1. Municipal Police Training and the Municipal Police Training Committee: An Introduction

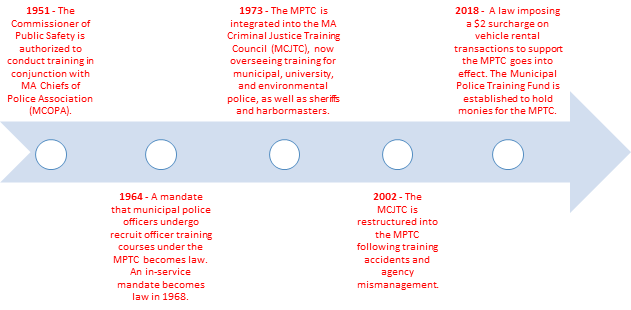

In recognition of the public interest, Massachusetts has an extensive system of police training that starts with the new recruit and continues through all the active years of veteran officers. The annual requirement for in-service training represents a substantial commitment to professional policing and requires a collaborative effort between state officials and local governments. Prior to the 1960s, police training in municipalities was held inconsistently and varied programmatically in the state. In order to establish a statewide training program, the Commonwealth authorized municipal police training in 1951, but training was voluntary and unstandardized.1 Therefore, the Municipal Police Training Council was created in 1964 to regulate training and established requirements for officers to attend uniform training courses.2 In the present day, the MPTC (now a committee) is a part of the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS) and is administered by an executive director and a committee of voting and advisory/non-voting members.3 In addition to providing training, the agency also regulates police academies across the state, develops curricula, establishes regional facilities, and sets qualifications for instructors.4 The structure of the MPTC is further detailed in Appendix C. The MPTC went through a change of leadership in July 2019 through the introduction of a new executive director acting in an interim capacity.

2. Legal and Legislative Analysis

Every person who is hired as a police officer has to meet basic qualifications. According to Massachusetts statute, officers must be at least 21 years of age and have a high school diploma, a GED, or three years of service in the armed forces.5 A new officer must also be a citizen in possession of a valid driver’s license,6 cannot have been convicted of a felony,7 and cannot smoke tobacco products.8 Depending on the municipal police department, officers also have to pass a written exam and complete both an interview and a background check.

New Recruit Training

Before they are allowed to exercise their police powers, all newly hired full-time officers in Massachusetts are statutorily required to attend a 20-week recruit officer course (ROC) approved by the MPTC.9 New recruits must also pass a physical aptitude test, undergo a comprehensive medical exam, maintain medical coverage throughout their time in recruit training, and have a cruiser to use for one week of training per MPTC regulations.10 While recruit police officers are attending the ROC, the officers’ sponsoring departments are required to pay wages commensurate with the positions to which the recruit officers were appointed plus reasonable expenses.11 New full-time recruits also pay tuition to attend the police academy, although many municipalities reimburse this expense. Recruit academy tuition at the MPTC academies costs $3,000 per officer as of 2018, funds which go directly to the MPTC.12

In-Service Training

In addition to completing the ROC, police officers of all ranks, including reserve and intermittent officers, are required to attend a 40-hour annual in-service training curriculum assigned by their department and approved by the MPTC.13 The specific trainings are determined by the MPTC on an annual basis at a monthly board meeting.14 Police officers who receive appointments to higher ranks must also complete other supervisory training determined by the agency.15, 16 While police officers are attending in-service training courses, their respective police departments are required to pay them their salaries and other reasonable expenses.17 It should be noted that Massachusetts has one of the highest hourly requirements for in-service training in the nation.18

Specialized Training

Although it is not a training requirement, the MPTC also provides specialized training to officers at no cost (examples are shown in Appendix F for training years 2019 and 2020). Unlike in-service training, specialized courses are intended to further the professional development and leadership of a police officer by improving a particular skill or preparing them for a specific policing role (e.g., school resource officers). Specialized topic areas vary each year based on availability and state/federal funding.19 Specialized courses can be included in the in-service training program of individual officers by local police departments to meet the mandated 40-hour requirement, although they are more intensive than in-service courses. These courses are also available through other organizations, which the MPTC occasionally announces on their website, but unlike the MPTC’s offerings, these courses tend to have fees.20

