1. MPTC is not meeting the in-service and specialized training needs of municipal police departments

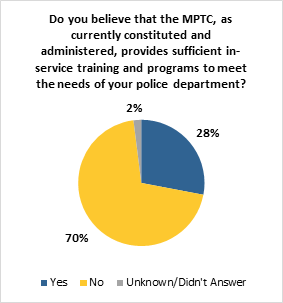

Police chiefs who participated in our survey cited various reasons why they were dissatisfied with current Municipal Police Training Committee (MPTC) programming, pointing to a low number of in-service and specialized training courses in its schedule, limited class sections, and few instructors hired to teach by the agency. A common sentiment shared by a majority of our respondents is that they do not believe that the MPTC provides enough in-service programming for their police departments, as seen in Figure 8.

a. Lack of Curriculum Diversity in Training Courses Held by the MPTC

The MPTC faces a lack of course diversity in its in-service curriculum. A majority of police chiefs, 55.8%, feel that there are courses that should be included in the standard in-service MPTC curriculum that currently are not.54 The MPTC regional academies offer a local option in-service course, where curricula is furnished by the agency based on regional training needs.55 Some courses, such as defensive tactics and legal updates, are included in consecutive training years (TYs), leaving only two or three courses offered by the MPTC that may change. As one police chief offered, there is “the same thing every year.”

|

In-Service Training |

Specialized Training |

|---|---|

|

Legal Updates (6 hours) |

Breath Test Operator Certification (8 hours) |

|

Procedures, Protocols, and Considerations for Investigations Involving Animals (3 hours) |

Basic School Resource Officer Course (5 days) |

|

Police Survival (3 hours) |

ARIDE—Advanced Roadside Impaired Driving Enforcement (2 days) |

|

Defensive Tactics Classroom and Skills (6 hours) |

Traffic Incident Management (4 hours) |

|

Local Option (6 hours) |

Crash Reconstruction (10 days) |

|

CPR (no hourly minimum) |

Advanced Crash Investigation (10 days) |

|

First Aid (no hourly minimum) |

Crash Reporting Training (2 hours; online) |

|

Firearms Training and Requalification Requirements (no hourly minimum) |

Standardized Field Sobriety Updates for Supervisors and Field Training Officers (8 hours) |

Demand remains strong among municipal police officers for courses related to mental health issues, although some of these courses were included in the MPTC’s in-service curriculum in the last two years.56 Police chiefs suggested courses such as:

- Crisis intervention;

- De-escalation;

- Mental health first aid; and

- Assisting persons with psychotic disorders.

Course diversity is also a challenge for specialized training. Curricula are developed by the MPTC, with the exception of courses that are sponsored by federal grants and/or other organizations. Discussions with policing organizations as well as survey responses from police chiefs indicated a desire for more specialized training courses from the MPTC, which can help officers fulfill their training requirements and develop skills for a particular policing assignment. The most often requested specialized training by our respondents included:

- Leadership training for higher-level officers (e.g., Front Line Leadership Training for law enforcement executives);

- Specialized investigator training (e.g., sexual assault investigators);

- Active-shooter courses; and

- Emergency Vehicle Operations Course (EVOC) training.

b. Limited Training Course Selection and Course Capacity

Although the MPTC offers multiple training courses at no cost, the MPTC’s in-service training curricula do not cover all 40 hours of mandated programming for police officers. As seen above in Figure 9, the MPTC academies currently deliver in-service training courses that have specified hours of training. Officers whose departments choose to enroll them in MPTC-conducted courses will only be able to receive a maximum of 24 hours of training, depending on academy location and available curriculum. First aid, CPR, and firearms requalification are also not guaranteed to be offered at the academies. The remaining training hours must come at the initiative of local police departments and through a variety of other available training sources. These hours can also be fulfilled with specialized training courses, but options are limited and are not always geared to the average officer’s needs.57, 58

