2023 Emergency Action to narrow the recreational slot limit

Massachusetts enacted new regulations for the recreational striped bass fishery in 2023 which narrowed the recreational slot limit from 28 to <35” to 28 to <31” for the one fish that anglers are allowed to retain per day. This change was required by the interstate fishery management plan for striped bass. Specifically, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Striped Bass Management Board (Board) voted on May 2, 2023 to take emergency action to require a 31" maximum size limit for all recreational striped bass fisheries coastwide. States had until July 2, 2023 to implement this requirement. The new rules took effect in Massachusetts on May 26, 2023.

Explore more about this change and why it was adopted.

Why was an Emergency Action taken in 2023?

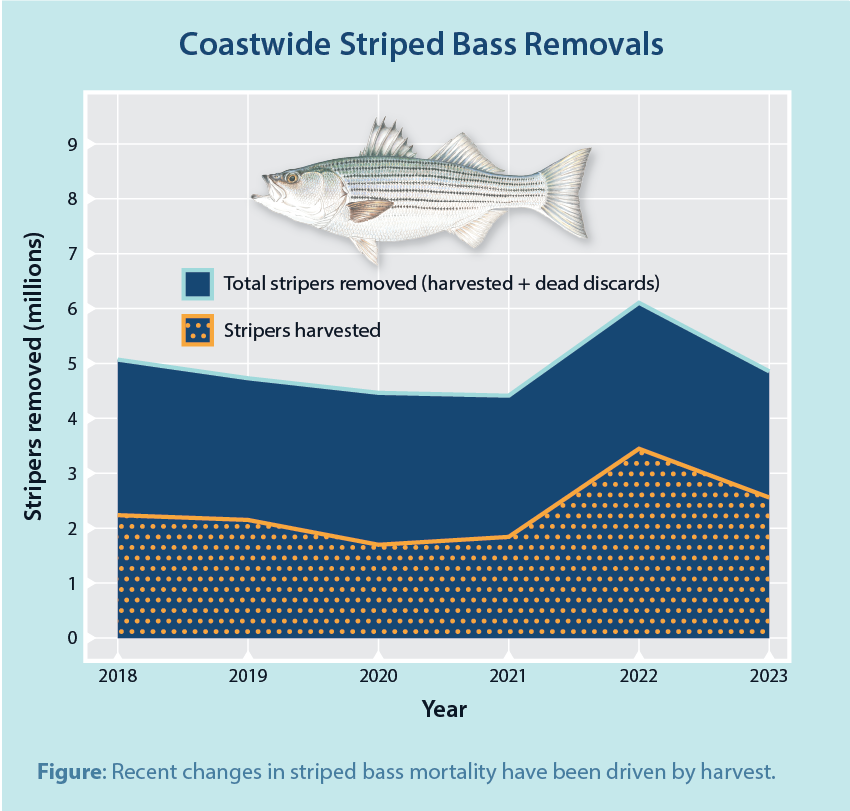

The basis for taking emergency action in 2023 was that striped bass recreational harvest coastwide nearly doubled in 2022. This unexpectedly high harvest greatly reduced the probability of rebuilding the overfished striped bass stock by 2029, which is the goal of the interstate management plan. Put another way, so many more striped bass were caught in 2022 than were expected that the existing measures to ensure striped bass remain plentiful for years to come no longer appeared effective. The main reason for the increase in harvest was that striped bass from the abundant 2015 year-class, those fish born in 2015, had begun to reach harvestable size under the 2022 slot limit (28" to <35"). Like people, fish grow at different rates and in 2023, the 2015 year-class was expected to be almost entirely recruited into this size range. This meant nearly all would be available for harvest if the slot remained 28" to <35", suggesting the potential for even greater recreational harvest in 2023 without swift action to amend the slot limit.