Other Legislative Requirements

Although the MPTC has generally broad statutory discretion to design the recruit officer curriculum and in-service training curriculum, various statutes require the MPTC to develop specific curricula for police officers in Massachusetts. For example, the MPTC must develop courses relating to domestic violence, bicycle safety enforcement, and bias-free policing. Some statutes require the agency to develop courses and guidelines for the recruit curriculum, the in-service training curriculum, or both. There is no mandate, statutory or otherwise, that officers must take training from the MPTC, but they must be assigned by their department to training courses they are responsible to attend. Appendix E has a detailed list of these statutory requirements.

Liability for Failure to Train

One other consideration in curriculum development is judicial case law. In City of Canton, Ohio v. Harris (1978), the U.S. Supreme Court held that municipalities can be liable for constitutional violations under the Civil Rights Act of 1871, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, when a municipal policy or custom causes a constitutional violation. 21, 22 The Court held that municipalities can be held liable for constitutional violations when “the failure to train amounts to deliberate indifference to the rights of the persons” that the municipal employees come in contact with. 23 In order for a municipality’s failure to train to rise to a level of a municipal policy, the failure to train must constitute a deliberate or conscious choice by a municipality.24 To establish deliberate indifference, the party bringing the lawsuit must show that the need for training was obvious and the lack of training was highly likely to result in a constitutional violation.25] However, under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, it is not sufficient to merely show that a policymaker’s actions were attributable to the municipality. In order to establish municipal liability, the municipality must be shown to have been the moving force behind the constitutional injury.26

In Canton, the Court provided two examples of a municipality’s deliberate indifference standard liability. First, the Court stated that a need for training could be so obvious that the failure to train constituted deliberate indifference. The example the Court provided was a municipality that armed its police force in part to assist police officers in arresting fleeing felons.27 The Court stated that in this example, the need to train officers in the use of deadly force is so obvious that failure to do so could constitute deliberate indifference to the constitutional rights of citizens.28 Second, the Court stated that deliberate indifference standard liability may be established by showing a pattern and practice of constitutional violations. The Court reasoned that a pattern of similar constitutional violations could have made the need for further training so obvious to municipal policymakers that not providing further training would constitute deliberate indifference.29

Moreover, in Commonwealth v. Vaidulas (2001), the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) outlined other potential consequences for police officers who are not trained to mandatory standards. In its opinion, the SJC affirms that the absence of training may be used to impeach an officer during trial and that an officer who fails to complete the requisite training satisfactorily is subject to “removal by the appointing authority” per G.L. c. 41, § 96B. The SJC adds that “[t]he Attorney General also may seek removal pursuant to G. L. c. 249, § 9,” which allows civil actions “against a person holding or claiming the right to hold an office or employment” compensated by the state or a municipality. Further, the SJC stated that “[w]here an individual is harmed by inappropriate, inadequate or negligent training of police officers, the appropriate remedy lies in a direct suit against either the supervising authority or the municipality under the Massachusetts Tort Claims Act or pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983,” the federal law allowing civil actions for violations of civil rights.30

These cases imply that officers must constantly be instructed on emerging issues or they will not be able to engage in effective policing and will put their communities at risk for liability. Without relevant and timely MPTC courses, such as the legal updates course, an untrained officer’s conduct may put their own career in jeopardy.

