- Trial Court Law Libraries

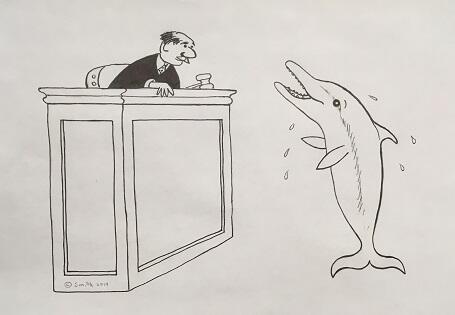

A dolphin walked up to the bar in Massachusetts, but was told it had no standing.

Well, at least legally.

A male dolphin named Kama was named as a plaintiff in a case in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts in 1993. Citizens to End Animal Suffering & Exploitation, Kama, et al. v. New England Aquarium, 836 F. Supp. 45 (United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, 1993)

Kama, joined by animal rights groups, was suing on the basis of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), because Kama had been sent (without his consent) from an aquarium to the Department of the Navy (to take up military duties). The MMPA requires a permit for anyone to “take” a marine mammal, and allows injured parties to sue for its enforcement.

The court ruled that Kama lacked standing to sue, because Congress did not expressly say that animals could have standing under that particular law, but implied that Congress could give animals standing if Congress so wanted.

“If Congress and the President intended to take the extraordinary step of authorizing animals as well as people and legal entities to sue, they could, and should, have said so plainly…This conclusion is reinforced by consideration of F.R.Civ.P. 17(b), which falls within the section of the Rules entitled ‘Parties’ and discusses the ‘capacity of an individual to sue or be sued’…While this provision generally addresses the capacity of corporations, partnerships, and other business entities to litigate, there is no indication that it does not apply to other non-human entities or forms of life… [T]he MMPA and operation of the F.R.Civ.P. 17(b) indicate that Kama the dolphin lacks standing as a matter of law.” (p. 49)

To understand this, one must understand the three basic requirements for standing: Article III standing, prudential standing, and statutory standing.

Article III, section 2, cl. 1 of the U.S. Constitution sets out three requirements for standing: (a) Injury-in fact; (b) causation (the injury must have been caused by the defendant), and: (c) redressability (a favorable decision by the court would be able to redress the injury).

In addition to Article III standing, one must have “prudential standing”, which is established by the court rules. These state, in essence, that the party suing must be either the injured party, or an acceptable surrogate, as defined by the rules. In Massachusetts, this would be Massachusetts Rule of Civil Procedure 17 (itself a rewording of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 17).

Furthermore, one must have “statutory standing”, meaning that a plaintiff must have an injury falling within the “zone of interests” that the statute was meant to protect. Some statutes specifically provide for citizen suits. (Other laws are enforced only by the government; some allow for both government enforcement and civil suits.) For example, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) provides for citizen suits against violators of that law, or against the government to cause it to enforce the law, if the citizen is personally injured by the violation, and it specifies what “person” means under that law. If a specific statute doesn’t provide for citizen suits, a plaintiff may sue under the APA (Administrative Procedure Act) (5 USC s.551-559); if so, the court must determine whether the plaintiff is within the “zone of interests” of that law. The court has interpreted the APA (Administrative Procedure Act) to mean that affected “persons” have standing to sue under the MMPA. But the APA does not define “person” to include animals.

Therefore, the court acknowledged that Kama may have been entitled to Article III standing (because his “injury” was real, was caused by an action by the aquarium and the Navy, and could be redressed by his return to the aquarium), but under the particular statute (MMPA) that formed the basis for his complaint, he was not a “person”, so he did not have standing.

This was not the only time a dolphin was left high and dry by the court: In an earlier case in Hawaii, a dolphin also didn’t have standing as a “person” to sue for its freedom, after two dolphins were ‘liberated’ from their enclosures by a lab assistant. State of Hawaii v. LeVasseur, 613 P. 2d 1328 (Int. Ct. App., Hawaii, 1980). The lab assistant was sentenced to 6 months in jail with 5 years of probation (for theft).

However, the American Cetacean Society (whale watchers) was ruled to have standing to sue to try to protect whales from hunting, since the express purpose of their organization was to watch and study whales. Japan Whaling Assn. v. American Cetacean Soc., 478 U.S. 221 (1986). The difference is that it was humans suing for their ability to see whales (thus only indirectly, albeit intentionally, benefitting whales), not whales suing on their own behalf. (The A.C.S. lost this case on other grounds.)

Probably the most complete analysis of the issue of standing, as it regards animals, is to be found in the case Cetacean Community v. Bush, 386 F 3d 1169, 1175 (U.S. Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit, 2004). The plaintiffs (the sole plaintiff) were “all the world’s whales, dolphins, and porpoises…, through their self-appointed lawyer”. They challenged the U.S. Navy’s use of sonar, as it hurts the animals physically and interferes with their behavior (eating, mating). The cetaceans sued pursuant to the Endangered Species Act, MMPA, APA (Administrative Procedure Act), and NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act). The Court ruled (agreeing with the Kama case) that the animals lacked statutory standing, but that Article III would have allowed Congress to grant animals statutory standing. (1175-76, 1179).

“[W]e see no reason why Article III prevents Congress from authorizing a suit in the name of an animal, any more than it prevents suits brought in the name of artificial persons such as corporations, partnerships or trusts, and even more ships, or of juridicially incompetent persons such as infants, juveniles, and mental incompetents.” p.1176

Lastly, we would like to provide a brief update on the case of Naruto, a macaque monkey who sued for copyright of photographs he took of himself, and which were later published in a book. (See our previous blog, Can a Monkey Own a Copyright?) In a recent appeal, Naruto, a Crested Macaque v. Slater, 2018 (U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit), 888 F.3d 418 (April 23, 2018), the court held that: (1) the organization [PETA] that was suing on Naruto’s behalf lacked standing to sue as the monkey’s next friend; (2) the complaint alleged facts sufficient to establish Article III standing for the monkey; and (3) the monkey, because it was a non-human, lacked statutory standing under the Copyright Act. The court chafed at having to admit that a monkey could have Article III standing, but said that it had no choice but to admit the precedent of Cetacean Community v. Bush.

Written by Gary Smith