- Scientific name: Isotria medeoloides (Pursh) Raf.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Threatened (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Plant in flower. Photo credit: Karro Frost

Small whorled pogonia (Isotria medeoloides) is a perennial herbaceous species in the orchid family (Orchidaceae). Its thick fleshy stem grows up to 25 cm (10 in) tall when flowering and up to 35 cm (14 in) when fruiting. The stem ends in a whorl usually 5 pale-green elliptic leaves that are 2.5-9 cm (1 to 3.5 in) in length. One or two lime-green flowers (about 2 cm [0.75 in] long) grow from the center of the whorl on short stalks. The flowers are composed of three petals, the lowest of the three having a greenish lip at its tip. Surrounding the petals are three separate, narrow, pale green sepals (outer floral leaves) which grow between 1.25-2 cm (0.5-0.75 in) long. Fruiting capsules are erect; the fruit stalk length is approximately equal to or slightly shorter than that of the capsule (1-1.5 cm [0.4-0.6 in] long).

Large whorled pogonia (Isotria verticillata) (on the plant watch list) is similar to small whorled pogonia but can be distinguished from the latter during the growing season by the shape of the sepals. Sepals of large whorled pogonia are over 3.75 cm (1.5 in) long, purplish, and wide-spreading. The sepals of small whorled pogonia are much shorter (approximately 2 cm [0.8 in]), greenish, and are situated more closely to one another. The stem of large whorled pogonia is often tinged with purple, while small whorled pogonia never has a purplish color to its stem. Large whorled pogonia forms colonies and small whorled pogonia grows as individual plants, often widely separated from each other. Finally, the peduncle (stem for the flower and capsule) is 2-5.5 cm (0.75-2 in) long, much longer than the peduncle on small whorled pogonia. Another species, cucumber root (Medeola virginiana), a plant of the Lily family, is also similar in appearance to the small whorled pogonia as it also has 5 whorled leaves at the top of a stem. However, cucumber root stems are wiry and often covered by a white fuzzy material.

Life cycle and behavior

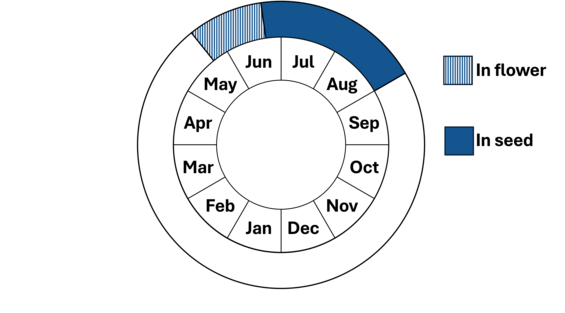

Small whorled pogonia can remain dormant for up to ten years, making its reproductive history difficult to study and its age difficult to determine. Growth is initiated in early to mid-May and flowering by the end of May. The flowers last for 7 to 10 days. This species mostly self-pollinates. The leaves turn yellow and die in September and seeds are expelled from their capsules after October 15 by wind. Like many orchids, small whorled pogonia depends on mycorrhizae fungi to help its seeds sprout and grow. It remains underground for many years before emerging as a young plant and may only produce leaves for the first few years that it grows above ground before it starts to flower. The mycorrhizae supporting this plant feed mostly on decaying wood on the forest floor, so one may find plants growing in a ring around dying or dead standing trees.

Population status

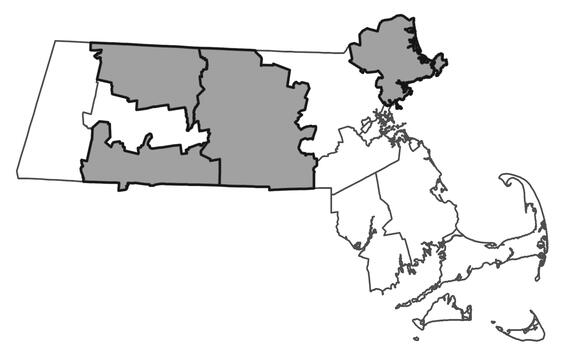

Small whorled pogonia is listed as Threatened by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service and as Endangered by MassWildlife. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. There are currently 9 occurrences in the state verified since 1999 found 4 counties: Essex, Franklin, Hampden, and Worcester. Two additional populations have not been observed within the past 25 years. A third population is only known from an herbarium sheet with no locational data.

The lack of suitable habitat is the most significant factor contributing to small whorled pogonia’s rarity. Specifically, habitat destruction and alteration combined with vandalism and illegal plant collection threaten Isotria medeoloides. As this species is so rare, it is sought after by collectors who have illegally uprooted and destroyed individual plants for specimen collections. Small whorled pogonia cannot be successfully transplanted, so any plants that are uprooted are lost forever.