Given constraints on budget and space, MPTC academies hold insufficient training course sections for the state’s municipal police forces. Although the MPTC’s five training academies hold in-service sessions between October and June in a given training year, the agency does not have the ability to provide training to all municipal officers with its available facility space.59 MPTC staff stated that in-service courses have a seating capacity of up to 40 officers, and few courses occur simultaneously within the same facilities.60

Based on publicly available MPTC scheduling information, the MPTC regional academies held 110 in-service training sessions in TY2019. If an in-service class holds up to 40 seats, then the agency has directly offered in-service programming to at most 4,400 officers in the Commonwealth.61 We estimate approximately 3,409 out of 14,87062 police officers work for municipalities that have their own training academy. Therefore, we believe that at least 11,461 officers are eligible to receive in-service programming through the MPTC.63 Because the agency may only seat up to 4,400 officers during training sessions, we project that at best, 38.4% (4,400/11,461) of the eligible police population attended in-service courses that were directly held by the MPTC.64

Conversely, the MPTC’s specialized training courses are held intermittently during the training year, with multiple courses being offered at local police departments instead of the regional academies. According to police chiefs responding to our survey, the low frequency of specialized training courses can be attributed to budget limitations. As a result, respondents stated they sent officers to attend training held by outside vendors like the Municipal Police Institute, an organization that conducts in-person and online courses. MPTC staff noted that specialized training offerings were contingent on financial resources from the state and the availability of federal grants.

c. Shortage of Training Instructors

According to police chiefs, the MPTC has a shortage of in-service and specialized training instructors. Respondents noted that the MPTC cancels or postpones training sessions on short notice if instructors are not available for particular courses. The MPTC may have difficulty attracting instructors, as the agency requires instructors to receive individual certifications for each course they would like to teach. The instructor certification process creates gaps in training course offerings. Police chiefs cited issues that compound this problem, such as a lack of instructor certification classes that makes it difficult for an officer to teach multiple courses, as well as requirements that demand years of expertise. Police union representatives also shared their belief with us that the process is overcomplicated and designed to allow certain individuals favored by the MPTC to become instructors. Instructor compensation may also be a deterrent for some, because MPTC instructors work on an hourly, part-time basis that is contingent on how many courses they are certified to teach. Police chiefs from the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association (MCOPA) agreed that instructor pay was insufficient, indicating that officers can earn more from detail work than from teaching; however, the MPTC has increased pay as of September 1, 2019.65

2. MPTC lacks revenue needed to fulfill training obligations, resulting in increased municipal costs

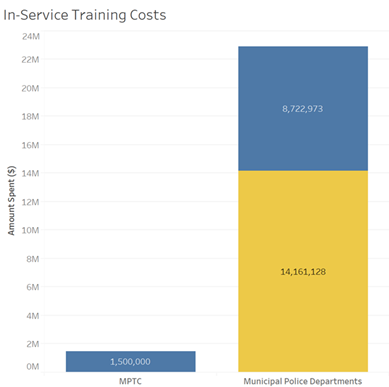

Out of its $4.9 million-dollar appropriated budget, the MPTC spent between $1 million and $1.5 million on statewide in-service training in fiscal year (FY) 2019, which includes payments for instructors, overhead, and fixed costs (such as capital and facilities).66

In comparison, we project that in-service training costs borne by municipal police departments across the Commonwealth totaled at least $22,884,101 during the same fiscal year. At least $8.7 million of this total represents municipal training expenditures on instructor fees and tuitions for programming outside of the MPTC. The remaining $14.1 million is projected to be spent by Massachusetts police departments on overtime and backfill expenditures, which are needed to pay officers their regular salaries during training and are significant drivers for municipal training costs.67 Officers who are assigned to extra duty as a result of requiring some officers to undergo training accrue overtime pay as they are scheduled outside of their normal shifts. Figure 10 shows the difference of in-service training costs absorbed by municipal departments and in-service training expenses for the MPTC.