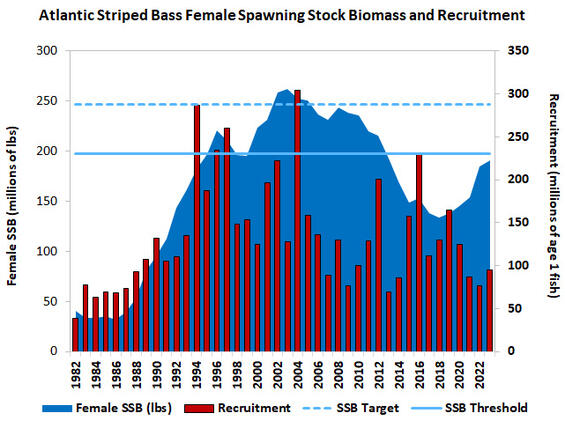

The 2015 year-class is important to the future of striped bass because it is one of the few large year-classes that has been produced in the past 20 years. Striped bass can survive more than 30 years and spawn more than 20 times, and this capability evolved in stripers (and many other fish) to compensate for years when the weather or other factors would lead to poor survival of their young. Since 2005, survival of newborn striped bass has been mostly below average, including some of the lowest recorded in recent years (see figure below). With fewer surviving striped bass born in many of the years before and after 2015, it is important for as many bass from the 2015 year-class to grow to spawning size and have as many opportunities to reproduce (and hopefully create additional strong year-classes) as possible if we hope to recover the stock and maintain a strong fishery in our coastal waters.

What was the rationale for a 31" maximum size limit?

The 2015 year-class turned 8 years old in 2023, with an average size of about 31 ½" in length. DMF age data from recreational fishery samples suggested that the new 28" to less than 31" slot along the coast would protect more than half of the 2015 year-class from recreational harvest in 2023 (compared to very little protection with the 28" to <35" slot). This level of protection will increase in future years as these striped bass continue to grow.

Figure: Comparison of the old slot (28" to <35") to the new slot (28" to <31").

The Board maintained a slot limit approach for several reasons, as opposed to transitioning to a higher minimum size (35" for example). When the Board originally went to a slot limit, the 28" minimum was maintained to make sure that shore-based anglers had opportunities to harvest striped bass, and this remains important. The application of a maximum size has had a lot of support among anglers as a way to protect the largest and most fecund female fish. Finally, beginning in 2024, the 2015 year-class would begin to shift into the greater than 34" grouping, meaning a higher minimum size alone would not be a good way to protect the 2015 year-class moving forward.

If striped bass are at risk of not rebuilding, why is the fishing so good?

Many anglers in Massachusetts enjoyed great success catching fish in the 28" to less than 35" slot in 2022, especially as compared to the first years it was in effect. This was directly tied to the highly abundant 2015 year-class, compared to the prior three years’ poor year classes. In 2022, a little more than half of the 2015 year-class had grown large enough to be harvested in the slot. DMF recreational sampling data indicate that the 2015 year-class made up 55% of harvested fish in 2022. Under the 28 to <31” slot in 2023, the 2015 year-class still contributed to superb catch and release fishing and many were still within the slot for anglers who wanted to harvest a fish.

Fishing can also be very dependent on how much and how consistently bait is in state waters. For example, the extended presence of very large and predictable schools of menhaden in Massachusetts Bay in 2022 led to great fishing, but high harvests and catches. With the coastal resurgence of menhaden, anglers in many other states enjoyed similar great fishing, contributing to the surge in coastwide recreational harvest.

Were the recreational catch estimates reliable enough to justify the Emergency Action?

Annual estimates of recreational harvest and catch of striped bass are regarded as being among the most reliable for all species because of a large sample size. For instance, Massachusetts DMF alone collects striped bass catch data from over 4,000 anglers each year. As a result, the measure of uncertainty in the estimate is the lowest of all managed species. Whereas recreational catch estimates may have precision issues when evaluated at finer levels (i.e., by state, by season, or by angler fishing mode), we have complete confidence that the large increase in coastwide annual harvest in 2022 compared to 2021 was real, and the emergency action to reduce recreational harvest was justified.

The survey methods of the national program used to estimate catch in marine recreational fisheries are constantly under review to enable continual improvement. The methods include two key components: a survey to estimate catch per trip and a survey to estimate fishing effort, which together can be used to estimate total catch. In August 2023, NOAA Fisheries, which oversees these recreational fishing surveys, announced the findings of a pilot study it conducted to evaluate potential sources of bias in the questionnaire design for the fishing effort survey. This study found switching the sequence of questions resulted in fewer reporting errors and fishing effort estimates that were generally 30 to 40 percent lower for shore and private boat modes than estimates produced from the current design. However, results varied significantly (by state and fishing mode) and because of the limited sample size, are not appropriate for management use. These results prompted NOAA Fisheries to conduct a much larger follow-up study over the course of 2024–2025, which may lead to a revised timeseries of recreational catch estimates being available in 2026. Even if we were to assume that striped bass recreational catch was overestimated by 30 to 40% over the timeseries, it would likely only change the amount of the biomass but not the overall downward trend in the population that we have seen since 2010. It would not change the fact that, using the same survey methodology, recreational harvest estimates nearly doubled from 2021 to 2022.

