Habitat management and restoration priorities

The Biomap Habitat Restoration Resource Center identifies 36 broad habitat types occurring in Massachusetts. Some of these habitats are particularly important for Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) identified in the State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP), including over 400 animals and plants listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA). Some of these habitats are particularly vulnerable to stressors such as climate change, changes to hydrology, invasive species, or disruptions of other natural processes, making them dependent on habitat restoration and management.

Habitats supporting the largest numbers of Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN):

(ranked from highest to lowest, weighted by global rarity and MESA status)

- Dry woodlands & barrens

- Dry grassland & heathlands

- Riparian & floodplains

- Calcareous wetlands

- Fresh marshes & wet meadows

- Rock outcrops, cliffs, & talus

- Acidic peatlands

- Coastal plain ponds

- Northern hardwood conifer forests

- Forest swamps & seeps

- Oak forests & woodlands

- Tidal wetlands

- Coastal beach & dune complex

- Gently sloping cool rivers

Habitats most vulnerable to stressors:

- Calcareous wetlands

- Gently sloping cold streams

- Gently sloping cold rivers

- Tidal wetlands

- Riparian & floodplain

- Coastal plain ponds

- Marshes & wet meadows

- Oak forests & woodlands

- Gently sloping cool streams

- Steep cold streams

- Shallow drainage lakes & ponds

- Gently sloping cool rivers

- Dry woodlands & barrens

- Dry grasslands & heathlands

This list was developed by MassWildlife based on seven criteria: wildlife connectivity, impacts of human land use, sensitivity to exotic invasive species, climate threats, long-term variability in hydrology, sensitivity to or need for restoration of overstory canopy, and the need for episodic disturbances. These habitats often tend to be in relatively poor condition due to their vulnerability to stressors.

Priorities for restoration or management

Based on the above assessment of rarity and vulnerability, habitats were grouped into five tiers of priority for habitat restoration and management.

| Priority Level (Tier) 1 | Priority Level (Tier) 2 |

|---|---|

| Dry woodlands & barrens | Acidic peatlands |

| Calcareous wetlands | Coastal beach & dunes |

| Coastal plain ponds | Gently sloping cool rivers & streams |

| Gently sloping cold rivers & streams | Fresh marshes & wet meadows |

| Riparian & floodplains | Oak forests & woodlands |

| Dry grasslands & heathlands | Steep cold rivers & streams |

| Tidal wetlands | Steep cool streams |

These tiers do not necessarily describe the relative importance in Massachusetts of any given habitat type. For example, some very important habitats such as mature forest may require little management. Furthermore, the determination of which habitats to manage for should be based on landscape context and the physical resources present. Managing high quality examples of habitat types that are not represented in these top two tiers may be very high priority for specific landowners at specific sites and landscapes and can have great conservation value (e.g., maintaining a cultural grassland or reducing erosion in the buffer zone of a deep drainage lake).

Site planning overview

Developing a habitat restoration and management plan for a specific site is critical in determining and achieving the desired condition of the overall landscape. This process should be viewed as an opportunity to gather key stakeholders and look holistically at the site and its surrounding landscape to better understand:

- The site’s current ecological integrity

- The stressors that are interfering with that integrity

- Goals for the site based on physical elements and mission-driven values

- The best management trajectory to achieve those conditions

- The metrics to determine if the plan’s goals are being met

A management plan should present information in a way that allows practitioners and conservation partners to clearly understand:

- A vision for the site, ideally in the context of a greater landscape

- How the objectives for this site fit into that vision

- Why a certain management direction was chosen

- The proposed steps to reach stated outcomes

- Indicators for determining success or the need to adjust tactics

A good plan is more than simply a recipe of actions to be followed. It lays out the reasoning behind the selection of all desired outcomes, providing important context and explanation for the desired conditions and the actions being proposed. This enables managers and partners to better evaluate progress and adjust approaches as needed. This is the fundamental premise of adaptive management.

