- Scientific name: Emydoidea blandingii

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Adult female Blanding’s turtle, showing the characteristic yellow throat, streaked upper jaw, and spotted carapace.

Massachusetts populations of Blanding’s turtle (Emydoidea blandingii)are part of a small, relict occurrence in central New England that extends into New Hampshire and Maine. Its core range is hundreds of miles farther west, in the Upper Midwest, Great Lakes, and northern prairies. The species is named for William Blanding, a Massachusetts-born physician and naturalist from Rehoboth, who discovered the first described specimens near Chicago, Illinois. In Massachusetts, Blanding’s turtle is most likely to be encountered in the northeastern counties (in a broad arc from about Worcester to Merrimac) although a few populations persist south and east of the Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90). Blanding’s turtles are medium-sized (slightly larger than a wood turtle, Glyptemys insculpta) with a domed shell and striking yellow throat. The carapace or upper shell is dark gray and marked with spots or vermiculation (worm-like markings). Individual Blanding’s turtles can have either a speckled or spotted appearance. The plastron or lower shell is not fused to the carapace; rather, it is kinetic and slightly moveable and there is no bony bridge connecting the plastron to the carapace as there is in the wood turtle. However, the plastron does not close tightly like a box turtle. Blanding’s turtle’s plastron usually has a cream- or horn-colored background with blackish blotches on each of 12 plastral (belly) scutes. This species is sexually dimorphic and slightly dichromatic, meaning that males and females are shaped and colored differently. Males are larger and have longer, thicker tails, a slightly concave plastron, and a dark upper lip (or tomia). Females and juveniles have a streaked upper lip. Hatchling Blanding’s turtles have a brown or olive-colored carapace and dark-colored plastron with light-colored margin, and range between 3.4–3.7 cm (1.3–1.5 in) in length. Adults range from 16–22 cm (6–9 in) in shell length. Blanding’s turtle overall appearance is dark, highly domed, and smooth, and the yellow throat is often prominently displayed when basking.

Similar species: Blanding’s turtle can usually be differentiated from all other native turtles by its solid-yellow throat and domed, smooth shell. However, various life stages of Blanding’s turtle could be confused with any of the co-occurring species in the subfamily Emydinae, including eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina), which may have yellow on their chin but lack the yellow throat and neck characteristic of Blanding's turtle. Also, box turtles are much less massive than Blanding’s turtle, and their carapace has a prominent midline ridge or keel. Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) are also much smaller than Blanding's turtles and have distinct, round, bright-yellow spots on a black carapace—spotted forms of Blanding’s turtles usually have paler yellow or whitish markings. Painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) are far more abundant than Blanding’s turtles and have a more flattened overall appearance and a glossy black shell, with a dark head with yellow stripes, and red and yellow markings around the edge of the carapace. Blanding’s turtles are sometimes confused with common sliders (Trachemys scripta), which can be locally common in urban parks and ponds and waterways near Boston. Sliders usually have prominent stripes on their face and limbs and a serrated rear carapace margin, but there are melanistic (dark-pigmented) forms that create confusion when viewed from a distance. Blanding’s turtle is more commonly a species of remote shrub swamps and vast marshlands, while sliders are currently more common in urbanized waterways and ponds.

Life cycle and behavior

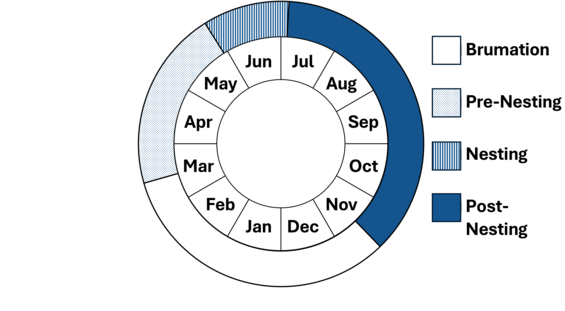

Blanding's turtles are long-lived, with individuals documented to reach ages over 80 years in Michigan. Like most freshwater turtles in Massachusetts, Blanding’s turtles are active from April to October in most years, with occasional activity in March and November in warm years, and overwinter (or brumate) in permanent wetlands or deep vernal pools from November through March. Upon emergence from brumation, many Blanding's turtles leave their overwintering ponds and move overland to vernal pools, grassy wetlands, shrub swamps, and kettle ponds, where they feed and mate and bask. Blanding's turtles are omnivores, eating both animal and plant material, and unlike box turtles and wood turtles they generally feed in the water. Their documented animal food items include snails, crayfish, earthworms, insects, small fish, and carrion. Blanding's turtles also eat a variety of plants including coontail, duckweed, bulrushes, and sedges.

