- Scientific name: Glyptemys insculpta

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Under Review (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

The wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) is seldom found far from cool, clear streams, and is more commonly encountered in central and western Massachusetts. The wood turtle is a medium-sized freshwater turtle(14–20 cm; 5.5–8 in) recognized by orange coloration on the legs and neck. The carapace (upper shell) is usually rough and sculpted, with a “woodworked” appearance, and each scute rises upwards in an irregularly shaped pyramid of grooves and ridges. The carapace is oval- to egg-shaped, brown, tan, or grayish-brown, with a midline ridge (or ‘keel’). The larger scutes of the carapace are often patterned with black and yellowish markings. The plastron (lower shell) is cream to yellow with irregular dark patches on each scute’s outer, posterior corner. The head is black, but the beak and chin are streaked with yellow or gray. In Massachusetts, the forelegs are a rich orange-red with black outer scales. Males have an oval, concave shape to their plastron, a thick and long tail, and a broader and more robust head than females. Hatchlings have a dull-colored shell that is broad and low, a tail that is almost as long as their carapace, and neck and legs that lack orange coloration.

Similar species: The wood turtle is distinctive in its combination of a typically brown shell, orange front limbs, and plastron fused solidly to the carapace by a bony “bridge.” Wood turtles could confused with eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina) or Blanding’s turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) where they overlap with one or the other, such as the southern Connecticut River Valley and the I-495 beltway. However, both of these species have a moveable plastron. Eastern box turtles are smaller than wood turtles and have a hinged plastron that allows them to completely enclose their limbs and head when threatened. Further, while young Blanding’s turtles can have a shell that appears “sculpted,” their throat is bright yellow and they lack the typical orange forelimb coloration of the wood turtle. Wood turtles could be confused with bog turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) and, in fact, the two species are closely related. But bog turtles are exceedingly rare and only found in Berkshire County, and they have a distinctive orange “blotch” on the side of the head. The northern diamond-backed terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) can be similar in size and shape to the wood turtle, buts its strict association with estuaries means these two species rarely overlap in Massachusetts at the present moment. Additionally, the terrapin’s skin is greyish to white and not orange.

Life cycle and behavior

Wood turtles overwinter in flowing rivers and perennial streams and rarely in small beaver impoundments. Wood turtle activity in the stream slows to a near-halt by mid-November, but some movements may continue to occur within the stream during the winter season. Wood turtles overwinter (or “brumate”) alone or in small groups. Historically, when densities were higher, large winter aggregations were probably common. However, extended periods of surface activity or emergence from the water do not occur again until mid-March or early April. In spring, wood turtles use sand, clay, or mud banks to bask in the spring sun. During the active season from April to October, wood turtles are usually encountered within a few hundred meters of the stream banks. They have relatively linear home ranges that often exceed 1 km (0.6 mi) or more. Occasionally, adults will move overland between adjacent basins; these overland movements can exceed 15 km (9.3 mi).

Wood turtles forage in early successional fields, hayfields, and forests throughout the active season, moving farther from the stream until reaching their maximum distance in July and August. Wood turtles are opportunistic omnivores; they feed readily on both plant and animal material found on land or in the water. The wood turtle occasionally exhibits a remarkable feeding behavior referred to as ‘worm stomping,” in which they will stomp on the ground, alternating their front feet to create vibrations in the ground that mimic rainfall. Earthworms (and possibly other invertebrates) respond, coming to the ground’s surface and are promptly devoured. This behavior was first reported in captive wood turtles but has since been observed throughout the species’ range (including Massachusetts).

Wood turtles mate in the water but the female turtle will occasionally drag the male onto a shallow beach. Courtship on land has been documented. Wood turtles mate opportunistically throughout their activity period whenever both sexes are in the stream or river, but autumn is peak courtship and mating season in New England. Males exhibit aggressive behavior such as chasing, biting, and shell-thumping during the mating season. Nesting in Massachusetts occurs over a four-week period, primarily in June. Nesting sites are often a limited resource for wood turtles in Massachusetts, in part because their streams have been hardened and channelized and natural instream nesting features are rare. Females will nest on instream point bars and beaches when they are available, but they will travel long distances up to 600 m (2000') from the river if there is no suitable habitat near the floodplain. Wood turtles often make multiple nesting attempts or “false nests” before selecting a final site to lay eggs. Female wood turtles lay one clutch a year, and several females may use the same exposed nesting area year after year. Clutch size in Massachusetts averages 7 eggs. Hatchling emergence occurs from August through September. The life span of the adult wood turtle exceeds 50 years, and generation time probably exceeds 30 years in some Massachusetts populations.

