Hundreds of sites along the 1,500 miles of Massachusetts shoreline are owned by government agencies or major nonprofits and are open to the public. From expansive beaches to sweeping scenic vistas to public harbor walks, it is easy to understand why these beautiful coastal sites have been preserved and protected for their natural resources and recreational opportunities. What may not be as apparent is the history of these sites and their former incarnations as amusement parks, military installations, quarrying operations, and more. The fascinating and sometimes convoluted history of seven coastal public access sites in the Bay State are summarized below, along with information on how and why they came to be protected and how to get there so you can enjoy them yourself.

Cape Cod National Seashore, Outer Cape Cod

Long before the Cape Cod National Seashore was even considered for federal protection, this stretch of shoreline was recognized for its abundant natural resources and beauty. As early as the 1600s, records indicate that Plymouth Colony put aside parts of the area as a fisheries reserve and pastured cows in the dunes. In the 1800s, famed author and philosopher Henry David Thoreau recognized and documented the magnificence and vastness of the Great Outer Beach. In 1939, talks began to create a national park extending from the tip of Cape Cod all the way to Duxbury Beach—which was ultimately scaled back to include only the outer portion of Cape Cod. Though smaller in scope, a delicate balance had to be found between the interests of the many landowners (since much of the land was privately owned) and the preservation of the scenic, natural, and historic features of the area. Fortunately, a multi-year process yielded success, and in 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed legislation establishing the Cape Cod National Seashore—a federally protected 40-mile (43,000-acre) stretch of land running from Provincetown to Eastham. The seashore includes the largest uninterrupted stretch of beach on the East Coast, and contains the Province Lands area in Provincetown—the second-oldest “common lands” in the nation (the first being Boston Common). In addition to the beaches and dunes, numerous salt marshes, fresh- and salt-water ponds, forests, and lighthouses are accessible by many hiking and biking trails. See the National Park Service’s (NPS) Cape Cod National Seashore web page for more information about the park’s natural resources, history, and culture, or to plan a visit. See the NPS History & Culture page for more about the people (such as Guglielmo Marconi), places (such as the Three Sisters Lighthouses and Old Harbor U.S. Life Saving Station), stories (such as about shipwrecks), and archeology of the outer Cape. For information on the historic legislative bill that established the seashore, see MassMoments.

Halibut Point State Park, Rockport

The area now known as Halibut Point State Park (named by sailors who needed to “haul about,” or tack, to get around this portion of Cape Ann) was first used by groups of Pawtucket Indians, who came to the coast on a seasonal basis to hunt and gather the abundant resources found here. European settlers that arrived in the 1600s farmed the area and grazed cattle on the coastline. In 1755, Cape Ann was the site of one of the largest earthquakes known to have taken place in New England, and research has since proven that this area is the third most geologically active area in the United States. Beginning in the 1840s, Halibut Point—with its abundance of granite with a uniquely high density due to the weight of glaciers from ice ages past—was the site of a thriving quarry industry (evidence of the quarrying can still be seen today; the main quarry is now filled with water and is the Babson Farm Quarry Pond). In 1929, upon the collapse of the quarry industry, The Trustees of Reservations was able to acquire 17 acres of the area to be preserved as the Halibut Point Reservation. The remainder of the property was used for various activities for the next 50 years—including for university research, a private park, and a failed large-scale development—and a 60-foot fire control tower on the site helped guard Boston and Portsmouth Harbors during World War II. In 1981, the state acquired 56 acres to create Halibut Point State Park. The reservation and park are now cooperatively managed by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and The Trustees of Reservations. An adjacent property, Sea Rocks, is owned by the town of Rockport and is also open for public use. Visitors can visit the old quarry pond, trails, tidepools, and rocky ledges, including the tip of the Overlook at Halibut Point—the closest spot to Europe in the continental United States, and a great place to check out the view. For information on how to get there and a map of the park, see DCR’s Halibut Point State Park web page. For additional information about the park’s natural resources, history, and visitors center (located in what was the former fire control tower), see DCR’s Halibut Point State Park brochure (PDF, 725 KB).