Blanding’s turtles court and mate underwater in marshes, ponds, and vernal pools from April to August. During mating, Blanding's turtles exhibit a variety of behaviors during mating including chasing, mounting, and head-swaying. Blanding’s turtles nest in upland cleared areas from late May to early July. Female Blanding's turtles reach sexual maturity at 14–20 years and may travel overland more than 1 km (0.62 mi), to find appropriate nesting habitat. Like most other freshwater turtles in Massachusetts (except the bog turtle and wood turtle), Blanding's turtles exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD): eggs incubated at cooler temperatures tend to produce males, and higher temperatures produce females. Clutch sizes range from about 8–12 eggs, but larger clutches are frequently reported. Like wood turtles, eastern box turtles, and spotted turtles, hatchling Blanding’s turtles emerge in late August and September.

Population status

Blanding's turtles in Massachusetts are listed as Threatened under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA) and are currently (2025) under review for federal Threatened status under the Endangered Species Act. Populations of Blanding’s turtle in Massachusetts are typically small and number fewer than 50 individuals (although several larger populations are known). Population density varies depending on habitat quality and landscape context. Reported densities in New England range from 0.01 to 0.1 turtles per hectare (2.5 ac) of suitable habitat. However, densities as high as 0.5 turtles per hectare have been reported in some areas. Between 2012–2013, 41 sites were sampled in Massachusetts, an effort that resulted in 5,413 trap-nights and 634 Blanding's turtles captured. In addition to trapping, 19 sites were visually surveyed. A total of 177 Blanding's turtles were observed during these surveys.

Distribution and abundance

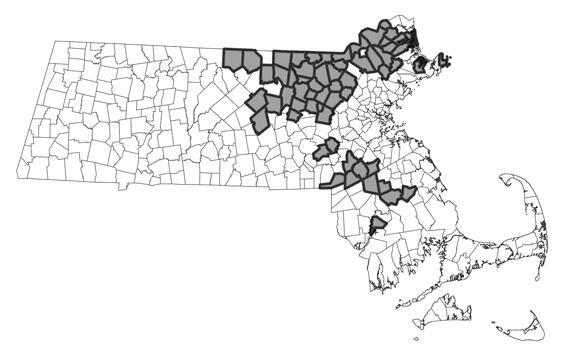

Blanding's turtle is very widely distributed across temperate latitudes in North America from western Nebraska to southern Nova Scotia, but its populations are frequently isolated and fragmented. Massachusetts populations of Blanding’s turtles are concentrated in Essex, Middlesex, northern Worcester, and Norfolk Counties. There are some outlying populations in adjacent counties, and historical records closer to Boston suggest a slightly wider distribution in the past. In New England, Blanding’s turtles occur in an arc extending through southeastern New Hampshire to southern Maine. Isolated eastern populations occur in southern Nova Scotia and in the lower Hudson Valley of New York.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Blanding's turtles are semi-terrestrial during the spring and summer active seasons and use a variety of aquatic and terrestrial habitats. They readily make long overland movements between aquatic habitats. In Massachusetts, Blanding’s turtles are found in ponds with mucky or organic substrates, abundant submerged and emergent vegetation, and basking objects (usually fallen logs or vegetation). New England Blanding’s turtles frequently reside in kettle holes (depressions associated with glacial outwash), vernal pools (ephemeral or seasonal ponds), deep marshes, shrub swamps, lake and pond margins, and the floodplains of medium-sized, slow-flowing rivers. Common vascular plant species found in Blanding's turtle habitats include buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), sedges (Carex spp.), bulrushes (Scirpus spp.), and cattails (Typha spp.). Blanding's turtles need suitable upland habitats to nest. These habitats usually have well-drained, sandy or gravelly soils and good solar exposure, as are found commonly along powerline and gas line corridors, playing fields, roadsides, rail beds, gravel pits, lawns, and gardens. By late October, Blanding’s turtles return to their overwintering locations in ponds, marshes, shrub swamps, and deep vernal pools, where they select sites with organic substrate or root structure. While they often use the same general overwintering site several years in a row, they also will switch ponds or wetlands entirely if one becomes unsuitable—however, this can result in new road-crossing activity. Some individuals overwinter under hummocks in buttonbush, red maple, or highbush blueberry swamps.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Adult female Blanding’s turtle, showing the characteristic yellow throat, streaked upper jaw, and faint spotted markings on the carapace.

