- Scientific name: Lupinus perennis L.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Image credit: Paul Somers

Wild lupine, Lupinus perennis, is a short-lived perennial in the pea family (Fabaceae). It can grow up to 0.6 m (two feet) high but is often shorter. It has alternate compound palmate leaves, usually with seven to eleven oblanceolate leaflets. It produces a terminal flowering spike consisting of blue (rarely white or pink) bilaterally symmetrical pea-shaped flowers that bloom in late spring and early summer. The fruits are pubescent pods or legumes (30-50 mm [1.18-2 in] long by 8-10 mm [0.31-0.39 in] wide) which split open when ripe to release 2 to 4 seeds.

The non-native garden lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus) may be confused with wild lupine. The garden lupine can be up to 1 m [3.3 ft] in height and has ten to eighteen leaflets per leaf. It is planted or often escapes from gardens to roadsides in New England. Its flowers range in color from blue to pink to white.

Life cycle and behavior

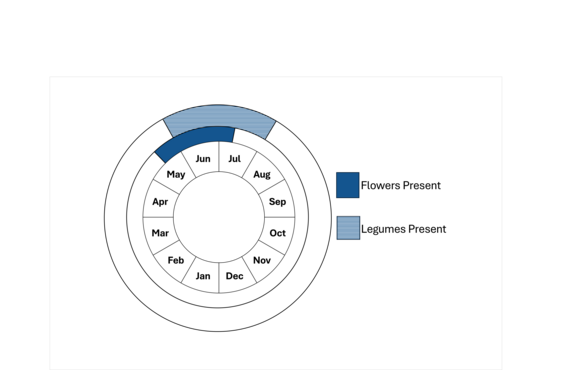

Wild lupine is a short-lived perennial plant. It flowers mid-May to the first week of July, producing ripe seeds through June and July. The seed must be scarified (weakening, opening, or otherwise softening the seed coat) and overwinter before it will sprout. This may happen naturally if the plant is browsed, within an animal’s stomach or it may occur by being blown across a sandy surface. Once the plant has sprouted the following spring, it will take a year or two before it blooms if it is in a sunny habitat.

Population status

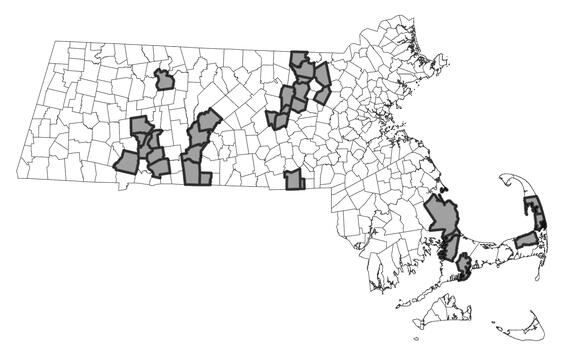

In Massachusetts, wild lupine was found historically in Berkshire County at one site, but the rest of the current and historic records are from the Connecticut River valley eastward. There are current reports from Franklin, Hampshire, Hampden, Worcester, Middlesex, Plymouth, and Bristol Counties. There are historic records from Essex and Nantucket counties, but no current records, and no records either current or historic from Suffolk or Dukes counties. Of the 159 documented sites, 53 have been observed since 1999.

Distribution and abundance

Wild lupine has occurred from Maine to Minnesota and south to Florida and Texas. It is critically imperiled in Iowa, Mississippi and West Virginia; and is of concern in several other states. In New England, it is presumed extirpated from Maine, critically imperiled in Vermont and imperiled in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island. Connecticut has not assessed it.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Wild lupine grows in dry, sandy, open fields and woodland clearings, including pitch pine-scrub oak barrens and sandplain grass communities. This habitat may include roadsides, gravel and sand pits, waste areas, and railroad lines, among other disturbed areas. Associated species include little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia), stiff aster (Ionactis linariifolia), bush clovers (Lespedeza spp.), and goldenrods (Solidago spp.), among other plants common in open areas. Edaphic features that are well drained and slightly-to-moderately acidic (Curtis, 1959, Zaremba & Pickering, 1994) appear to be a key feature of sites that support Lupinus perennis. Surface soil disturbance also appears to play an important role in the germination of Lupinus perennis seed (Leach, 1993). Open canopy conditions are important for Lupinus perennis, with minimum canopy cover being an optimal situation (Greenfield 1997, Smallidge et al. 1996, Smith 2002). Conversely, a closing canopy has been shown to greatly reduce or eliminate Lupinus perennis (Grundel et. al. 1998, Grigore et. al. 1996, Hack 1993).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The primary threats to wild lupine are direct destruction of habitat by all forms of development and succession of open habitats to forests, often because of fire exclusion. Once widespread in central and eastern Massachusetts, wild lupine is now much reduced in locations and population sizes. Often, open areas are kept open by mowing, which may not kill the lupine plants outright, but may prevent flowering or seed ripening. Invasive species may also overtake its habitat and shade and out-compete wild lupine plants. White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) will browse on plants; and depredation of wild lupine seed by mice (Peromyscus spp.) has also been shown to be a limiting factor in some occurrences, especially occurrences that have a buildup of leaf litter due to fire suppression. Incompatible mowing practices that prevent wild lupine from setting seed can be an important limiting factor, especially in less natural occurrences such as airfields and cemeteries. Finally, inadvertent impacts from herbicide application can also play an important role in reducing or eliminating wild lupine occurrences, especially those in managed areas such as transmission rights-of-way and roadsides.

Conservation

All current sites and some historical sites where appropriate habitats still exist, should be resurveyed to assess the current populations. Each plant of wild lupine is an individual genet. The best time to complete surveys for this species is when the plants are in bloom, mid-May to the first week of July.

Wild lupine responds very well to active management, as observed at several managed occurrences in Massachusetts. Objectives for active management should include the development of management strategies for each occurrence on protected conservation land, as well as for unprotected occurrences that are deemed to either be a high priority or to have willing landowners. From this group, a subset of sites, based upon priority and opportunity, should be chosen for implementation of management. Ideally, two to three sites from the three major population centers (Cape Cod, Connecticut River Valley, and the Nashua River Valley), as well as at least one site in important peripheral areas, should be initiated. In many cases, the management of wild lupine can or will coincide with other rare species management, such as frosted elfin (Callophrys irus, Special Concern) or a larger natural community management initiative, especially on state-owned barrens natural communities.

Wild lupine seed is relatively easy to collect and relatively easy to germinate, and in certain cases, establishment, augmentation or reintroduction can play an important role in the conservation of this species in Massachusetts. Augmentation may be appropriate at occurrences where the site is protected and management is likely, but the current population is low. Depending on the current size of the population, augmentation should be done with seed from the actual occurrence or supplemented with seed from other occurrences in the immediate area.

Reintroduction may be appropriate for historic occurrences at protected sites where management is likely and there is a nearby extant population to collect seed from. Establishment may be appropriate at large protected sites with appropriate habitat that will be actively managed. Origin may be slightly less restrictive in establishment situations, but material still should be collected from sources at least within the same major watershed.

All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal, seed collection, reintroduction) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

Contact

| Date published: | April 30, 2025 |

|---|