Horseneck Beach State Reservation, Westport

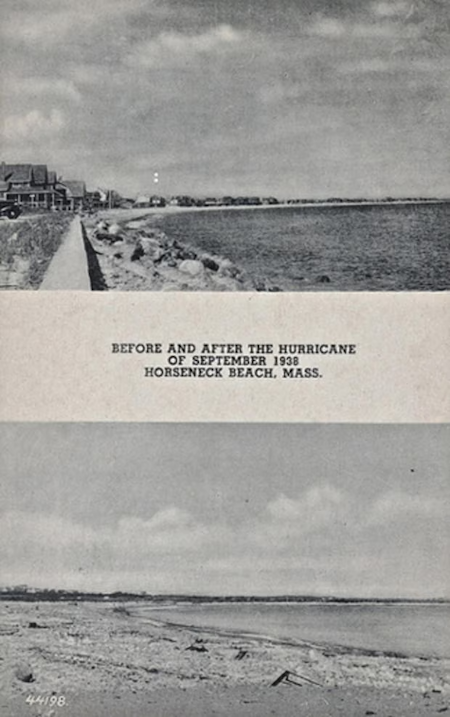

Horseneck Beach State Reservation is located within the town of Westport—once known as the lands of Old Dartmouth, which were purchased in 1652 by the Plymouth Colony from a Wampanoag chief (in exchange for “thirty yards of cloth, eight moose-skins, fifteen axes, fifteen hoes, fifteen pairs of breeches, eight blankets, two kettles, one clock, two pounds in wampum, eight pair stockings, eight pair shoes, one iron pot, and ten shillings”). Settlers came to the area to escape religious persecution by the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies and to search for greater opportunities provided by the fertile agricultural land, coastal resources, and protected harbors. Within Westport, the early settlers clustered their homes in the area of Horseneck Beach and Westport Point, on an oddly shaped peninsula where they could more easily defend themselves against Native tribes. Much later in 1887 and 1888, a jetty and the Westport Lifesaving Station were built at the harbor entrance along the west end of Horseneck Beach to aid navigation and to prevent shipwrecks. In the early 1900s, Westport’s shoreline was steadily developed with summer homes, hotels, groceries, and even a bowling alley, and by 1924, a stone causeway was constructed from the beach to Gooseberry Island, allowing for numerous summer homes to be built. However, a devastating storm—the 1938 Hurricane—wiped out most of the structures along the beach and island and completely altered the landscape. (Most of what was left was subsequently hit by Hurricane Carol in 1954.) Structures that survived these storms include the lifeboat station (though the station keeper drowned in the Hurricane of 1938) and parts of a military occupation that the U.S. Army built on Gooseberry Island as part of a coastal defense system during World War II. In 1950, Horseneck Beach State Reservation Area was established, permanently protecting this 2-mile stretch of sandy beach and 600 acres of barrier beach, salt marsh, and estuary habitats, as well as the now uninhabited Gooseberry Island. For more information on the fascinating history of this area, see Westport’s Historical Society’s Horseneck and Beaches web page or the Gooseberry Journal. For information on how to get to the reservation, see DCR’s Horseneck Beach State Reservation web page.