Population status

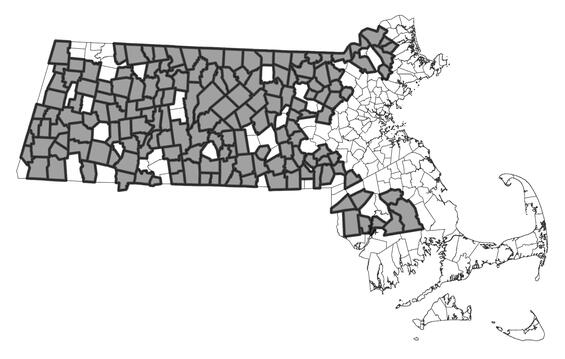

Wood turtles appear to be in severe decline across much of their northeastern range. Partners from New Brunswick to Virginia collaborated on a range wide status assessment and published an article (Willey et al. 2022) detailing the habitat loss and fragmentation of the wood turtle. They found that 58.1% of the modeled suitable habitat in the Northeast is potentially impaired by landscape development. Much of eastern Massachusetts, corresponding approximately to I-495, has become unsuitable for wood turtles (although there are a few remaining populations inside the I-495 beltway). Most of the larger and more connected populations are found in the central and western regions of the state. A large population of wood turtles in Massachusetts will typically number less than 100 adults. Many occurrences number fewer than 10–20 turtles. However, evidence from the 1850s suggests that wood turtles were far more abundant in central Massachusetts than at present.

Distribution

The wood turtle can be found throughout interior New England, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, west to eastern Minnesota, and south to northern Virginia and West Virginia. The wood turtle was historically widespread in Massachusetts, but populations in urbanized areas in the eastern part of the state are severely impaired. The wood turtle is not known from any islands.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Wood turtles are strongly associated with small- to mid-sized perennial streams, often with a noticeable current. Slower-moving mid-sized streams are favored, with clay, sand, gravel, or cobble substrate and heavily vegetated, but open-canopy, riparian areas. Undercut banks, large tree root masses, deep pools, and debris dams provide hibernating sites for overwintering. Open areas with sand or gravel substrate near the stream edge are used for nesting. Wood turtles spend most of the spring and summer in riparian clearings, wetlands, forested uplands, and fields (including hayfields and pastures). Wood turtles return to the streams by early fall but remain active into November in most years, especially as average fall and winter temperatures continue to rise each year.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Hatchling and juvenile survival are typically low, and it takes more than a decade for a wood turtle to reach sexual maturity. Adult longevity and reproductive windows lasting several decades compensate for low annual reproductive rates. Adult survivorship must be very high to sustain a viable population. These characteristics make wood turtles vulnerable to human disturbances. Population declines of wood turtles are likely caused by roadkill associated with roads near wooded streams, hay-mowing operations and other agricultural activities, incidental collection of specimens for pets, unnaturally inflated rates of predation in suburban and urban areas, forestry during the active season, and pollution of streams. Climate change further exacerbates these threats (Staudinger et al. 2024) by increasing stream temperatures and changing summer thermal regimes, which affect turtle nesting behavior and phenology. These changes reduce nesting success, alter precipitation patterns that affect wetland water levels, and impact turtle foraging and overwintering habitat. Extreme storm events can also flood nests, damage turtle habitat, and increase mortality rates by displacing turtles downstream.

Conservation

Cooperative conservation planning with adjacent northeastern states dates to 2009. The 13 northeastern states, through the “Regional Conservation Needs” program managed by the Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (NEAFWA), collaborated on a status assessment in 2015 and a conservation plan in 2018. The northeastern states agreed to a standardized protocol for searching for wood turtles and undertook range-wide genetics sampling to identify conservation and management units. They identified "focal core areas" and "management opportunities" in each state from Maine to Virginia in order to prioritize limited resources and direct federal funds. Needed management actions are tracked at the site- and basin-level. The regional conservation plan for the wood turtle in the northeastern United States is a living document that is updated at regular intervals based on new assessments of population and landscape conditions.