Like several other species in the emydine (subfamily Emydinae) clade of turtles, Blanding's turtles have an overall life history that leaves them vulnerable to habitat fragmentation and human activity, including (a) a tendency to travel long distances overland during the active season, increasing their exposure automobiles; (b) delayed maturity around 14–18 years old, resulting in slow population growth and recovery from declines; (c) low nest and juvenile survivorship, making it difficult for populations to recover from population collapse; and (d) low rates of dispersal and an inability to colonize new habitats quickly.

Roads are a primary threat to Blanding's turtle population persistence in Massachusetts. Blanding’s turtles frequently travel between multiple wetlands in any given year. Female Blanding’s turtles often cross roads when searching for optimal nesting sites. Roads increase mortality risk and also contribute to habitat fragmentation. Habitat loss and degradation are also major threats. Commercial and residential development continues to fragment and degrade important habitats. Other threats include the depredation of nests and juveniles by subsidized small- to mid-sized carnivores (e.g., chipmunks, raccoons, skunks) and collection for pet markets. These and other threats are compounded by climate change: increasing summer temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns will likely affect hydroperiod and water levels, in turn influencing foraging and overwintering habitat selection. These threats are best mitigated by a landscape-level conservation strategy that protects large, unfragmented blocks of habitat where dynamic wetland processes result in abundant and diverse aquatic habitats.

Conservation

Adult male Blanding’s turtle, showing the characteristic yellow throat, dark upper jaw, and reticulated markings on the carapace margin.

Conservation planning

For more than 20 years (since 2004), the northeastern states with Blanding’s turtle populations (MA, NH, ME, NY, PA) have convened as a “Northeast Blanding's Turtle Working Group” in order to pursue shared objectives of viable and resilient Blanding’s turtle populations. In 2014, this working group developed a regional conservation plan to identify, conserve, and manage Blanding's turtle populations in the Northeast, which was updated in 2022. The plan is based on extensive field-based population assessments, a standardized population assessment program, landscape and species distribution modeling, and microsatellite-based genetic analyses. The working group delineated a “conservation area network” of top-priority sites to prioritize conservation and management efforts regionally. Priority sites were selected based on factors such as population size, habitat quality, landscape context, habitat quality, and regional representation. A total of 36 sites across the region were designated as high priority, including nine sites in Massachusetts. Two of Massachusetts’ priority sites were first studied in the 1970s (by Terry Graham and colleagues) and 1980s (by Brian Butler and colleagues). Standardized sampling of this broad site network occurred in 2012–2013 and repeat sampling in 2017–2019 allowed for an evaluation of population trends and habitat change. Population estimates showed relative stability over this short window within mostly protected sites, although there was variation between sites. The plan recommends continued conservation efforts, including habitat protection and population monitoring, to ensure the long-term survival of Blanding's turtles in the Northeast.

Inventory and monitoring

Additionalinventory of potential Blanding's turtle habitat is needed to identify and prioritize areas for conservation. Naturalists in Massachusetts can help to document the distribution of this species in Massachusetts by photographing basking turtles (with a long lens or spotting scope from a distance) and reporting areas where Blanding’s turtles are killed on roadways (with photographic documentation). This information should be reported through the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program’s Heritage Hub. The following areas in Massachusetts are data-deficient: (1) eastern Essex County, especially east of I-95, (2) most of Bristol County, and (3) northern and western Worcester County. There are reliable (but unverified) sight records in Massachusetts as far west as Athol, aligning roughly with the westernmost distribution in adjacent New Hampshire. There are a few other, scattered records on the Worcester Plateau north of Mount Wachusett, but the size and viability of these populations are not known.