Why was the Emergency Action taken without formal public input?

The information regarding the large increase in 2022 harvest only became available in March of 2023. The only way for the Striped Bass Board to react quickly to decrease the harvest for 2023 was to implement an Emergency Action. All other avenues of rulemaking would have taken many more months and the opportunity to protect the 2015 year-class at its peak vulnerability would have been lost.

Prior to the May 2, 2023 meeting, the Striped Bass Board received thousands of public comments urging the Board to take swift and significant action to put the stock back on track to rebuild. Additionally, the ASMFC subsequently held four virtual public hearings on the emergency action and DMF also held a state-specific public hearing on the state’s implementation of the emergency measures. The Board also initiated an Addendum to consider management options after the Emergency Action’s expiration, ensuring a fully public process would inform measures for 2024 (see our FAQ on Addendum II for more information).

Did all the states implement the Emergency Action?

The Striped Bass Management Board allowed states up to two months to implement the 31" maximum size limit after its adoption on May 2, 2023, as the states have different processes and requirements for enacting rule changes. All Atlantic coast states implemented the Emergency Action’s 31" maximum size limit by the July 2, 2023 deadline. In Massachusetts, DMF enacted emergency recreational regulations to change the maximum length limit for keeping striped bass on May 26, 2023, similar to the timing of other New England states.

Why didn’t the Emergency Action reduce commercial quotas?

In 2022, the commercial fishery, which is managed under a hard quota, had no increase in harvest while the recreational fishery harvest almost doubled. Therefore, the 2023 Emergency Action was directed at the sector that was responsible for the great increase from 2021 to 2022. However, the Board also committed to considering changes to the commercial measures for 2024 through an Addendum to the Striped Bass Management Plan that it initiated at the same time as the Emergency Action. Addendum II, approved in January 2024, included a 7% reduction in commercial quota (see our FAQ on Addendum II for more information).

How did the Emergency Action affect the Chesapeake Bay recreational fisheries?

The 31" maximum size limit also applied to the Chesapeake Bay recreational fisheries. While the minimum recreational size in the Chesapeake Bay is smaller than the ocean fisheries— resulting in a wider slot limit—the 2015 year-class was still afforded the same protection in the Chesapeake Bay by the 31" maximum size limit. The Board’s emergency action exempted only a short, seasonal fishery for larger fish in the Chesapeake Bay in 2023 because this fishery had a minimum size limit (35") that would already protect the 2015 year-class and the timing of the fishery (May 1–15) made it irrelevant to the action taken by the Board given the July 2, 2023 implementation deadline. The Chesapeake Bay rules were further revised in 2024 under Addendum II (see our FAQ on Addendum II for more information).

Striped bass regulations in the Chesapeake Bay differ from coastal waters under a long-standing alternative management regime based on the species’ life history. The Chesapeake Bay is the main producer area of young striped bass, and those fish gradually begin to emigrate from the bay as they grow, with almost all bass becoming coastal migrants by the time they reach 34". This leads to bass larger than 28", and especially bass larger than 34", only being in the bay just before and during the spring spawning season. The remainder of the year the Chesapeake Bay is largely populated by smaller, not-yet migratory striped bass and regulations are tailored to allow anglers to pursue these fish. In 2023, the minimum recreational size limit in the Bay ranged between 18” and 20” depending on jurisdiction (Maryland, Virginia, District of Columbia, and Potomac River Fisheries Commission).

Won’t the narrower slot limit increase discard mortality?

Recreational discard mortality has exceeded recreational harvest mortality in some recent years so this is an important consideration in the species’ management. While the new 28" to less than 31" slot limit could be expected to result in more fish in the 31" to 35" size range being released, only a small portion of those fish die as a consequence of being caught and released—whereas all fish die when caught and kept. Using the accepted 9% discard mortality estimate for released striped bass, fish that would otherwise have been kept have a 91% reduction in mortality, and this reduction in harvest mortality was anticipated to offset the potential increase in discard mortality. A review of the 2023 catch data show that coastwide recreational fishery removals (harvest and dead discards combined) were about 20% lower than in 2022, in line with the Emergency Action’s objective.

Additionally, anglers can—and should—play a part in minimizing discard mortality with proper fish handling and release techniques. DMF encourages anglers to educate themselves on best handling practices to maximize survival of striped bass after the catch. DMF has also been studying the post-release mortality of striped bass to improve estimates of post-release mortality in the striped bass fishery.

How long are the Emergency Action measures effective?

