around the basal portion, and project perpendicularly to the stem. These twisted awns aid in the implantation of the seed, which will not germinate unless buried. The dried leaf margins become involute (roll inward) at the end of the season.

The perennial purple needlegrass (Aristida purpurascens, Threatened) is similar in appearance but is darker, having a more purple-brown hue. Its inflorescence has a narrower appearance due, in part, to the shorter awns (1.5-2.5 cm [0.6-1 in] versus 2.5-5 cm [1-2 in] in A. tuberculosa), which are not coiled at the base. Purple needlegrass is a rare plant of dry grasslands and is not found in the dunes where seabeach needlegrass grows.

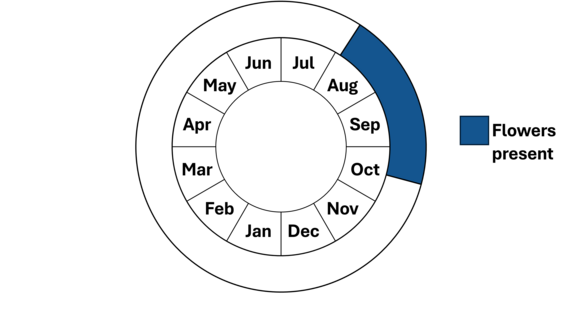

Life cycle and behavior

Both species of rare needlegrass grow and produce leaves much earlier in the season than they can be confidentially identified. Identifiable seed is present August through October. The mature florets with dry awns are needed to identify this grass to species. Like most grasses, it is wind pollinated. In dry conditions, the awns spread wider and may be more easily pulled off into the fur of passing animals. Once the seeds fall off a passing animal or the parent plant, the awns are thought to work to push the seeds into the soil with alternating damper and drier weather cycles.

Population status

Photo credit: Robert Wernerehl

Seabeach needlegrass is listed as Threatened in Massachusetts. It ranges from New Hampshire west to Minnesota and south to Mississippi and Florida. It is also considered rare in most states where it occurs, including Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina and Virginia. It has not been assessed in 5 states where it occurs. In New England, it is not known from Maine, Rhode Island or Vermont.

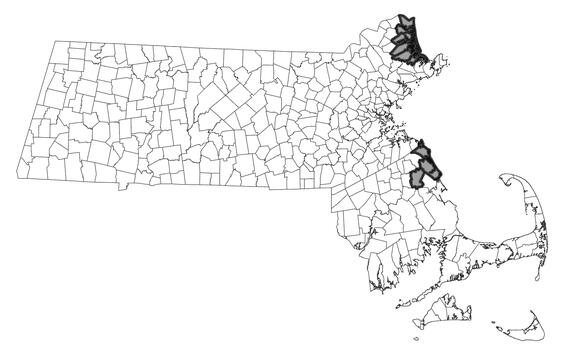

Distribution and abundance

In Massachusetts, seabeach needlegrass has been observed in 13 locations. Of those, only 7 populations have been observed in the last 25 years in Essex, Suffolk and Plymouth counties. Previously there was a population observed in Middlesex County as well. Despite the low numbers of total populations, 3 or almost half, are doing well with large healthy populations. For unknown reasons, this species has never been found on the extensive dune systems of Cape Cod and the Islands.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Photo credit: Robert Wernerehl

Seabeach needlegrass is found on stable dunes mostly in sandy, sparsely vegetated conditions. It is often found growing near or in association with beach heather (Hudsonia tomentosa), coastal jointed knotweed (Polygonum articulatum), seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), beach pinweed (Lechea maritima), Greene’s rush (Juncus greenei), sea-beach sedge (Carex silicea), and poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Occasionally it is also found in gravel pits or on sandy roadsides, since this species is somewhat adventive and can colonize disturbed sites.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The primary threat to this species is beach erosion. This can result from many causes, including heavy recreational use of the dunes especially by off road vehicles (ORVs) which may result in destabilization and loss of habitat. Further habitat loss occurs with the succession of the habitat from its early open stage to shrub and pine thickets. This species does not tolerate the invasion of its habitat by the exotic beach rose (Rosa rugosa) or other shrubs. Populations of this species are threatened by sea level rise and more severe storms impacting and eroding the dune areas where it grows. Such storms are a predicted result of climate change (Staudinger et al. 2024). Some populations have experienced substantial browse by rabbits. An additional threat is “beach nourishment” with sand, which would cover the habitat with sand. Finally, in one large population, trail creation through the population resulted in plants being trampled.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

The best time to survey this population is when it has mature seed, from August into October. It is a beautiful, distinctive grass so it is rewarding to survey and find. Because the awns contract and extend depending on the humidity, it is easiest to survey on a clear, dry sunny day. Many of the smaller older populations had not been surveyed for several years and seem to have now disappeared. When surveying, it is important to note whether other vegetation is starting to crowd out this species, whether there is erosion occurring or if there are other threats to the population. This is an annual species, and the population numbers are expected to vary each year, sometimes widely. It is very helpful to have more frequent surveys to understand the real extent of the population.

Management

The populations need open areas with a low level of disturbance to keep them open. Exotic species, including Rosa rugosa, may shade this plant and prevent it from growing. Any plan to do management within populations of rare species needs to be discussed with MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage Endangered Species Program (NHESP), and a permit may be needed to ensure the population is not damaged.

Research needs

The exact ecological needs of this species are not known. For example, why has this species never been found on Cape Cod or the Islands, and could it grow there if an appropriate site were located? Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. Questions about seed germination and seed storage over winter will need to be answered. As sea-level rise may create new habitat while at the same time isolating current populations, could populations be transplanted to these new areas? This strategy for reintroductions could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species. In addition, greenhouse studies have indicated that the awns on the seeds will complete self-burial with changes in humidity. It is not known whether this will occur as successfully in a natural setting.

References

Collins, Beverly S. and Gary R. Wein. 1987. “Mass Allocation and self-burial of Aristida tuberculosa florets” Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 124(4), 1987, pp. 306-311.

Haines, Arthur. Flora Novae Angliae. New England Wild Flower Society, Yale University Press, 2011.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 1/2/2025.

POWO (2025). "Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Retrieved 06 January 2025."

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D’Amato. A Regional Synthesis of Climate Data to Inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86 2024

Contact

| Date published: | March 25, 2025 |

|---|