- Scientific name: Lythrum alatum Pursh

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Winged loosestrife is an upright, flowering herb, up to 1 m (~3 ft) tall. Overall, the plant is slender and about halfway up the stem, it often splits into several narrow flowering stems, also entirely upright. When in flower, these display a half dozen to a dozen brightly colored light purple or lavender flowers that are 1 cm (0.4 in) across, consisting of 6 petals and a calyx tube that is about 1 cm (0.4 in) in length. The flowers are solo or paired in the axils of the upper leaves which are smaller than the lower stem leaves and may look like bracts. The leaves are green, sessile, linear-oblong, lance-ovate, or lanceolate, with the lowest opposite each other and the upper leaves alternate. The larger leaves are 4 cm (1.6 in) in length and 1 cm (0.4 in) wide. The leaves become smaller toward the top of the plant.

The stem is 4-angled, meaning it has subtle but clearly apparent thin raised “wings” about 1 mm (0.04 in) in height running the same direction as the stem, giving it the name “winged loosestrife.” The closely related and highly invasive purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) does not have winged stems, and it flowers in a terminal spike with all the flowers together, not separated by short stem segments as is the case with winged loosestrife. Finally, the invasive species has only opposite leaves, unlike winged loosestrife.

Life cycle and behavior

This is an herbaceous perennial that will bloom every year if the habitat conditions are maintained.

Population status

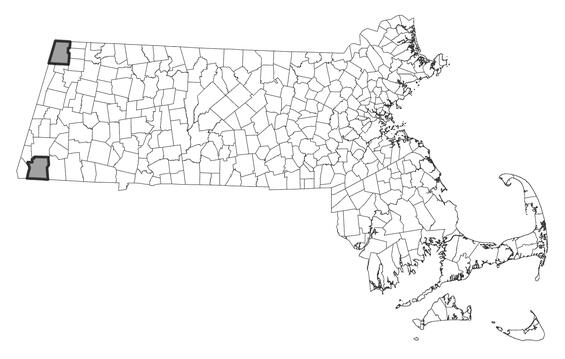

Herbarium specimen records in Massachusetts occur in the eight counties north and west of Plymouth and Bristol counties, except Hampden County. Two-thirds of these occurred prior to 1921 (Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria 2025). The MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP) has 6 records from 3 counties: Berkshire, Franklin, and Middlesex. In a 3000-hour fieldwork survey of all 26 towns in Franklin County over the prior decade, where winged loosestrife was previously known from 3 towns, the species was not found at all (Bertin et al 2020). Only 2 of these records have been observed within the last 25 years, both in Berkshire County. One population in Sheffield was discovered following meadow restoration efforts funding in part by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife restoration grant program. Removal of invasive shrubs allowed over 100 plants to come into bloom. The other population is small with only 10 plants.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Distribution and abundance

Lythrum alatum is common throughout the Midwest and Southeast but rare in the Northeast. In the Atlantic coast region of VA, WV, DL, MD, NJ, PA, NY, and the 6 New England states, there are very few records either historically or currently on iNaturalist, and it is ranked imperiled or critically imperiled in seven states by NatureServe (2025). In fact, Maine and New Hampshire have no iNaturalist records (iNaturalist 2025). In Vermont, it had become state historic with no populations known since 1979. Then in 2017, 38 years later, it was discovered by accident in a new location (Zind 2017).

Habitat

Currently the known locations are in calcium rich, groundwater fed wet meadows that are maintained as open habitats. Formerly some sites were grazed by livestock which kept them open.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

In some areas, it’s clear that invasive and native shrubs have taken over former pastures and hay meadows. Several Eurasian bush honeysuckle species and one hybrid (Lonicera spp., and Lonicera X bella) and two species of buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica and Frangula alnus), as well as giant reed grass (Phragmites australis) and purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) have all been very destructive to freshwater wetlands in New England, crowding out and shading out native species and changing soil conditions. Additionally, hydrologic alterations such as ditching and draining have greatly altered soil conditions for wetlands by drying them out. Beaver dams have done the same, though instead making sites far too wet or below water. A perhaps unexpected threat comes from attempt to control purple loosestrife using beetles from Europe that feed on them. Katovich et al. found that the “Presence of Galerucella spp. on winged loosestrife resulted in a 31% reduction of seed capsules in 1 of 2 yr of study.”

Conservation

Four de novo surveys were completed in 2022, and no plants were found (Harper 2023). Yet that leaves many target locations as potential survey sites. More targeted surveys are needed to find new locations of winged loosestrife, especially in areas of habitat management in the Berkshire region. Since little is known about this species in Massachusetts, surveys of the two extant sites should occur on an annual basis until a greater understanding of the populations and management needs is gained.

Since one management project has been highly successful, more of the same approach should take place in more locations and on greater acreage. Treatment of invasives is an essential part of management for this species.

Galerucella beetles were released in the U.S. years ago to control the invasive purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). Since it is not yet known conclusively whether these beetles will also be detrimental to winged loosestrife, that is an area where active research should take place. Seed germination studies are needed, and ex situ conservation should be explored.

References

Bertin, R. I., M. G. Hickler, K. B. Searcy, G. Motzkin, and P. P. Grima. 2020. Vascular Flora of Franklin County, Massachusetts. New England Botanical Club. 390 pp.

Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria. 2025. Herbarium records. https://portal.neherbaria.org/portal/collections/list.php. Accessed 27 March 2025

Cullina M, Connolly B, Sorrie B, Somers P (2011) The vascular plants of Massachusetts: a county checklist, 1st revision. Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany, Eighth (Centennial) Edition—Illustrated. American Book Company, New York.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines A (2011) New England Wild Flower Society’s Flora Novae Angliae: a manual for the identification of native and naturalized higher vascular plants of New England. Yale University Press. 1008 pp.

Harper, Lynn. 2023. Species listing proposal for Lythrum alatum. Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species. Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA.

iNaturalist 2025. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. Accessed 27 March 2025.

Katovich, E. J. S., R. L. Becker, D. W. Ragsdale, and L. C. Skinner. 2008. Growth and Phenology of Three Lythraceae Species in Relation to Feeding by Galerucella calmariensis and Galerucella pusilla: Predicting Ecological Host Range from Laboratory Host Range Testing. Invasive Plant Science and Management 1: 207–215.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 3/19/2025

Zind, S. 2017. Rare Flower Thought Extinct in Vermont, Rediscovered. Vermont Public. Website https://www.vermontpublic.org/vpr-news/2017-07-28/rare-flower-thought-extinct-in-vermont-rediscovered [accessed 27 March 2025].

Contact

| Date published: | May 6, 2025 |

|---|