ASMFC Emergency Actions are temporary and must be replaced by a formal management plan change (i.e., Amendment or Addendum), otherwise the measures revert to those previously in place upon the Emergency Action’s expiration date. When first adopted, the Emergency Action would have been in place for 180 days—through October 28, 2023. However, in August 2023, the Board extended the Emergency Action for an additional year—through October 28, 2024—unless sooner replaced by new management under Addendum II (which it had initiated in May 2023 at the same time as approving the Emergency Action). On January 24, 2024, the Board approved Addendum II to the Fishery Management Plan with an effective date of May 1, 2024. This means that the Emergency Action expired on April 30, 2024. However, Addendum II continues the 28–31” slot limit for the coastal recreational fishery (see our FAQ on the 2024 Addendum II Measures for more information.

2024 Addendum II FAQ

In 2024, Massachusetts maintained the recreational harvest allowance for 1-fish in a slot limit of 28 to <31”, reduced the commercial fishery quota by 7%, and strengthened the recreational filleting requirements. These measures were required by the interstate fishery management plan for striped bass, specifically Addendum II, which all states were required to implement by May 1, 2024.

Explore more about Addendum II.

Why was Addendum II adopted?

Addendum II was adopted to support the overfished striped bass stock’s rebuilding plan. In May of 2023, the Striped Bass Management Board received updated stock projections that indicated the rebuilding trajectory was in jeopardy without management changes. The number of striped bass caught in 2022 was much greater than expected and catch in future years was predicted to be high enough that the existing measures to ensure striped bass remain plentiful for years to come no longer appeared effective.

The Board responded in two ways: with a temporary emergency action requiring states to implement a 31” maximum size limit for recreational fisheries in 2023 (see our FAQ on the Emergency Action for more information); and with the initiation of Draft Addendum II to consider what measures—both recreational and commercial—were needed for 2024 to achieve the target fishing mortality rate. Technical analyses suggested the need for a roughly 14% reduction in overall fishery removals from 2022 removals to achieve the fishing mortality target in 2024.

As compared to the 2023 emergency action, the addendum represents the more typical management pathway which provides for multiple options to be considered and public comment to be heard and incorporated into the decision-making process. The Board approved Draft Addendum II for public comment at their October 2023 meeting. Fifteen public hearings were held coastwide (including two in Massachusetts) during the next two months. Over 2,800 comment letters plus oral testimony from nearly 700 hearing attendees were reviewed by the Board in January 2024, prior to their taking final action on management measures for 2024 under Addendum II.

How does Addendum II change the interstate management plan?

Addendum II adopted the following measures with a May 1, 2024 implementation deadline:

- For the ocean recreational fishery, a 28–31” slot limit, 1-fish bag limit, and the seasons in place in 2022;

- For the Chesapeake Bay recreational fishery, a 19–24” slot limit, 1-fish bag limit, and the seasons in place in 2022;

- Two requirements for states that authorize filleting in a recreational fishery: racks must be retained, and not more than two fillets per legal fish can be possessed;

- For the commercial fisheries, 7% reductions to the state-by-state ocean quotas and the shared Chesapeake Bay quota; and

- A mechanism allowing the Board to respond to a stock assessment with new management measures via Board action (rather than the addendum process) if the stock is not projected to rebuild by 2029 with at least a 50% probability.

Addendum II essentially continued the 2023 emergency action’s measures for the ocean recreational fishery and established new restrictions for the Chesapeake Bay recreational fishery and commercial fisheries coastwide. Prior to the emergency action, the ocean recreational fisheries were managed with a 28-35” slot limit, 1-fish bag limit, and the seasons in place in 2017—or approved alternative management programs determined to be provide equivalent conservation. The Chesapeake Bay recreational fisheries differed in having an 18” minimum size requirement (due to a long-standing management approach allowing for lower size limits in the Bay based on the size availability of fish) or conservationally equivalent measures. Addendum II re-standardized the recreational size and bag limits along the coast and in the Chesapeake Bay, and because the stock is overfished, requests for new conservation equivalency programs for non-quota managed fisheries were not allowed during the states’ implementation on Addendum II.

What measures changed in Massachusetts as a result of Addendum II?

Addendum II requires Massachusetts to:

- Maintain the recreational fishery’s one fish at 28" to less than 31" slot limit, year-round.

- Reduce the state’s commercial striped bass quota by 7%, from 735,240 pounds to 683,773 pounds, with no change to the 35" minimum size limit.

- Revise the state’s allowance for captains and crew of for-hire fishing vessels to fillet striped bass for their customers to include a requirement that the racks (i.e., carcasses) be retained and no more than two fillets per legal fish be in possession.