Initial considerations in planning

The first step in the planning process should always be to step back to take an objective look at the landscape in question. Planning should be based upon the actual characteristics of a landscape; not just on the values that a planner wants to impart onto a landscape. Where a landscape contains uncommon topographic, bedrock, surficial geology, or other physical characteristics that can support specialized habitats (i.e., priority natural communities) and rare species, MassWildlife recommends considering management or restoration of those specialized habitats first. Managing for rare communities and species will also provide habitat features for many more common species.

Where a landscape does not contain these sorts of specialized features, management for other habitat types that support more common species can be considered. Planners should understand the different natural communities and habitats found in Massachusetts, and their priority for restoration and management (see previous section) before beginning the planning process.

- What does the landscape look like, and why does it look this way? What are the underlying characteristics of the landscape and the specific site?

Consider the following:- Current vegetation composition and structure

- Bedrock, surficial geology, and soil types

- Topography (slopes, aspect, elevation)

- Landforms associated with physiographic regions (cliffs, ridges, outwash plains, etc.)

- Hydrologic regime, evidence of inundation, or soil moisture

- Land use history, disturbance regimes, etc.

- Stressors (invasive species, disrupted ecological processes, fragmentation, etc.)

- Administrative and public access points, internal trail networks, roads, rights-of-way, and infrastructure

Special resources typically include rare or highly specialized species, exemplary natural communities and other special natural features. There are limited locations within Massachusetts that can support priority natural communities and specialized species. Identifying any existing areas of these communities or species on the landscape, as well as locating sites that contain the features that can support such communities, are key first steps. These features—or the potential for a landscape to support these features—will often end up guiding desired outcomes and management priorities. Planners can also request site-specific information on known rare species from NHESP.

- What habitats would the landscape support under optimal conditions?

This analysis typically requires looking at the current state of the landscape and envisioning it free of stressors (where possible) and experiencing unimpeded natural processes, trying to answer the question: What natural communities would this landscape express under these optimal conditions? This requires thinking about potential vegetation expression in relation to both current vegetation and the landscape characteristics listed above. Whenever possible, decisions should be informed by high integrity reference sites.

The term “optimal” is used here to mean a result that maximizes biodiversity conservation, eliminates or reduces stressors, and provides other landowner values. It does not mean attempting to reproduce a hypothetical landscape from some point in the past, but rather evaluating which ecological processes can be restored today, given current and expected climate change and other stressors that cannot realistically be eliminated. - Understand your organization's mission, management capacity and tolerance for change.

Identifying organizational priorities and limitations up front will help in prioritizing and sequencing actions in ways that maximize short-term gains without conflicting with potential future actions if someday these limitations are reduced. For example, a small organization with limited capacity may identify a suite of important restoration and management opportunities some of which may be currently unachievable. These large-scale opportunities should still be addressed in a habitat restoration and management plan so that the immediate actions that are taken do not interfere with potential longer-term goals, and so that those more holistic opportunities are already built into an organization's thinking if capacity increases in the future. - Begin planning at a larger landscape scale.

Don’t reduce the vision or the scope of the planning exercise: even if you anticipate that there may be limitations, and even if there is only organizational support for working on one small site. By approaching the process at a full scale, you’ll be less likely to overlook important considerations or opportunities. It will also enable you to make those limitations explicit and to identify resources that would be needed to overcome them. - Seek outside consultation and take your time.

Comprehensive planning often requires the input and perspective of various disciplines, and so consultation with a variety of experts is always recommended. Depending on the site and the project, input from ecologists (to understand natural communities and potential restoration opportunities), foresters (especially if there is a timber element to the project), wildlife biologists (if there is a particular suite of wildlife to be managed for), and Conservation Commissions (to understand permitting requirements) are examples of discipline experts that can help develop the best plan for any given site. If there are species on the site that are listed pursuant to the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA), the plan is required to undergo review by MassWildlife's Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP). NHESP may be available to discuss your project with you during the development phase to help ensure that your plan does not negatively impact MESA-listed species, and in most cases, NHESP can offer advice to benefit these species while still achieving your overall management goals. - This is an iterative process

At any point in the planning process, new information may arise that requires you to return to an earlier point. This is especially true of organizational limitations, and may also occur as new natural resources are identified within the planning area, or if management actions are resulting in unexpected outcomes. Maintaining flexibility when implementing a plan is critical and is the key to adaptive management.

