Bird Harassment Program

The Bird Harassment Program operates to limit pollutants from primarily gulls, ducks and geese. Harassment involves several actions including the use of scare-techniques, such as noisemakers, to push the birds from shore and then using boats to keep them moving. With enough harassment, the birds relocate to other areas of the reservoirs further from the intakes.

The Bird Harassment Program on the Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs is ongoing, operating two to three times per week in the evenings from October to April when conditions allow (e.g., no ice cover or inclement weather). Because of the overall reduction in gull numbers that roost on the reservoirs, which is partially attributed to the work conducted from our studies, the Bird Harassment Program has been scaled back over the years.

Find out more about the Bird Harassment Program in the Wachusett Reservoir Bird Harassment Program History: 1990-2023.

-

Open PDF file, 8.1 MB, Wachusett Reservoir Bird Harassment Program History: 1990-2023 (English, PDF 8.1 MB)

DCR DWSP Gull Study

As part of the Bird Harassment Program and to fill gaps in knowledge, DCR conducted a study on the movements and behaviors of the three most common species of gulls that roost nightly from September to April on Wachusett and Quabbin Reservoirs. These species are the Ring-billed (Larus delawarensis), Herring (L. smithsonianus), and Great Black-backed (L. marinus) Gulls. This study ran from 2008 to 2017.

Goals of this decade long effort included:

- Studying regional movements of gulls

- Understanding feeding behavior and roosting patterns

- Using new knowledge to determine feasible mitigation measures for reducing high numbers of gulls at the reservoirs.

Capture and Tagging

Development of the study spanned January to March of 2008, using the following three safe-capture techniques:

- A walk-in nest trap

- Steele’s net

- A net launcher

The net launcher proved to be the most effective, and by the fall of 2008, it was used exclusively to capture gulls for the remainder of the study.

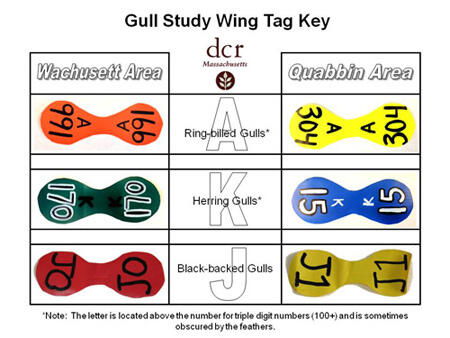

Following capture, all birds were fitted with a uniquely numbered aluminum federal band on one leg and a uniquely numbered colored band on the opposite leg. Birds were also fitted with color-coded, alpha numeric vinyl wing-tags attached to each wing from 2008 to 2013. Neither the wing-tags or leg bands impact the bird’s movement and made individual identification possible from a distance. Wing-tag color-coding was based on the species of bird captured and capture site’s proximity to either Wachusett or Quabbin Reservoir.In addition to banding and tagging, all gulls were sexed, aged, weighed and measured before being released unharmed.

All capture and banding efforts were conducted by trained biologists under a federal U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Bird Banding Laboratory (BBL) permit and a Massachusetts-issued scientific permit.

Tag Examples

Plastic Colored Leg Bands

Federal Aluminum Leg Band and Number Colored Leg Band

Unique number Wing-tags

Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoir Wing-tag Codes

Tracking and Data Collection

Via Satellite

Several gulls were fitted with satellite transmitters instead of wing-tags. Four types of transmitters were utilized:

- A 45-gram GPS equipped transmitter on the larger, adult great black-back gull

- 30-gram and 22-gram GPS equipped transmitters on adult herring gulls

- A 20-gram non-GPS equipped satellite transmitters on herring gulls

- A 9.5-gram non-GPS equipped satellite transmitter for the ring-billed gulls

All transmitters were lightweight and solar-powered, with the potential to last several years. In all, transmitters were attached to 21 ring-billed gulls, 14 herring gulls, and one black-backed gull. Data collected from each transmitter revealed detailed information about the movement patterns, feeding locations, and roosting sites for these gulls, which provided insight about the behavior of the general gull population.