Only the third item above required a change to the state’s fishery management regulations. Due to the implementation deadline, DMF used its emergency rulemaking authority to revise the state’s recreational striped bass filleting rules for compliance with Addendum II and to improve their enforceability effective May 1, 2024. Such emergency regulations are then subject to a public comment period before they can be made permanent. Based on the public comment received, the final recreational filleting regulations differed in some ways from the temporary emergency measures.

Under the final rules, anglers fishing from a private vessel or shore may not fillet striped bass until ashore (unless for immediate consumption) and until all fishing has ceased and all gear is stowed. For-hire captains may fillet striped bass for their patrons during a for-hire trip provided the racks are retained until the trip has ended and the patrons have departed the vessel. No more than two fillets per fish with a minimum two square inches of skin intact may be in possession by any person until they reach their domicile.

How long will the Addendum II measures be in place?

The Addendum II measures will remain in place until revised by another addendum or amendment to the fishery management plan. Typically changes in stock condition or other management issues identified by the Striped Bass Management Board are what leads to a new management document being initiated.

In December 2024, the Striped Bass Management Board initiated Draft Addendum III to consider if additional recreational and commercial measures are needed in 2026 to support stock rebuilding. The Board was responding to the results of the 2024 Stock Assessment Update. While the assessment indicates the resource is no longer experiencing overfishing, it remains overfished and the range of short-term projections in the assessment estimate the probability of rebuilding by 2029 may be less than 50%. The Management Board is expected to consider final action on Draft Addendum III by October 2025 at the latest, such that states would have several months to implement any new measures for 2026.

2024 stock assessment and possible 2026 management changes

In December 2024, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) Striped Bass Management Board initiated Draft Addendum III to Amendment 7 to consider management actions in response to the 2024 Stock Assessment for Atlantic Striped Bass. The Addendum has the potential to change commercial and recreational fishery regulations coastwide beginning as soon as 2026.

Explore more about these possible upcoming management changes.

What is the latest stock status of striped bass?

The ASMFC’s 2024 Striped Bass Stock Assessment found that the coastwide striped bass population was not experiencing overfishing but remained overfished as of 2023 (the last year of data in the assessment). Whether the stock is experiencing overfishing is based on the magnitude of fishery removals (expressed as an annual fishing mortality rate, “F”), while whether the stock is overfished is based on the biomass of reproductively mature females in the population (or spawning stock biomass, “SSB”).

In 2018, SSB hit a point that was below the threshold level, triggering a plan to rebuild SSB to the target level by 2029. SSB has been increasing since then to be just 3% below the threshold level at which it will no longer be considered overfished (and 23% below the target level at which it will be considered rebuilt).

Fishing mortality in 2023 was between the target and threshold levels, having decreased significantly from 2022 when it jumped up above the threshold level. This overfishing in 2022 was caused by the above average 2015 year-class entering the (then) 28-35" coastal recreational slot limit, leading to an unexpected near doubling of recreational harvest. The assessment confirmed that the Emergency Action to narrow the slot limit to 28-31” in 2023 was needed and successfully returned F to below the threshold level and near the target level. (See our previously published FAQ on the Emergency Action for more information.)

Striped bass stock assessments also provide annual estimates of age-1 recruitment (how many fish survive the first year of life, an indication of year-class strength) and abundance (the total number of fish of all ages in the population). These trends are also worthy of review. Regarding recruitment, six of the last seven year-classes estimated in the assessment were below average; only the 2018 year-class has been above average since the strong year-class produced in 2015. Because of this recent string of mostly poor recruitment, the estimates of total abundance show an overall declining trend since 2016. This differs from the trend in SSB, which has recently increased as the 2015 and 2018 year-classes reached maturity. Because striped bass begin reaching maturity at age 4 but are not all mature until age 9, SSB will likely continue to increase for several more years while overall abundance will likely continue to decline unless recruitment improves. Notably, SSB remains high enough to produce an above average year class if other environmental conditions (e.g., cool, wet winters in the major spawning areas) align to support young-of-the-year survival.

What is the outlook for the stock to rebuild by 2029?