This $22.8 million total might be higher if all police departments complied with the 40-hour requirement, and from survey responses we know that some communities offer little or no in-service training. Based on our estimates, as well as a projected municipal police force of 14,870 officers, police departments on average spent $1,539 per officer on in-service training programming in FY2019,68 while the MPTC spent just over $100 per officer on in-service programming.

There are several reasons little is spent on in-service training in the MPTC budget. The MPTC faced budget cuts in the early 2010s, which meant it suspended course offerings but still required police departments to offer 40 hours of in-service training. While the MPTC appropriation has increased from $2,286,489 in FY2010 to $4,908,930 in FY2019, there are increases in other costs such as the ongoing expenditures of the MPTC ACADIS portal and the new recruit curriculum (see Figure 7). As a result, the MPTC is forced to allocate funds that would otherwise go to in-service training to cover other types of costs. Moreover, the MPTC has a shortfall in recruit training costs (see Figure 6), where the real costs of training—between $4,000 and $4,800 per officer—are not fully covered by the tuition fee the MPTC charges ($3,000 per officer). At least $150,000 was allocated from the in-service training budget to cover the true cost of recruit training in FY2019.69

In January 2019, the state imposed a $2 surcharge on all rental vehicle contracts of more than 12 hours and less than 30 days to help finance police training through the MPTC.70 The fees from the surcharge will be placed in a Municipal Police Training Fund, and no more than $10 million may be collected for police training under statute.71 Based on revenue collections in the first two quarters of 2019, the surcharge is estimated to generate approximately between $5.7 million and $6.2 million in revenue for calendar year 2019.72

It was articulated by the MPTC and MCOPA that the vehicle rental surcharge would generate revenues close to the $10 million limit, but there is recognition now that the surcharge will collect less than anticipated.73 As a result, the surcharge is not enough to serve as a standalone and adequate source of revenue for police training. There is concern that the Legislature could eliminate the MPTC’s budgeted line item appropriation if the surcharge revenue matches or exceeds current appropriation levels, which it is on track to do for this fiscal year.

There was a consensus among surveyed police chiefs, police organizations, and the MPTC that any additional state funding should help expand training programming. The MPTC indicated its highest priority was to create further training opportunities for officers from the rental vehicle surcharge revenue. This is consistent with the feedback from survey respondents who indicated that the MPTC does not provide enough in-service programming.

3. MPTC rules, regulations, and statutory language are hard to find, unclear, outdated, and limited

There is little guidance on how to bridge the gap between what the MPTC provides in its courses and the required 40 hours of in-service training the municipalities must provide. Moreover, the statutes that govern police training lay out even more requirements than those that are met by the MPTC. On the MPTC website, the agency provides comprehensive information on new recruit training.74 At the same time, information about in-service training is limited, as course offerings, curriculum updates, and opportunities to fill the training requirement are found within MPTC meeting minutes and the Chiefs Newsletter.75

One important aspect of in-service training notably omitted on the MPTC website is a page that documents statutory training requirements that were set by the Legislature. In total, there are six statutes that impose in-service requirements that municipal officers have to meet, as well as four other statutes that suggest optional items.76 For a complete list of statutory training requirements, see Appendix E. Other statutes requiring training for all municipal police officers, such as CPR and first aid training, do exist, but do not specifically give responsibility to the MPTC.77

Some provisions of the Massachusetts General Laws require the MPTC to prepare and deliver courses, but others seem to only require the MPTC to make a curriculum available and let the responsibility to deliver training fall on the local police departments. There are provisions that recognize the lead role local police departments play in scheduling and compensating officers for time spent on in-service training, but place a burden on the individual officers to attend the required trainings. The most recent requirements set by statute were through the 2018 Criminal Justice Reform Act, where some elements from the legislation were used in the in-service curriculum for TY2019, but not all.78

Other misconceptions related to in-service training include whether or not the MPTC has an approval process for training courses from outside providers. In the last two training years, the MPTC allowed any police-related training, regardless of the provider and whether it is online or classroom-based, to be counted toward officers’ 40-hour training requirement.79Previously, in-service and specialized courses had to either use MPTC curricula and/or have approval from the MPTC as elective courses. According to police chiefs, this process was not commonly known. Some respondents in our survey managed to seek approval but received course rejections, while others attended trainings from outside vendors without any MPTC approval at all.