Visual Observation

Wing-tagged gull sightings were reported with the location, tag color and number, by field biologists, students, citizen birders and the general public throughout the east coast region and maritime Canada as the birds moved about freely. Most sightings came directly to DWSP through email or phone calls, but some were reported directly to the Bird Banding Lab, which operates in partnership with the Canadian Wildlife Service.

Gull Study Findings

Completion of the research study in 2017 provided very interesting and relevant information about the life history of gulls wintering in Massachusetts and spending time at the Reservoirs.

- Food sources for gulls were overwhelmingly found to be of human origin.

Gulls roost on the Reservoir overnight, but by day they forage for food at large shopping centers and restaurant parking lots, feeding on handouts from well-meaning but misinformed individuals. In addition, waste water treatment facilities, various agricultural sites, and landfills provide a reliable and significant source of food for gulls in central Massachusetts. Abundant human-derived food sources leads to an abnormally high population of gulls in the region. - Gull movement patterns between feeding, loafing (resting) and roosting sites were found to be very consistent.

Most gulls visited the same locations year after year. Known as “site fidelity,” this knowledge is useful for developing a gull management program. Because the same gulls return to the reservoirs and same feeding locations year after year, that same population of gulls can be effectively discouraged from their habitual behavior, reducing the total number of gulls in the area. - All gulls in the study spent time at Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs at some point in time.

Gulls roosted on DCR water supply reservoirs and “alternate roosts” such as smaller lakes and ponds in central Massachusetts, but all gulls in the study spent time at Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs at some point. Whether a gull chose to roost on a DCR reservoir or another location was often decided by how close that water body was to their feeding site or the amount of ice cover on the smaller water body. - Nesting and migration habits of the Massachusetts gull population showed they went far and wide before returning to central Massachusetts.

It was determined that most of the ring-billed gulls in this study bred further north at Lake Champlain or the Great Lakes of eastern Canada. It was also found that as winter progressed the gulls tended to travel further south in search of more hospitable conditions.

Details on the findings of the gull study can be found in the Research Articles section below.

Actions Taken As a Result of the Gull Study

As a result of the Gull Study, DWSP initiated a "Do Not Feed The Gulls" publicity campaign and worked with local towns, facilities and businesses to mitigate human-derived food sources for gulls.

- Informational signage was placed at key hand-feeding locations throughout central MA explaining the negative impacts of feeding gulls.

- Local Towns responded to our informational campaign by passing local ordinances to make feeding gulls illegal.

- Brochures, educational presentations, and similar outreach efforts were developed to get the word out discouraging people from feeding gulls in order to protect water quality.

Other sources of food were also identified, and steps were taken to eliminate the availability of this food, including:

- Installation of wires over wastewater treatment plant tanks to reduce gull activity at these facilities. DWSP worked with waste water treatment plants in central Massachusetts to install wires. While the wires do not physically exclude the gulls, they create a visual barrier that gulls tend to avoid, likely due to a psychological aversion toward unfamiliar or potentially hazardous obstacles.

- DWSP collaborated with USDA at local landfills to ensure the bird harassment was taking place at these facilities to limit feeding opportunities.

- DWSP worked with local farmers to mitigate gull feeding activity by constructing protected feeding areas for the livestock.

The above measures significantly reduced feeding opportunities and reduced the overall number of gulls found roosting on the Reservoirs. Study findings also provided useful guidance that helped direct ongoing gull monitoring activities.

DWSP continues to monitor gulls in the region, updates signage and mitigation measures as needed, and conducts the Bird Harassment Program on the Reservoirs. Trapping, banding and tracking of movements is currently not being conducted, but these activities may resume if needed.