3. MPTC Training Sources

MPTC-Operated Police Academies

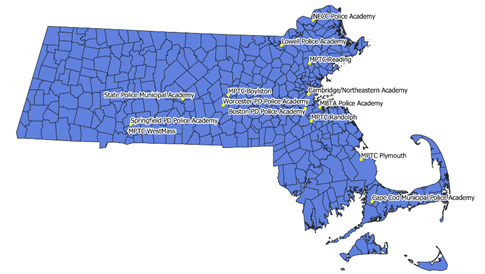

The MPTC currently holds recruit and in-service police training in five police academies, as seen in Figure 2.31 Within these locations, the agency is responsible for matters related to registration and enrollment, as well as collecting tuition for recruit training. The academies are small in capacity, with most having two or three classrooms for police officers. MPTC-operated academies require certified training instructors, who are contracted at a rate of $50 per hour (increased from $40 per hour on September 1, 2019), but MPTC staff noted that volunteers also help instruct at no cost.32 All instructors must be recertified every few years to teach particular courses and must have years of policing or professional experience before seeking certification.33

MPTC-Authorized Police Academies

There are other police academies that are MPTC-authorized, but without MPTC oversight in their operations, applications, and tuition fees. As displayed in Figure 3, these academies are usually located and operated by police departments in larger municipalities, including Boston, Lowell, Springfield, and Worcester. Other authorized academies include the Cambridge/Northeastern Police Academy, the Cape Cod Municipal Police Academy, and the Northern Essex Community College Police Academy, as well as facilities for the Massachusetts State Police and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Transit Police.34 These academies set their own dates for recruit police training, but are not required to hold in-service and specialized courses. For example, the Springfield police academy only holds in-service and some specialized training for its own municipal officers.35

Other Training Sources

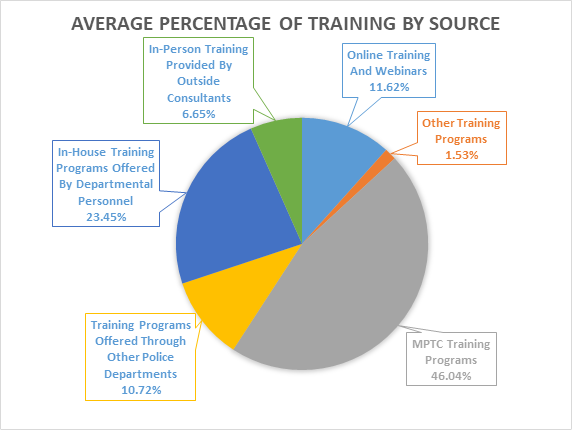

In addition to the MPTC, many police departments rely on other police departments and outside training sources to supplement academy resources. As a part of our research, we conducted a survey which elicited responses from 138 municipal police departments on their perceptions of state-mandated police training. Boston, which maintains its own police academy, also responded to our survey.36 As depicted in Figure 4, municipalities on average use the MPTC for about 46% of their total training programming, with other sources making up the majority.37 The figure depicts responses from police departments, where all are counted equally and not weighted by municipal population or numbers of sworn officers. As shown below in Finding 1, the constraint on MPTC capacity results in its direct delivery of training to less than 40% of police officers outside the large communities that run their own academies.

According to our survey respondents, police departments frequently use their own officers to hold training in-house (used by over 90% of municipalities) or seek training from other police departments (used by over 55% of municipalities). For instance, Lowell and Worcester set aside a small number of class seats for outside departments for in-service training.38

Organizations in the nonprofit and private sectors also provide police training. At least half of our surveyed departments used outside vendors for training, including organizations such as the South Suburban Police Institute and the New England Law Enforcement Training Center.39 By far, the largest and most commonly used organization is the Municipal Police Institute (MPI), which provides MPTC-authorized online in-service training.40 However, departments have to pay fees to MPI and other outside training sources, whereas training through the MPTC is tuition-cost-free.