Striped bass were declared overfished in 2019 and are thus under a rebuilding plan with the goal of reaching the SSB target by 2029. Model-based projections are used to predict what will happen to SSB and abundance after the last year included in a stock assessment and inform the rebuilding plan. Projections require assumptions to be made about future conditions (e.g., fishery catch, year-class strength), and are thus inherently uncertain—especially the further out you look. Projections can also change when subsequently re-run with realized data replacing any of the assumptions. Projections tend to be viewed in the context of their probability, with a 50% probability being a general statistical standard. For example, we’ll talk about the level of striped bass fishery removals (harvest plus discards) that are projected to lead to a 50% probability that SSB will be above its target (and thus rebuilt) in 2029. Aiming for a higher probability is a mechanism for a management plan to be more risk adverse, or conservative, as a policy decision.

The most recent projections provided by the ASMFC Striped Bass Technical Committee in July 2025 indicate that the current management measures have a 30% probability of leading to a rebuilt stock in which SSB exceeds the target level in 2029, and that a 12% reduction in fishery removals would be needed in 2026 to convert that to the standard 50% probability. At the request of the Management Board, the Technical Committee also provided a projection to achieve a 60% probability of being rebuilt by 2029, in recognition of the importance of the striped bass fishery along the coast. That projection indicated that a 18% reduction in total fishery removals would be needed in 2026 to achieve the 60% probability. These projections use final estimates of recreational fishery removals in 2024 and preliminary estimates of commercial fishery removals in 2024 to estimate F in 2024, and then make assumptions about how F will change compared to 2024 for the out years (more on this below).

These projections assume that juvenile recruitment in future years will be similar to that from the last 15 years. This is a cautious assumption because recruitment in the 20 years prior to that was generally higher. However, the last few years have had some of the lowest recruitment estimates since the stock was last considered overfished in the 1980s. Consequently, the Striped Bass Management Board also asked for projections that assume future recruitment is similar to just the past few years, to better understand the sensitivity of the results to changes in recruitment. These projections call for slightly higher levels of fishery reductions in 2026 to achieve the 50% and 60% rebuilding probabilities. Longer-term projections (out to 2035) using this very low recruitment assumption predict that SSB will begin to decline again shortly after 2029.

All of these projections assume that fishing mortality will increase somewhat in 2025—as the above average 2018 year-class ages into the 28-31" coastal recreational slot limit—and then decrease to a level similar to 2024 for the remaining years of the projection (i.e., 2026–2029). The Technical Committee thinks this is the most likely scenario based on what happened when the 2015 year-class aged into the recreational slot limit in 2022 causing an increase in harvest, and the fact that all the year-classes following 2018 have been below average. However, fishing mortality is influenced by many other factors, such as angler effort and fish distribution, so it’s important to remember that projections are informed yet imperfect speculations. Anglers can help minimize the predicted increase in F in 2025 by practicing good stewardship of the resource. DMF has created videos to help you improve your boat, kayak, and surf fishing for striped bass while also teaching you how to maximize the survival of fish returned to the water.

Will striped bass regulations change as a result of the 2024 Stock Assessment?

Regulations will possibly change in 2026. The Striped Bass Management Board initiated Draft Addendum III in December 2024 to consider additional measures to reduce fishery removals in 2026 if needed to support stock rebuilding. Since then, the Management Board has met several times to provide additional direction on the range of alternatives for development (including some outside the scope of rebuilding). In August 2025, the Management Board approved Draft Addendum III for public comment. Public hearings are occurring coastwide throughout the month of September (see below for more information). Final action on the addendum is scheduled to take place in October at the ASMFC Annual Meeting, such that the selected measures can be implemented by the states in time for the 2026 fishing season.

Draft Addendum III considers four main management topics:

- Changing the recreational and commercial management measures to achieve a 12% reduction in fishery removals to increase the probability of achieving a rebuilt stock in 2029 from 30% to 50%.

- Modifying the coastwide commercial tagging program to require point-of-harvest tagging.

- Standardizing the method for measuring the total length of a striped bass for compliance with size limits.

- Modifying the recreational fishing season in Maryland’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay to increase fishing access without increasing fishery removals.

Each of these topics is explored in more detail in subsequent questions below.

Please note that striped bass management measures have not changed for 2025. Initially after reviewing the 2024 Stock Assessment in October 2024, the Striped Bass Management Board considered taking an expedited action to adjust measures for 2025 to lessen the predicted increase in fishing mortality from the 2018 year-class entering the ocean recreational slot limit this year. This would have required the Management Board to select the additional management measures without the benefit of a dedicated public comment period. Additionally, the Board was still waiting on full year (albeit preliminary) 2024 fishery data to understand the effect of the last round of new measures implemented under Addendum II. (See our previously published FAQ on Addendum II for more information.) Consequently, a majority of the Management Board instead voted to initiate Draft Addendum III to consider management revisions for 2026 in a manner inclusive of the 2024 data and robust stakeholder engagement.