4. Lack of accountability for tracking & meeting training requirements due to lack of incentives

There is no current process to ensure officers’ and departments’ compliance with the 40-hour annual requirement for in-service police training. According to the MPTC, there is a lack of enforcement of the in-service requirement, and a concern that violations are common and go unsanctioned.80 Current law requires police departments to offer training, which the officers must complete or risk losing their employment (the decision solely at the discretion of the appointing authority).81 Massachusetts is one of four states that do not have some form of police licensure or certification such as those in a Police Officer Standards and Training (POST) system, as detailed below. Instead, the Commonwealth relies on statutory standards for entry into the policing profession, the MPTC for training oversight, and municipal police departments for the delivery of most training.82 Massachusetts also relies on local police agencies to interpret those standards and to exercise their discretion for dismissal of police officers, consistent with collective bargaining agreements and applicable civil service regulations.83

The MPTC is currently implementing a database system, known as the MPTC ACADIS portal, which will track the training hours logged by sworn officers at the MPTC-operated academies. Police chiefs and officers have the capability to register for in-service and specialized training courses held at the five MPTC regional academies, as the database is the only avenue to sign up for course sections. Through the system, police chiefs are able to see which of their officers attended MPTC-conducted courses for the current training year and can schedule officers who have not. However, police academies that are not run by the MPTC do not have permission to input their in-service course information and record enrollment and attendance. The same restriction applies to in-house training done by municipal police departments. While the ACADIS database has the capacity to document officers’ compliance with training requirements, the MPTC staff has not finished implementing the system to allow for robust tracking of compliance.

When we asked municipal police departments how many hours of in-service training they provided for their officers, 13 departments indicated they did not fulfill the 40 hours of in-service training, and 4 of those departments did not provide training at all. We project, based on these survey responses and the state’s population, that there could be as many as 30 municipal police departments across Massachusetts that are not meeting the in-service mandate, and as many as 9 of those departments may not have completed in-service training activities at all.84

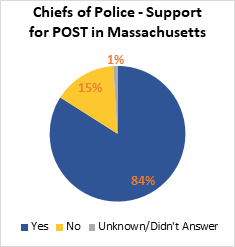

However, training accountability issues could be resolved if the MPTC transitioned into a POST system—a system that is supported by an overwhelming majority of police chiefs in our survey, as seen in Figure 11. POST systems incorporate three main functions:

- setting minimum standards for police recruitment;

- setting standards and curricula for police training and programs; and

- setting standards for maintenance of police licensure or certification.

This form of central accountability helps move forward the goal of professionalism in policing, given the public interest in a well-educated and well-trained police force. POST also allows departments to track fired and problematic officers to make sure they are not unknowingly hired when leaving one department for another in the same or a different state.

Police chiefs who were supportive of a POST system believe that the system would increase uniformity, standardization, transparency, and professionalism within police training. Some police chiefs saw the potential for departmental oversight through POST, ensuring statewide compliance with minimum standards and clearly defined regulations. Respondents cited varied interpretations of training materials that lead to inconsistent training statewide and hoped to resolve this variation with the implementation of a POST system, which, through centralization, increases consistency among instructors and training.

We also found consistent support for Massachusetts becoming a POST state from conversations with stakeholders outside of law enforcement, such as legal advocates and academics. Advocates for police accountability cited centralized authority over police training, as well as professional licensure and certification, as reasons they support such a system.85 Academic experts on POST offered specific examples of police officers who abused their powers but were hired by another law enforcement entity because their state did not have a POST system.