5 basic elements of a management plan

Element 1: Project overview

This should include:

- Location: locus map, site boundaries, and size of landscape focus area

- Landowners and managing entities

- Landscape context and general resource values (how a managed site fits into the greater area, and what resource values have been identified on that landscape)

- Target resources and general stressors (what resource you are specifically managing for, and what is negatively impacting those resources)

- Management goals (what you hope to achieve related to your target resources)

Element 2: Current conditions

This section provides a baseline overview of the composition and the condition of the landscape at the time of the plan’s development. This information is important because it allows users of the plan to better understand why decisions related to proposed management direction have been made. This context is critical for reviewers and users of the plan to understand and assess if the desired conditions stated in the plan are appropriate, and if the management actions proposed to reach those desired conditions are the best way forward. This section does not need to be overly detailed, but it does need to fully describe the current physical attributes that comprise the landscape and impact the expression of natural communities and species assemblages.

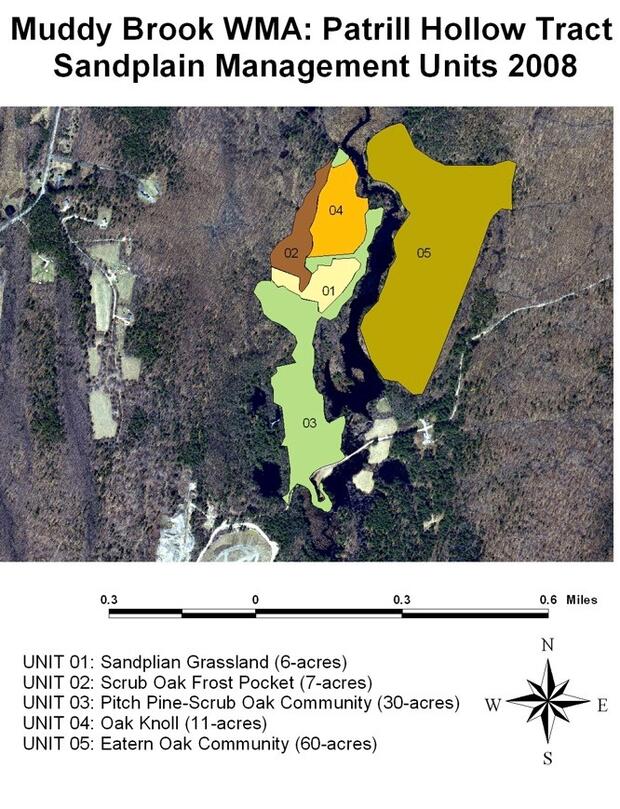

Often this section will begin with an overview of the entire focus area, and then will offer a detailed breakdown of discrete management units within the focus area. Management units are often delineated by changes in natural community cover, soil and bedrock type, topography, hydrology, roadways, ownership, or other aspects of the landscape that result in discrete compartments.

The size and number of management units will differ with each landscape. The key to determining the scale of management units is to balance the need to have units that are small enough to capture aspects of the landscape that will require different management approaches but large enough that the plan can be practically and reasonably executed. Focusing in on distinct natural communities is a good way of dividing a site into management units.

If units are based on non-ecological boundaries (ex. roads, topography, water features, property lines), the plan should note whether the units are intended to remain permanent or are expected to change as a consequence of the restoration or management actions taken.

Element 3: Desired conditions

This section contains detailed goals. These are often presented on a unit-by-unit basis, with descriptions of how the units will relate to each other. This section synthesizes the planning process and combines the conclusions of the field evaluation and mission-driven values with the realities of capacity. This element will typically begin with a description of how management will influence the greater site, followed by a unit-by-unit description of the desired vegetation structure and composition of each unit, why that outcome is desired (usually based upon the physical characteristics of the unit), what general actions are needed to achieve these conditions (more details in Element 4, below), and mention of any special resources and considerations associated with that unit. Describing natural community goals and how vegetation composition and structure will impact target species is often a very a good way of conveying desired conditions.