If the Management Board takes final action on Draft Addendum III in October 2025 it will also have some preliminary information then on whether fishery removals increased in 2025 as predicted, as well as what to expect from the 2025 year-class. This will likely play into the management decision. The actions of individual anglers can make a difference. Things you can do to support stock rebuilding include keeping only the fish you know you will eat and enjoy, as well as modifying your fishing tactics and tackle to maximize the survival of any catch returned to the water.

What management measures are being considered to reduce fishery removals?

Draft Addendum III considers an overall 12% reduction in fishery removals to support stock rebuilding, with each sector—recreational and commercial—contributing equally. The specific types of management measures proposed to achieve the reduction include: recreational seasons, recreational size limit changes, and commercial quota reductions.

Regarding recreational seasons, the options include two types of closed periods to achieve reductions: no-harvest closures, in which catch-and-release fishing for striped bass is allowed but no striped bass may be retained; and no-targeting closures, in which not just harvest but all fishing for striped bass is prohibited. Neither type of closure has been required by the interstate plan to achieve fishery reductions before (only spawning protections), making this an important issue for public input. Anglers tend to be more familiar with closed seasons that don’t allow for the harvest of a species; during such times they may still enjoy catch-and-release fishing. No-targeting closures are being considered because catch-and-release fishing contributes significantly to the overall mortality of striped bass. While only about one in every 10 striped bass caught and released dies from that interaction, the popularity of fishing for striped bass results in millions of fish being released each year and the number of fish that dies from catch-and-release fishing can equal the number of fish that dies from being harvested. Although no-targeting closures can be shorter than no-harvest closures to achieve the same reduction, these calculations require additional assumptions about angler behavior (i.e., how fishing effort will change), introducing more uncertainty as to the outcome. While viewed by some as more equitable, no-targeting closures come at a worrisome cost to fishing access and with enforcement challenges. Seasons could potentially be applied coastwide, or in a regional approach given how the migratory nature of striped bass affects its seasonal availability along the Atlantic coast.

The draft addendum expresses the closures as a number of days closed per two-month “wave” (i.e., January-February is wave 1, March-April is wave 2, and so on), based on how recreational catch is estimated. Specific calendar dates are not given because there are multiple possibilities for each option. The specific dates for a selected option would be determined by the Management Board during (or very shortly after) final action in October. In general, closed seasons can be shorter if applied during the peak fishing months, or longer if applied during less active months.

Recreational size limit changes are under consideration, with options focused on the Chesapeake Bay fishery and so-called “mode splits” that would provide anglers aboard a for-hire vessel a wider slot limit than anglers fishing from a private vessel or the shore. For-hire operators have advocated for the latter to help keep their businesses solvent. For the coastal recreational fishery, the current narrow slot limit (28-31") results in few options to further reduce recreational fishery removals. Early in the draft addendum’s development, the Striped Bass Management Board decided not to go in the direction of any slot limits narrower than 3 inches, nor to target fish below the current 28" minimum (which the Technical Committee advised against as a biological risk given the predominance of immature fish, estimated increase in harvest, and loss of spawning potential for the stock). The resulting options to achieve reductions would necessitate moving to a 3-inch slot on much larger striped bass, which the Management Board also decided against considering. Accordingly, the only size limit change considered for the ocean recreational fishery is a wider slot limit for the for-hire mode (28-33”), which would require a 13% reduction achieved through a longer seasonal closure for all anglers. In the Chesapeake Bay, the current slot limit is wider (19-24") leaving more room for a size limit change to achieve the reduction without any change to the season. Options include a 20-23” slot for all modes, or a mode split option of 19-22” for private/shore and 19-25” for for-hire.

What are the implications for a commercial harvester tagging requirement in Massachusetts?

Each state with a commercial striped bass fishery has been required to have a commercial tagging program (in which all commercially harvested striped bass are tagged with single-use, traceable tag) since 2014 as a measure to limit illegal harvest. Importantly, the interstate management plan gave states the flexibility to implement either a point-of-harvest or point-of-sale tagging program (i.e., tagging is done by the harvester or the primary buyer), in consideration of the differences between the states’ fisheries and the administrative cost on state agencies. Notably, only those states with limited-entry permits and individual fisherman quotas (IFQs) for striped bass have implemented point-of-harvest tagging programs. Massachusetts implemented commercial tagging at the point-of-sale.