Further, experts provided us with information demonstrating that states with stronger oversight and accountability requirements, especially those in the southeastern United States, tend to decertify more officers. As of 2018, 30,000 officers from 45 states have been decertified.86 According to a 2015 survey on nationwide decertification practices, 44 states decertified 956 law enforcement officers that year, with the most common reasons being felony convictions and officer misconduct.87 In the absence of a POST system, experts suggested that the MPTC or municipalities incorporate use of the National Decertification Index into their operations to prevent a local police department from hiring a decertified officer from another state.88 A POST system with centralized training standards and recordkeeping could help address concerns contained in the legal analysis in Section 2 (“Liability for Failure to Train”) of this report.

POST recommendations were most recently included in prior state reviews of police training and commission reports from 2007 and 2010, and have the support of MPTC staff.89 Since the 2013–14 Legislative session, two distinct legislative proposals have been filed to transition to a POST system, although neither has advanced to the floor for a vote.90 However, we have been informed by leadership within the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS) that it has an internal working group currently studying recommendations for POST legislation.91

Nevertheless, we found that police union representatives from the Massachusetts Police Association (MPA) and the Massachusetts Coalition of Police (MASSCOP) were opposed to a POST system, as they felt such a system would push liability for not meeting the training requirements onto officers.92 However, police departments are responsible for scheduling officers for training that meets MPTC requirements, and officers are held accountable for completing that training. A POST system would allow municipalities to track officers, their training, and their disciplinary histories. Additionally, a POST authority would be able to track whether departments and officers are in compliance with training requirements or have failed to meet standards.

5. Stakeholders from law enforcement find current MPTC facilities inadequate for training needs

The MPTC operates several academies throughout the Commonwealth but does not own any of the academy buildings. Instead, there are multiyear leases or intrastate transfers that are coordinated with the academies’ respective municipalities, higher education institutions, or the state. The agency spent nearly $300,000 to lease these facilities in FY2019, not including the cost of heat and electricity, equipment, technology, and maintenance.93

A major concern among our survey respondents was the actual quality of the current facilities, especially when the facilities are used for both in-service and recruit training. Aging buildings are not modernized to current needs and do not have space for dormitories and hands-on training, and most lack a gymnasium or showers for physical fitness training. The academies also lack additional classrooms to conduct more in-service training sessions, especially when some sessions run concurrently with recruit training courses.

Survey respondents, as well as members of MCOPA and police union representatives, suggested a variety of resources for the MPTC to provide in a comprehensive facility such as EVOC space, a firearms range, and a pool for water rescue training.94 One respondent police chief stated that “[f]acilities are completely inadequate . . .,” while another suggested that a comprehensive facility would include “dormitories, driving track, firearms range, water exercise, simulation houses, classrooms, gym facilities, etc.”95 The amenity police chiefs requested most often in our survey was range space to hold firearms requalification training (12 respondents). Police chiefs from MCOPA expressed that the academies needed updated equipment in order to accommodate officers in training in a manner that supports professional policing.96

Concern about travel distance to academies was also expressed by chiefs from western Massachusetts and the Cape Cod region. Police chiefs remarked that the distance their officers have to travel from their departments to a police academy for training is prohibitive, making travel time as long as two hours or more. As one chief said, simply, “MPTC training facilities are poor, as well as the locations.” Because these regions do not have a conveniently located MPTC regional academy, these concerns have led communities to open their own facilities. These facilities are authorized by the MPTC rather than being MPTC-operated, although they are mainly used for recruit training.

Some respondents suggested that training could improve with a single, centralized facility with necessary resources instead of multiple regional facilities. Looking at the MSP Massachusetts State Police academy as a model facility, this may be a more fiscally responsible option than running several academies and with different sets of staff. Recent MPTC board meeting minutes suggest that police chiefs are supportive of a centralized facility for recruit training, while retaining the regional academies for in-service training.

| Date published: | November 18, 2019 |

|---|