Determining the desired conditions of a unit is a multi-step process:

- Look at the landscape from an ecological perspective and determine how the natural community and species assemblages would express under optimal conditions. This should include consideration of historic land uses (e.g., historic aerial photos, locations of fields that could be reclaimed, homestead sites), and their potential effects on current conditions and restoration potential.

- Consider what management actions would be required to achieve these optimal conditions, and then relate this to the realities of capacity constraints and the mission and values of the overseeing entities.

- Make decisions about desired outcomes based on organizational values and capacity limitations. This is the critical step of the planning process, and is where difficult decisions about priorities, scale and ultimate land-use direction are finalized. The plan should always lay out a realistic best-case scenario, but it should also explain why optimal actions are not being recommended in every case, and why one outcome was chosen over another (limits in capacity, conflicts with mission, etc.). In many cases, this part of the planning process can end up being as much a philosophical conversation as it is an ecological conversation. Even a decision not to engage in active management is a management-oriented decision that should be documented in the habitat restoration and management plan.

Element 4: Actions and timeline

This section is essentially the work plan for the project. It lays out what specifically needs to be done, in what order, and with enough detail so that a practitioner who is not familiar with the project can still execute the plan and achieve the desired results.

For more complex projects, developing the work timeline becomes an especially critical step. This requires an understanding of how multiple actions across multiple units may impact one another, as well as thinking through priorities, realistic funding sources (including partial and full funding), and contingencies as the plan unfolds. It is important to remember that even when units seem to be separated by space across the landscape, and that actions may seem to be separated by time, the actions are still impacting one another in relation to the greater landscape, the greater project, the natural resources in the area, and the managing organization and its neighbors. All actions should always be considered in relation to all other actions. Important considerations include:

- Scale: make sure that a work plan doesn’t get ahead of capacity

- Refugia: make sure that enough viable habitat is always available to offset the temporary disruptions caused by management actions

- Sequence: make sure that actions are proposed in a logical order that facilitate [not impede] the next action

- Seasonality: consider how seasonal timing may impact the work, the species present, and other users and neighbors

- Resources and budget: make sure that actions are planned to parallel the anticipated availability of funding and labor

- Incremental gains: make sure that plans are sequenced so that there will still be a positive conservation outcome even if a project is discontinued before completion

- Landscape context: How does the action relate to nearby lands and habitat types? Does it build on existing habitat types? Could it supply a novel habitat type for the area? Is refugia available on nearby properties?

Though specific management actions (ex. forestry, mowing, fire, etc.) are often the focus of this section, all actions necessary to bring a plan to completion need be included. Critical considerations such as obtaining landowner permissions, securing funding sources, acquiring required permits, and setting a timetable for project assessment are all important elements.

As with all sections of the plan, unnecessary complexity should be avoided: a good plan will find the balance between having enough detail to clearly convey the intention of an action without obscuring that intention with unneeded information. With this in mind, technical plans used to facilitate specific restoration and management activities (ex. prescribed fire plans, forest cutting plans) should be referenced and appended to the habitat restoration and management plan, but the details of these technical plans should not be written into to the body of the habitat restoration and management plan.

Key considerations when developing a workplan include:

- Determining the scale to describe actions (either by unit, unit groups, or the landscape, depending upon the situation).

- Providing enough detail for each action so that a practitioner can accomplish the action.

- Describing how negative impacts to regulated species and resources will be minimized.

- Setting not only the sequence of events needed to accomplish each action, but also the sequence of actions for each event.

- Briefly describing what a successful action will look like.

- Providing triggers for adaptations and contingencies, if possible.

- Including acknowledgement of long-term resource commitment and monitoring needs.

Often this element of a plan is divided between text providing the detailed description of actions, followed by a graphical timeline of actions. In some cases, it may be helpful to also include a projected budget.

