- Scientific name: Lachnanthes caroliniana (Lam.) Dandy

- Synonymy: Lachnanthes caroliana

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Redroot, also known as Carolina redroot, Lachnanthes caroliana, is a slender, erect perennial herb in the bloodwort family (Haemodoraceae). Its leaves resemble those of irises—flattened in one dimension—but are paler green and more slender, growing in several clumps. From the center of each clump arises a stem 30-80 cm (11.5-30 in) tall, smooth below and becoming woolly near the inflorescence. The three-petaled flowers are yellowish and occur in dense clusters that may be flat-topped or rounded. The entire inflorescence is densely woolly and yellowish white, measuring 3-8 cm (1.2-3 in) wide.

Life cycle and behavior

This is a perennial species. Flowering occurs from early July through late August.

Population status

Redroot is listed a species of special concern under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. Since 1999, 18 occurrences have been verified in Barnstable and Plymouth Counties. An additional 16 occurrences have not been relocated and are now historical.

Distribution and abundance

Redroot occurs in disjunct coastal plain populations in Nova Scotia, southeastern Massachusetts, Long Island, southern New Jersey, and from Maryland south to Florida, Louisiana, and Cuba. In New England, It is not known from Maine, New Hampshire or Vermont. It is considered critically imperiled in Connecticut and Rhode Island, and vulnerable in Massachusetts.

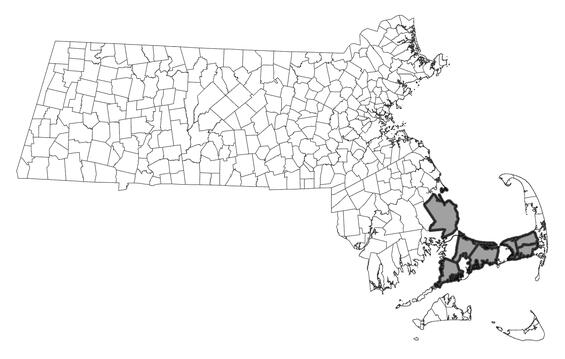

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Redroot inhabits exposed sandy to peaty shores of coastal plain ponds. It typically grows in linear bands along the middle to upper margins of the shore or in sheltered coves. These habitats rely on pronounced seasonal fluctuations in water levels, typical of kettlehole ponds that lack inlets or outlets. Water levels generally rise in the winter and spring and fall during the summer and autumn, driven by rainfall and groundwater movement.

Common pondshore associates include Plymouth gentian (Sabatia kennedyana), threadleaf sundew (Drosera filiformis), and golden hedge-hyssop (Gratiola aurea).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

As with all coastal plain pondshore species, its persistence is tied to the natural hydrology of its habitat. Redroot and other pondshore species face significant threats from habitat loss due to housing and recreational development around ponds. Additional threats include declining water quality from runoff and leaking septic systems, as well as changes to the natural water table. Abundance varies year to year depending on water levels. The species may survive in a dormant state for multiple years under unfavorable conditions.

Conservation

Surveys for redroot are needed on a regular basis, preferably every 10 to 15 years. It is recognizable in vegetative form but is most easily observed when in bloom or fruit in July into the early fall.

Management needs for redroot include protection of the shorelines where it grows, particularly isolated coves. This will prevent accidental trampling by recreational users. Ensuring that water quality in the coastal plain ponds where redroot occurs is important. In addition, it is likely that invasive species such as common reed (Phragmites australis) and gray willow (Salix cinerea) will need to be controlled to prevent negative impacts on the species if they are observed in the same ponds. All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

The exact ecological needs of this species are not known. Research is needed to determine how long the seed in the soil will last, and whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, this strategy could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

Holmgren, N.H. 1998. The Illustrated Companion to Gleason and Cronquist’s Manual. The New York Botanical Garden.

Contact

| Date published: | April 30, 2025 |

|---|