Inventory and monitoring needs in Massachusetts

Ongoing inventory of potential wood turtle habitat is necessary to identify and prioritize areas for conservation. Local naturalists can play a key role in documenting the distribution of this species in Massachusetts by photographing basking turtles and wood turtles killed on roadways. Key areas of data deficiency in Massachusetts include (1) the Hoosic River watershed, (2) the Farmington River watershed, (3) the Taunton River watershed, and (4) coastal basins from Essex to Bristol Counties. Sightings should be reported to MassWildlife’s Heritage Hub with photo documentation. Instructions on how to submit a report on Heritage Hub are provided on the webpage. Regional, standardized monitoring with the northeastern states from Maine to Virginia should continue at 5- to 10-year intervals to track population trends, habitat use, and changes in the landscape. Monitoring should include field surveys, PIT-tagging, and remote-sensing technology. Environmental DNA (eDNA) and drones could prove to be useful and noninvasive methods of demonstrating recent use of specific upland habitat features. Any handling of wood turtles will require a permit from MassWildlife.

Research needs

Scientific research should investigate the factors influencing wood turtle population dynamics and habitat use, as well as the effects of changing precipitation patterns and warming temperatures. Specific research needs include (a) population genetics to assess genetic diversity and connectivity between populations, and studies of relatedness to evaluate dispersal patterns and population structure; (b) studies of dispersal and connectivity to identify important dispersal corridors and assess barriers to movement; (c) studies of effective methods of both stream and upland habitat management, including best practices to reduce mortality during mowing.

Management needs

In agricultural areas and on large parcels with open fields, landowners should consider whether mowing practices can be updated to minimize machine-related mortality between May and October. Late-season mowing of pastures, old fields, and meadows is preferred over late-spring or summer mowing. Edges of fields, especially those with southern exposure or access to water, are often used disproportionately by wood turtles. In general in important wood turtle areas, mowing and heavy machinery use should occur outside of the wood turtle activity season (October 15th–April 15th in the north and November 15th–March 15th in warm years). If mowing during the active season is unavoidable, create unmowed riparian buffers of 30–100 m adjacent to streams. Consider using sickle-bar mowers as they result in lower wood turtle mortality rates than disc and rotary mowers. When it is necessary to use disc and rotary mowers, raise the mower head to 20 cm (8 in) to reduce mortality, and mow fields starting from the edge farthest from the river to allow turtles to move out of harm’s way.

Educational materials are available for partners to highlight the detrimental effects of keeping wood turtles as pets (an illegal activity that reduces reproduction in the population), releasing pet store turtles (which could spread disease), mowing fields and shrubby areas, feeding suburban wildlife (which increases the number of natural predators on turtles), and driving ATVs in nesting areas, especially in June. When safe to do so, people should be encouraged to help wood turtles cross-roads (always in the direction the animal is heading). Wood turtles should never be transported to “better” locations, such as a nearby lake or pond, they will often attempt to return to their original location and likely need to traverse roads to do so. Injured wood turtles should be brought to a licensed turtle rehabilitator or veterinarian. A list of licensed turtle rehabbers in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts are available on the mass.gov webpage: Turtle Veterinarians and Wildlife Clinics or Find a Wildlife rehabilitator.

MassWildlife’s Northeast, Western, Connecticut Valley, and Central Districts oversee Wildlife Management Areas within priority wood turtle sites. MassWildlife should continue to work proactively with the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and key municipalities (especially in the Connecticut River Valley, Worcester County, and Berkshire County) to protect and manage key habitats. Key partners, including Zoo New England, should continue their dedicated site-level conservation programs. Management of high-priority sites should focus on maintaining and enhancing habitat quality. Wetland restoration, creation of nesting habitat, and removal of invasive plants, are some examples of management actions at these high-priority sites.