The regional standardized monitoring program with New Hampshire, Maine, Pennsylvania, and New York should continue at roughly 10-year intervals to track population trends, habitat use, and changes in the landscape, and to discover new populations. Monitoring should include both field surveys, hoop trapping, and remote sensing technology. Environmental DNA (eDNA) and drones could prove a useful and noninvasive method of demonstrating recent use of specific wetlands. Any trapping or handling of turtles will require a permit from MassWildlife.

Research needs

Scientific research should investigate the factors influencing Blanding's Turtle population dynamics and habitat use, as well as the effects of changing precipitation patterns and warming temperatures. Specific research needs include: (a) assessments of genetic diversity and connectivity between populations, and studies of relatedness to evaluate dispersal patterns and population structure; (b) studies of density-dependent population dynamics to understand how populations respond to changes in habitat and resource availability, including beaver-influenced vegetation dynamics and hydrological regimes; (c) road ecology studies to prioritize roadkill “hotspots” for mitigation and to develop effective road mitigation measures and reduce turtle roadkill; and (d) studies of the effects of habitat management on population viability.

Management

Blanding's turtle populations in Massachusetts are evaluated and managed at both the site and watershed level. There are numerous publicly-owned properties that support important Blanding’s turtle populations. For example, MassWildlife’s Northeast, Southeast, and Central Districts oversee Wildlife Management Areas that are within priority Blanding’s turtle sites and their management and conservation work are essential to the continued persistence of the species in the Commonwealth. MassWildlife should also continue to work collaboratively with the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Eastern Massachusetts National Wildlife Refuge, and key municipalities (especially in Essex and Middlesex Counties) to protect and manage key habitats. Key partners—including Zoo New England, Parker River Clean Water Association, and Bristol County Agricultural High School—will ideally continue their dedicated site-level conservation programs. The ongoing management of high-priority sites should focus on maintaining and enhancing habitat quality and promoting connectivity between areas of suitable and likely habitat. Key actions will include wetland restoration, creation of nesting habitat, and removal/control of invasive plants. Key municipalities should also incorporate Blanding's Turtle conservation into their planning efforts. Road mortality mitigation is critical, including the strategic installation of wildlife crossing structures, exclusion fencing along roads, and reduced speed limits in key areas (based on the actual configuration of the site). There are strong, ongoing partnerships with MassDOT in the planning and regulatory stages to address road mortality. Public education and outreach are essential to promote responsible land management practices. Educational materials should be developed for private landowners, and workshops should be held to inform the public about Blanding's Turtle conservation efforts.

References

Baker, R.E., and J.C. Gillingham. 1983. An analysis of courtship behavior in Blanding’s Turtle, Emydoidea blandingi. Herpetologica 39:166–173.

Congdon, J.D., A.E. Dunham, and R.C. van Loben Sels. 1993. Delayed sexual maturity and demographics of Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii)—Implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. Conservation Biology 7, 826–833.

Congdon, J.D., and R.C. van Loben Sel,. 1993. Relationships of reproductive traits and body-size with attainment of sexual maturity and age in Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii). Journal of Evolutionary Biology 6, 547–557.

Ewert, M.A., and C.E. Nelson. 1991. Sex determination in turtles: Diverse patterns and some possible adaptive values. Copeia 1991:50–69.

Ernst, C.H., J.E. Lovich, and R.W. Barbour. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London.

Grgurovic, M., and P.R. Sievert. 2005. Movement patterns of Blanding’s Turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) in the suburban landscape of eastern Massachusetts. Urban Ecosystems 8:201-211.

Jones, M.T., and P.R. Sievert. 2012. Elevated mortality of hatchling Blanding's turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) in residential landscapes. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 7:89–94.

Joyal, L.A., M. McCollough, and J.M.L. Hunter. 2000. Population structure and reproductive ecology of Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) in Maine, near the Northeastern edge of its range. Chelonian Conservation and Biology3:580–588.

Sievert, P.R., B.W. Compton, and M. Grgurovic. 2003. Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) conservation plan for Massachusetts. Report for Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. Westborough, MA.

Willey, L.L., M.T. Jones., M. Parren, E. Nichols, and the Northeast Blanding’s Turtle Working Group. 2021. Revised Conservation Plan for the Blanding’s Turtle and Associated Species of Conservation Need in the Northeastern United States. Technical Report to New Hampshire Fish and Game Department and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Contact

| Date published: | March 14, 2025 |

|---|