Nantasket Beach Reservation, Hull

Nantasket Beach, which derives its name from the Wampanoag word for “low tide place,” is located along the coast of Hull—a narrow peninsula town nearly surrounded by water. As early as 1621, Nantasket Beach was the location of a Plymouth Colony trading post (evidence can still be seen today in a clay-lined cellar alleged to be where Miles Standish traded with the Wampanoag tribe). As time passed in this seaside village, fishing and other seafaring trades became the way of life, and rescue and recovery of ships became the norm—circa 1786, one of the first Massachusetts Humane Society “huts of refuge” was located on the beach, and the rescue surfboat that was later launched from this area, the Nantasket, saved many lives. Over the next 100 years, the beautiful 5-mile stretch of sandy, ocean-facing beach evolved from an attraction for well-to-do families alone into a popular summer resort with grand hotels, clubs, and restaurants. The magnificent hotels, such as the Atlantic House built in 1895, were known to accommodate guests of wealth and fame, including presidents, duchesses, and actors. Steamer ships and a railroad (the Nantasket Beach branch being the first to operate by electricity through the third-rail system) made easy access available to this seaside destination. To entertain the crowds, Paragon Park was built with many amusement rides, including roller coasters and the well-known Paragon Carousel, an intricately carved, four-row, 66-horse carousel. While the carousel still exists today, the rest of Paragon Park closed in the mid-1980s. Nantasket Beach itself, however, still attracts many summer visitors for a day at the beach or a visit to seaside restaurants, shops, and public events, such as band concerts and the annual Waterfront Festival. For more information about the reservation, see DCR’s Nantasket Beach Reservation web page.

Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, Newburyport

In the late 1930s, the Massachusetts Audubon Society acquired 1,600 acres in the central part of Plum Island and converted it into a sanctuary, recognizing its importance for bird migration. In 1941, a much larger area was established as the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge—which according to Rachel Carson was “New England’s most important contribution to the national effort to save the waterfowl of North America.” The reason? The refuge was part of the great highway of bird migration—the Atlantic Flyway—and the only area in the northern part of the Flyway that could provide the important link in the chain of refuges along the East Coast. Located on the barrier beach island of Plum Island and extending over Plum Island Sound to Nelson Island, this refuge consists of 4,662 acres of sandy beaches and dunes, maritime forests, cranberry bogs, freshwater marshes, salt marshes, and numerous creeks and rivers, all of which support more than 300 species of birds (many of them migratory) and numerous other animals and plants. At the time of refuge establishment, preserving the economic uses of the land (such as for shellfishing, cranberry and beach plum harvesting, and salt haying) were a priority. Today, these uses are still protected and allowed with permits. Visitors can also access observation towers and foot trails through the dunes, thickets, and marshes to observe the barrier beach ecosystem and wildlife. For more on the environmental value of the refuge, see the 1947 brochure Parker River: A National Wildlife Refuge by Rachel Carson. To learn more about the refuge today and how to visit, see the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Parker River National Wildlife Refuge website.

Revere Beach Reservation, Revere

(Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Some people may pine for the days of the Point of Pines Hotel and Wonderland Park as the highlights of Revere Beach Reservation. Others may appreciate the long span of crescent-shaped beach and ocean vista that still exist today. One thing most people can agree on is that “America’s First Public Beach” and National Historic Landmark is a destination with a topsy-turvy history—from roller coaster rides to resorts to dog parks. The history of Revere Beach as a premier shoreline destination began in 1895 when the Massachusetts legislature entrusted the Metropolitan Park Commission with approximately 3 miles of coastal land to be managed for the best use by the public (taking it out of wealthy private ownership). Soon thereafter and well into the 1900s, development and major attractions began dominating Revere Beach Boulevard and beyond—fueled in part by easy access by the train (the Narrow Gauge) and later by ferries. The dance pavilions and ballrooms, amusement rides (among which was the Cyclone, one of the largest and most extreme roller coasters in the United States), skating rinks, resort hotels, an expansive beach, and even the Great Ocean Pier (which extended 1,450 feet into the water), entertained people flocking to the shore for a span of a century. The area eventually began to deteriorate and decline in the late 1900s, and the Blizzard of 1978 wiped out many remaining buildings and amusements. Today, visitors can enjoy the New England Sand Sculpting Festival that takes place every summer (click here for Flickr photos), as well as the draw of the beach itself, which is easily accessed by public transportation. For a more detailed historical account, along with relic pictures and postcards, see RevereBeach.com. For information on getting to the reservation, see DCR’s Revere Beach Reservation web page.