4. Finance

State funding for the MPTC currently consists of an annual appropriation by the Legislature, as well as retained revenue from fees charged to municipalities for new recruit training. The MPTC currently receives appropriations through the state budget for in-service training under line item 8200-0200. Budgeted state appropriations for the MPTC, seen in Figure 5, come from the General Fund and the Public Safety Training Fund (PSTF).41 The PSTF allocates money to the MPTC from a $5 surcharge on motor vehicle violation fines, while the General Fund covers remaining revenue.42 This PSTF funding is transferred into the Municipal Police Training Fund (MPTF), along with money from the excise tax on marijuana sales, private gifts, and interest on the funds. It should be noted that funding for the operations of the Cannabis Control Commission and the Department of Agricultural Resources related to regulation of marijuana production and distribution are the highest priorities for proceeds from the marijuana use and distribution statute. Therefore, police training is one of several potential recipients of money, including community or school based grants to combat substance abuse, as well as funds to support public safety, the Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund, and programming for restorative justice and prison diversion. As such, it is not anticipated that money will flow to police training from this source.43 During fiscal year (FY) 2019, the MPTC received $4,908,930 in state appropriations (not adjusted for inflation).44 In addition to these funds, the MPTC is authorized to collect up to $10 million from a $2 surcharge imposed on all rental vehicle contracts of more than 12 hours and less than 30 days, as a part of the MPTF.45

|

Fiscal Year |

Line Item Appropriations |

|---|---|

|

FY2019 |

$4,908,930 |

|

FY2018 |

$4,837,750 |

|

FY2017 |

$4,687,118 |

|

FY2016 |

$5,132,844 |

|

FY2015 |

$4,937,625 |

|

FY2014 |

$3,287,968 |

|

FY2013 |

$2,475,378 |

|

FY2012 |

$2,500,378 |

|

FY2011 |

$2,476,460 |

|

FY2010 |

$2,286,489 |

The MPTC also receives and spends between $200,000 and $300,000 of federal funding from EOPSS’s Office of Grants & Research each year, which is separate from the agency’s budgeted appropriation.46 The bulk of this federal funding comes from Highway Safety Division grants, which help pay for specialized training programming.47

Funding for recruit officer training is also available from a retained revenue account, under line

item 8200-0222.48 The MPTC is permitted to collect up to $1.8 million in tuition fees for recruit training in its regional academies. Set in FY2015, the $1.8 million is the highest the retained revenue ceiling has been raised. As shown in Figure 6, the MPTC has never collected enough recruit revenue to hit this limit.

|

Fiscal Year |

Retained Revenue Collected |

% of Retained Revenue Ceiling |

|---|---|---|

|

FY2019 |

$1,012,530 |

56% |

|

FY2018 |

$1,021,198 |

57% |

|

FY2017 |

$1,229,964 |

68% |

|

FY2016 |

$1,212,792 |

67% |

|

FY2015 |

$1,550,485 |

86% |

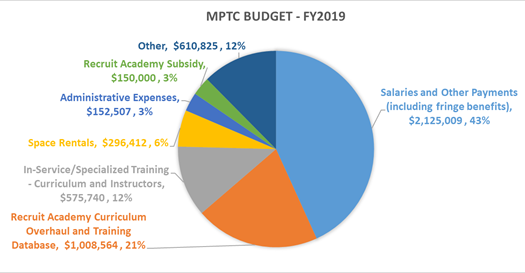

Much of the MPTC budget goes toward operating costs such as salaries, facility lease payments, overhead, and subsidies for recruit training, as seen in Figure 7.49 When asked to include a prorated share of fixed expenses, MPTC staff estimated that 30% to 35% of expenditures are allocated to in-service training. Therefore, annual spending on in-service training by the MPTC is estimated at $1 million to $1.5 million.50

The MPTC also recently added additional costs in the category of “Recruit Academy Curriculum Overhaul and Training Database” to its budget. The costs include a new recruit officer curriculum developed by a third party, costing the agency at least $100,000 a year since FY2015,51 and the creation of a new database (MPTC ACADIS)52 to track officers’ completed training, costing $700,000 each year.53

| Date published: | November 18, 2019 |

|---|