-

Open PDF file, 264.7 KB, DCR Watershed Do Not Feed the Gulls Brochure (English, PDF 264.7 KB)

How the Public Can Help the Gull Study

Report wing-tags or band numbers! The last wing-tagged gull was reported in February 2020. As wing-tags wear-out and fall off over time it is highly unlikely that any wing-tags remain on the study gulls. But if a gull with a wing-tag or leg-band is seen, the alpha-numeric combination on the tag (e.g., A57) should be reported using the contact information below or to the federal Bird Banding Laboratory. Gulls fitted with leg bands may still be seen, but bands are much harder to read. If any leg band information is collected, those data would be helpful to our program.

If you have gull leg band or wing-tag information, please contact Elise Stanmyer.

Why Feeding Gulls Is Discouraged

Some well-meaning individuals mistakenly believe that hand-feeding gulls bread, crackers or other human food is helpful. In the interest of drinking water quality as well as the overall health of the gulls themselves, there are several reasons NOT to feed the gulls;

- Large numbers of gulls visiting the Reservoirs causes an increase in the level of fecal coliform in the water, compromising water quality. Providing food to wintering gulls encourages them to stay in central MA and use these reservoirs for roosting.

- As scavengers, gulls will heartily feed on almost anything they perceive as food. Bread, crackers or other human food lacks the nutrition found in a more naturally foraged diet. While the bird may fill up, short and long term health implications can result, making the bird less healthy, and potentially impact reproductive success.

- Throwing food to aggressively feeding gulls creates a close-contact situation for the birds and humans where disease and pathogens are more easily spread between the birds and from the birds to people.

- Feeding gulls also creates aggressive behavioral issues. Once gulls recognize humans as an easy source of food, anglers, beach-goers, campers and picnickers are in danger of being swarmed by attacking gulls in search of food.

Because of the reasons listed above, "No Feeding" ordinances have been enacted in certain municipalities including Worcester (Chapter 8, Section 9B) and Leominster (Chapter 14, Section 14-19), where feeding gulls is illegal and punishable by fine.

-

Open PDF file, 264.7 KB, DCR Watershed Do Not Feed the Gulls Brochure (English, PDF 264.7 KB)

Other Ongoing Gull Monitoring and Management Efforts

Regional Surveys

DWSP surveys the region from October through March to monitor for gull activity at regular problem feeding areas, as well as searching for new food sources that could be attracting gulls. Regular visits are made to parking lots with fast food restaurants and shopping plazas, wastewater treatment facilities, landfills, livestock farms, and local waterbodies, to count and identify species of gulls. Posts on eBird and reports to Massachusetts birding groups are periodically reviewed for new information on gull activity. New signage is installed in cooperation with landowners, and brochures are handed out to those feeding gulls to provide education on why feeding gulls human food items is unsafe.

Roost Surveys and Drone Roost Study

Roost surveys are conducted weekly from September to April on Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs. The survey takes place from a location that allows for convenient viewing of the roosting gulls, aided by binoculars and spotting scopes. Gulls are identified by species, if conditions permit, and a count is taken. Numbers are reviewed to determine how they correlate with observations made on regional surveys and with bacteria numbers on the Reservoirs.

DCR has developed a partnership with the MassDOT Aeronautics division to enhance traditional roost survey methods (binocular and spotting scope) and to count gulls in difficult to reach areas. Starting in 2020, the partnership has used Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS or “drones”) to study the roosting behavior of gulls at Quabbin Reservoir. Roosts distant from the shore or in remote locations can be difficult to accurately count and, in some cases, even find. Drone use has made this task much easier to accomplish.

Each week starting in early October until the following spring, DCR and MassDOT staff fly a drone mission over the Quabbin Reservoir in search of roosting gulls. When a roost is identified, high quality images and video are made. Viewing the information on office computers, DCR staff can count the individual number of gulls in the roost and sometimes even distinguish between gulls species. This information is used to track the size, location, and species mix of the roost. Knowledge of roost size and location on the reservoir informs DCR’s Bird Harassment Program. If numbers increase, DCR can respond accordingly and step up harassment efforts as needed.

The MassDOT drone program is also utilized a couple times a month at Wachusett Reservoir. Though the roost is easier to locate at Wachusett, counting can be more challenging as roost numbers are typically higher at Wachusett than at Quabbin. Photos or videos from above the roost allows for a more accurate count.