This orchid requires very specific habitat to succeed and will not occur in other areas. Although the plant is found along vernal streams and in thick, highly acidic organic duff, the surrounding land is equally important to the success of this orchid. This species relies on water moving from upslope regions down to its populations. When these vital buffer zones are altered, water movement is disrupted and the microclimate of the area often changes, creating a different habitat in which Isotria medeoloides cannot grow. It is believed that it is as important to preserve these peripheral areas as it is to preserve the habitat on which the plants occur.

Distribution and abundance

Small whorled pogonia is found in Maine and Ontario in the north, west to Michigan, and south along the eastern seaboard to Georgia. It is rare throughout its range, with the largest concentrations occurring in Maine and New Hampshire. Historically small whorled pogonia had disjunct populations in Illinois, Michigan and Missouri, but all the populations in all three of those states are now considered extirpated, as are populations in Maryland. This species is one of the rarest orchid species in northeastern North America. As of 2020, there were thought to be less than 300 extant populations of Isotria medeoloides worldwide, with fewer than 3,000 individuals total. It is considered critically imperiled or imperiled in every state where it occurs. In New England, it is considered critically imperiled in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont; and imperiled in Maine and New Hampshire (NatureServe, 2025).

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Note peduncles shorter than capsule. Photo credit: Karro Frost

Historically, the habitat supporting Isotria medeoloides was not well documented. In recent years, however, this species’ habitat has been consistently reported as forested slopes composed of “very stony fine sandy loam” soil types where water movement is restricted by a fragipan. Fragipans are brittle loamy cement-like layers below the surface of the soil which are low in porosity and force the water to drain laterally instead of vertically. The soil above the fragipan is very acidic and low in nutrients. In Massachusetts, this plant is found on slightly sloping, previously logged forest land made up of acidic and granitic soils. Like other sites known to support this orchid, the Massachusetts sites are composed of seasonally moist areas above a fragipan. Light conditions are usually filtered rather than shaded or open.

A significant number of plants are associated with this type of habitat and are considered indicator species for the rare orchid when they are found together in plentiful numbers. Associated forest species include: red maple (Acer rubrum), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), red oak (Quercus rubra), white pine (Pinus strobus), beech (Fagus grandifolia), large-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata). A natural community including paper birch with dense fern undergrowth is often associated with Isotria medeoloides. Also, witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) is always abundant where Isotria medeoloides grows.

Associated herb species (when they are present) are woodland ferns such as hay-scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula), New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis), and cinnamon fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum) and interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana). Evergreen herbaceous species found are: wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), mayflower (Epigaea repens), spotted wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata), partridgeberry (Mitchella repens), and shinleaf species (Pyrola spp.). Other species of orchids which are often found with small whorled pogonia are: pink lady’s-slipper, (Cypripedium acaule), rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera pubescens), and coralroot species (Corallorhiza maculata and C. odontorhiza).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Due to the rarity of this species, not all the threats may be known. It is thought that the primary threat to this species throughout its range is habitat destruction for residential or commercial development. Even if development does not directly impact populations, it helps to concentrate deer populations, and the risk of deer browse on small whorled pogonia will increase. Logging is another potential threat. However, a total lack of disturbance in its habitat may lead to excessive shading that will eliminate this species from a site. Although this is a forest growing species, if the forest canopy becomes too dense, the population of small whorled pogonia will decline, and may rebound only when there is wind throw or cutting to open the canopy. Recently it has been found that the primary mycorrhizae supporting small whorled pogonia is one associated with beech (Fagus grandifolia). Impacts to beech such as beech bark disease and beech leaf disease are likely to impact small whorled pogonia as well.

Conservation

Populations of small whorled pogonia is surveyed ever year or two in Massachusetts. If not found during one survey, it is worthwhile to survey again over the next several years as the species can remain underground for years waiting for the “right” conditions to re-emerge. The best time to survey small whorled pogonia is from late May to late August. Each plant observed in a separate genet.

As with many rare plant species, the exact management needs of small whorled pogonia are not known. Management activities needed may include selective cutting of trees within the population to allow more light to reach the forest floor and provide dead wood for the mycorrhizae fungi which support the plants. Removing invasive plants in the vicinity of the population may be important as well. If there is trail near a population, the trail may need to be rerouted.

This globally rare species has had substantial research done on it, and yet there remain the main questions of, why is this species so rare and what can we do to ensure that it remains part of the biodiversity of Massachusetts? Surveys in additional potential habitat are needed. In the past 10 years new populations were found in Essex and Franklin County, and additional de novo surveys should occur.

References

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 3/31/2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 3/31/2025.

Contact

| Date published: | April 25, 2025 |

|---|