As a point-of-sale tagging state, DMF distributes and accounts for tags that are issued to roughly 125 primary buyers of striped bass each year. Tags are made available to each dealer based on their history of striped bass purchases, with supplemental tag requests fulfilled upon verification of tag use in weekly dealer reporting. At the end of each season, each dealer submits a report of their tag use, returns unused tags, and accounts for any missing tags. Generally, less than 1% of issued tags are unaccounted for in Massachusetts.

Massachusetts took this approach because a point-of-harvest tagging program would have required significant modification to the nature of the state’s commercial fishery or insurmountable administrative costs. The Massachusetts commercial striped bass fishery is relatively unique in that DMF has been able to successfully manage it as an open entry fishery in which there are minimal barriers to obtaining a permit. Most other states’ commercial striped bass fisheries (and most other commercial fisheries in Massachusetts) are limited entry, meaning that permits are only available as renewals or through costly business transactions. This results in a large number of commercial striped bass permits being issued each year—generally between 4000 and 5000—although only about a quarter of them report any commercial sales. It would be extremely challenging for DMF to implement a point-of-harvest tagging program in which tags would have to be distributed and accounted for across thousands of permit holders. Instead, DMF may need to enact a limited entry scheme thereby changing the open access feature of the fishery, and then reduce the number of permit holders to a fraction of the number we have today.

Why is the method of measuring a striped bass being considered for revision?

The interstate plan for striped bass establishes all size limits in total length, but does not explicitly define how total length is measured, resulting in variation among the states. DMF recently modified its own definition of striped bass total length (see figure) after discovering that how the tail is oriented—pinched or fanned out—can affect the measured length by over an inch, which undermines the intended conservation of size limits. DMF brought this to the attention of the Striped Bass Management Board and asked for Draft Addendum III to consider standardizing the method of measurement to ensure clarity and consistency among states.

What is the Maryland seasonal proposal all about?

Maryland requested the addition of an option in Draft Addendum III to revise its recreational fishing seasons for striped bass in the Chesapeake Bay in a manner not expected to increase fishery removals. Such types of individual state proposals are generally pursued through an allowance in interstate management plans for “conservation equivalency” or CE, in which a state can propose to deviate from a plan requirement to address state specific needs in a manner that is deemed to achieve the same quantified level of conservation. However, the interstate management plan for striped bass does not allow states to submit CE proposals for non quota-managed fisheries while the stock is overfished (in support of the coastwide rebuilding measures), thus Maryland is unable to submit a CE proposal until a stock assessment indicates that spawning stock biomass is above the threshold level. Instead, Maryland is pursuing the other allowed approach to revise its season, which is to incorporate it into an Addendum (or Amendment) to the management plan. This results in additional scrutiny of Maryland’s seasonal proposal, including coastwide public comment through the Addendum process.

Maryland’s stated objective is to simplify its regulations, re-align access to support their anglers’ needs, and adjust seasons to better consider updated data regarding discard mortality under varying conditions (see figure). Were this change supported by the Striped Bass Management Board, the revised season would provide the baseline to which any additional seasonal closures proposed in Draft Addendum III would be applied.

The Striped Bass Management Board has included in Draft Addendum III a sub-option for an “uncertainty buffer” on Maryland’s proposed season, such as would be required were it submitted as a CE proposal. The striped bass plan requires an uncertainty buffer be applied to CE proposals that deal with non-quota managed fisheries as well as when using imprecise recreational data, to increase the alternative measures’ probability of success in achieving equivalency with the FMP standard (which in this case is the seasons in place in Maryland in 2022). The sub-option is for a 10% uncertainty buffer, which would result in more days being closed in Maryland.

How can the public review and comment on Draft Addendum III?

Draft Addendum III was approved for public comment in August 2025. The document and all the details needed to submit comment—whether online, in writing, or at a public hearing—are available at the ASMFC Action Tracker for Striped Bass Draft Addendum III. Seventeen public hearings in venues across the coast or online are occurring throughout the month of September. Massachusetts will host two public hearings on September 25 (Woburn) and September 30 (Bourne). Both of the MA hearings have a listen-only option for those unable to attend in-person (after which written comment could be submitted). There is also a general public hearing webinar on September 30 (registration link) and members of the public may also attend any other states’ hearings (some of which have a virtual participation option). If you can’t attend any of the hearings, there is a recording of the presentation on the ASMFC’s YouTube channel and comments can be submitted electronically in writing by email or a public comment form. All written comments are due October 3, 2025.

Contact

Online

Fax

| Last updated: | September 17, 2025 |

|---|