The Wharves in the North End, Boston

Leventhal Map Center of the Boston Public Library.)

In 1984, Boston took on a major revitalization of the waterfront, with a central piece being the establishment of the HarborWalk, a continuous public walkway extending nearly 50 linear miles along wharves, piers, bridges, beaches, and shoreline from Chelsea Creek to the Neponset River. Long Wharf, Rowes Wharf, and India Wharf are just a few of the wharves within the HarborWalk that are not only a fun place to visit, but are loaded with history. For more information about the HarborWalk or any of the following wharves, see the information below and the Boston HarborWalk website.

Long Wharf - Long Wharf, which was the longest wharf in North America when it was built in 1711, is one of Boston's most recognizable waterfront structures. Building a wharf long enough to extend into deep water allowed larger ships to deliver such goods as the first bananas to the United States, making this landmark a focal point of commerce for the region. As documented through the Boston Middle Passage Project, Long Wharf is also known as the port of entry where enslaved Africans disembarked from their transatlantic voyage (known as the Middle Passage) and were traded and sold. At the edge of Long Wharf, the Middle Passage Marker honors the 2 million people who perished on these voyages and the 10 million who survived. The online Boston Slavery Exhibit highlights the Middle Passage Marker and provides an overview of the history of slavery as part of the European colonization. Long Wharf was originally a third of a mile long, but continuous development and infill of the waterfront, including the construction of Atlantic Avenue in 1869, significantly reduced its length. Though Atlantic Avenue was built to provide a rail link between the northern and southern rail yards, it separated the working waterfront from the business district, diminishing the waterfront’s success. The Central Artery, built in the 1950s, further segmented the area. Efforts undertaken as part of the “Big Dig” (the Central Artery/Tunnel Project) reconnected Long Wharf to the city center and revived the area as a working commercial and residential waterfront—including boat landings, restaurants, shops, offices, a hotel, and residences—making it a popular place to visit.

India Wharf - Built in 1804 just south of Long Wharf, India Wharf was the first in the series of wharves built to respond to the newly thriving trade with China and the East Indies. India Wharf provided another deep-water anchorage and was the site of a long, stone building with 32 stores and warehouse spaces that were known to bustle with activity. As with Long Wharf, the construction of Atlantic Avenue reduced the length of India Wharf and its maintenance gradually deteriorated as shipping commerce was shifted to other areas of Boston Harbor. Demolition in the mid-1900s left India Wharf a parking lot. In the 1970s, the Boston Redevelopment Authority began the process of revitalizing India Wharf, which included the construction of the Harbor Towers, the first high-rise residential buildings on the Boston waterfront. In 2002, completion of a large section of the HarborWalk provided access around the complex and to Rowes Wharf and Long Wharf.

Rowes Wharf - The area known as Rowes Wharf was originally built by the Puritans in 1630 as a cannon-fortified position to defend and protect the harbor from threat by the English. In 1764, a developer and merchant, John Rowe, purchased the land and built a wharf to be used for commercial shipping. By 1875, a ferry connected people from Rowes Wharf to the southern terminal of the “Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad” (the same Narrow Gauge that traveled to the Revere Beach resorts). Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, shipping commerce continued to dominate the Rowes Wharf area until it fell to the same fate as the other wharves—underutilization and disrepair. Revitalization in the mid-1980s brought it back to life with the construction of a $193 million mixed-use development, which includes the Boston Harbor Hotel, retail merchants, offices, and private residences, as well as a series of floating docks used for public concerts and movies. Today, the wharf also sees its share of boating and shipping with the Rowes Wharf Marina, and as a port for commuter and harbor cruise boats.

Photo Sources:

Historic Westport Flickr site

NOAA Photo Library

Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library

Wikimedia Commons