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) and Gulls on Water Supply Lands

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) is a highly contagious disease affecting wild and domestic birds. It has been confirmed in deceased birds across the Northeast, including Massachusetts. Birds most at risk include waterfowl, raptors, and scavengers, though any species can be susceptible.

As of early 2025, there have been no observed impacts of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) on the gull populations using water supply reservoirs.

While some gull mortality (possibly due to HPAI) has been documented along the Massachusetts coast this year, no inland cases have been reported. Gulls are particularly susceptible to HPAI due to their social behavior—congregating in large groups and often interacting with other infected birds. Additionally, their scavenging habits increase the risk of contracting the virus from diseased carcasses. Past research conducted by researchers at Tuft’s Runstadler Lab (formerly at MIT) in concert with DWSP's prior trapping efforts, indicated that some individual gulls carried avian influenza virus.

Research Insights on HPAI in Gulls

Recent studies highlight that gulls play a role in the spread of avian influenza, particularly during migration.

- Young gulls that have hatched on the highly concentrated gull breeding grounds tend to have the highest infection rates in gulls.

- Fall is the peak season for the virus because gulls from different places come together, making it easier for the virus to spread as gulls begin their long-distance migration by the end of breeding season (April- September).

- As gulls grow older, they seem to build up immunity.

- Even though gulls may develop immunity, their immune system may weaken during migration, making them more vulnerable to reinfection.

- Gulls in urban areas of the Massachusetts coast show higher chance of having the virus than those inland (near the Wachusett and Quabbin Reservoirs), likely due to greater interaction with more waterbird species.

Why Does This Matter?

Gulls move between cities, coasts, and reservoirs, which means they could spread the virus to other birds and even humans. Understanding when and how they get infected can help scientists predict and prevent outbreaks of avian flu (HPAI).

Ongoing Efforts

While the potential for HPAI contamination in open drinking water sources exists due to shedding by infected birds, standard water treatment processes, including the chlorination process used by the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority (MWRA), are effective in inactivating the virus. Consequently, the risk of HPAI transmission to humans through properly treated drinking water is considered low.

However, recently birds such as Canada geese, have tested positive in areas near DWSP reservoirs and watershed water bodies. As a result, DWSP remains committed to monitoring and mitigating the risks of HPAI to protect both long-term water quality and wildlife.

Important Avian Influenza Guidelines

- Do not feed wildlife – congregating birds increases disease spread.

- Avoid handling sick or dead birds – though rare, human infection is possible.

- Do not bring sick or dead birds to a rehabber, vet, or clinic without prior approval to prevent further spread.

Reporting Sick or Dead Birds

- Contact local Animal Control or a wildlife clinic.

- For clusters of five or more sick or dead birds, use the Mass Fish and Wildlife Report Bird website.

Research Articles

The results of DCR's Division of Water Supply Protection's gull study have been documented in several research articles.

- Ecological Divergence of Wild Birds Drives Avian Influenza Spillover and Global Spread (2022)

- Age and Season Predict Influenza A Virus Dynamics in Urban Gulls (2021)

- Both Short and Long Distance Migrants Use Energy-minimizing Migration Strategies in North American Herring Gulls (2020)

- Winter Home Range and Habitat Selection Differs Among Breeding Populations of Herring Gulls in Eastern North America (2019)

- Fidelity and Persistence of Ring-Billed and Herring Gulls to Wintering Sites (2016)

- Roost Site Selection by Ring-Billed and Herring Gulls (2016)

- Assessing Gull Abundance and Food Availability in Urban Parking Lots (2015)

- Evaluation of a Net Launcher for Capturing Urban Gulls (2014)

- Stainless-steel Wires Exclude Gulls from a Wastewater Treatment Plant (2013) Abstract Only

- The Life and Travels of Ring-billed Gulls (2011) Excerpt from MassWildlife Magazine

Contact

Address

| Last updated: | May 14, 2025 |

|---|