Wildlife crossing structures, exclusion fencing along roads, and reduced speed limits in key areas could limit many road mortalities. MassWildlife and MassDOT have fostered a strong, ongoing partnership in the planning and regulatory stages to address road mortality. Towns should consider wildlife passage structures for bridge and culvert upgrades and road-widening projects within or near wood turtle streams. MassWildlife should inform local municipalities of key locations where these measures would be most effective for wood turtle conservation. MassWildlife and MassDOT should continue to work collaboratively to minimize the negative effects of roads and highways on key wood turtle populations.

References

Jones, M.T. 2009. Spatial Ecology and Conservation of the wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in Central New England. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts; Amherst.

Jones, M.T., and P.R. Sievert. 2009a. Effects of stochastic flood disturbance on adult wood turtles, Glyptemys insculpta, in Massachusetts. Canadian Field-Naturalist 123: 313–322.

Jones, M.T., and P.R. Sievert. 2009b. Glyptemys insculpta (wood turtle). Diet. Herpetological Review 40: 433–434.

Jones, M.T., and L.L. Willey. 2020. Cross-watershed dispersal and annual movement in adult wood turtles (Glyptemys insculpta). Herpetological Review 51: 208–211.

Jones, M.T., and L.L. Willey. 2021. Biology and Conservation of the wood turtle. Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

Jones, M.T., H.P. Roberts, and L.L. Willey. 2018. Conservation Plan for the wood turtle in the Northeastern United States. Report to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service; Westborough.

Jones, M.T., L.L. Willey, T.S.B. Akre, and P.R. Sievert. 2015. Status and Conservation of the wood turtle in the Northeastern United States. Prepared for the Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

Jones, M.T., L.L. Willey, P.R. Sievert, and A.M. Richmond. 2019. Reassessment of Agassiz’s wood turtle collections reveals significant change in body size and growth rates. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 14: 41–50.

Jones, M.T., L.L. Willey, D.T. Yorks, P.D. Hazelton, and S.L. Johnson. 2020. Passive transport of Eastern Elliptio (Elliptio complanata) by freshwater turtles in New England. Canadian Field- Naturalist 134: 56–59.

Moore, J.F., J. Martin, H. Waddle, E.H.C. Grant, J. Fleming, E. Bohnett, T.S.B. Akre, D.J. Brown, M.T. Jones, J.R. Meck., K. Oxenrider, A. Tur, L.L. Willey, and F. Johnson. 2022. Evaluating the effect of expert elicitation techniques on population status assessment in the face of large uncertainty. Journal of Environmental Management 306:114453.

Mothes, C.C., H.J. Howell, and C.A. Searcy. 2020. Habitat suitability models for the imperiled wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) raise concerns for the species’ persistence under future climate change. Global Ecology and Conservation 24.

Mullin, D.I., R.C. White, A.M. Lentini, R.J. Brooks, K.R. Bériault, and J.D. Litzgus. 2020. Predation and disease limit population recovery following 15 years of headstarting an endangered freshwater turtle. Biological Conservation 245, 108496.

Roberts, H.P., M.T. Jones, L.L. Willey, T.S.B. Akre, P.R. Sievert, P. deMaynadier, K.D. Gipe, G. Johnson, J. Kleopfer, M. Marchand, J. Megyesy, S. Parren, E. Thompson, C. Urban, D. Yorks, B. Zarate, L. Erb, A.M. Ross, J. Dragon, L. Johnson, E. Lassiter, and E. Lassiter. 2021. Large-scale collaboration reveals landscape-level effects of land-use on turtle demography. Global Ecology and Conservation 30: e01759.

Robillard, A.J., S. Robinson, E. Bastiaans, and D. Vogler. 2019. Impacts of a highway on the population genetic structure of a threatened freshwater turtle (Glyptemys insculpta). Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 13(2): 267–275.

Willey, L.L., M.T. Jones, P.R. Sievert, T.S. Akre, M. Marchand, P. deMaynadier, D. Yorks, J. Mays, J. Dragon, L. Erb, B. Zarate, et al. 2022. Distribution models combined with standardized surveys reveal widespread habitat loss in a threatened turtle species. Biological Conservation 266: 109437.

Contact

| Date published: | March 10, 2025 |

|---|