Of course, there will always be unexpected outcomes when executing a plan, and this element should also make clear that the plan is to be adaptive. A practitioner will always be better equipped to make the right decisions in overcoming unexpected outcomes and challenges when the preceding elements of the plan explain not only the desired outcomes, but why those outcomes are desired.

Element 5: Monitoring, objectives, and adaptation

The execution of management actions is never the end goal of a management plan: management actions are simply the tools used to achieve desired outcomes. This underscores the importance of the setting clear goals and objectives in the Desired Conditions element of the plan, as the true conservation outcome of a restoration and management project will be determined by how the landscape responds to the management actions in relation to these stated goals and objectives. This is where monitoring come into play.

Goals and objectives are dependent upon monitoring, because without monitoring, there will be no way of knowing if a project has achieved the stated goals. And without monitoring, there will be no way of determining if a management action is performing as expected, or how to adapt if it is suspected of underperforming. Therefore, monitoring should be a consideration of your project from the very onset of planning.

Establishing baseline documentation for a project is one of the most important—and often one of the most overlooked—aspects of a project. After an initial size-up of a landscape has been completed and general goals are established, thoughts should quickly turn to monitoring. There will never be a second chance to establish a baseline once management actions have begun, and meaningful objectives are very difficult to establish without some baseline related to those objectives.

Vegetation will almost always be a key component to any monitoring regime. In order to track changes and measure the success of a restoration project, a good baseline of representative vegetation characteristics is key. (Vegetation monitoring resources are provided in the resources section.) Species composition and structure are typically the primary focus of a vegetation monitoring program, and the complexity of the monitoring program should reflect several considerations:

- What is necessary to track change?

This will vary from project to project and from organization to organization. A more complex monitoring program may provide more information, but a complex monitoring program may also become an impediment to actual monitoring. A realistic balance needs to be struck, and in general, the question of complexity could be framed as how simple can a monitoring scheme be while still providing the power to be meaningful? That answer may sometimes lead to a complex monitoring scheme, but in many cases, a relatively simple scheme will be all that’s necessary. Often simple schemes that measure estimated percent cover by species at various strata within set plots will suffice to show change over time. - What is representative?

This question becomes increasingly complex as the size of the patch being managed increases, and especially in larger patches, the answer really comes down to understanding how the monitoring will relate to evaluating your goals and objectives. How many plots or transects are needed? Should they be randomly placed or gridded? These questions are too complex to answer here, but it’s a critical consideration, and one that may require outside assistance for larger, more complex projects. - Looking to the future

You or your staff may have the expertise or capacity to employ a more complex and robust monitoring system right now, but will this always be the case? Restoration and management projects should always be viewed as indefinite and ongoing propositions, and so think about what will be achievable in the future. Overbuilding a monitoring scheme may eventually result in that scheme being abandoned. - Photo plots

Regardless of what vegetation monitoring scheme you chose, a simple element of photo monitoring should always be incorporated. Fixed plot photo monitoring is simple, the visual change can be interpreted by just about anyone, it provides invaluable historical context, most anyone can do it, and it can sometimes provide unanticipated information in the future. A simple photo monitoring scheme can be found here: (link to the document in this folder). - Monitoring frequency

The timing of monitoring frequency will depend on the management action and objectives being measured. In general, the monitoring of restoration projects should occur at a relatively high frequency (annually) early during a project, but as time passes and the landscape stabilizes, monitoring frequencies can expand. The key is to monitor frequently enough to detect and react to change, but not so frequently that the individual monitoring efforts are not meaningful.

While vegetation monitoring will almost always be included in a project’s monitoring scheme, monitoring other values will provide additional insight into how your project is progressing; especially if your goals and objectives relate to more than simple vegetation cover. If your objectives relate to a specific species or suite of species, then obviously monitoring those species on some level will be important. However, even monitoring species not explicitly called out in your goals and objectives can be extremely informative. Examples might include monitoring birds, moths, other pollinators, and targeted plants.

A critical aspect of managing a landscape is to know when the management activities are achieving their intended goals and objectives, and when they are not. Arguably, realizing when goals and objectives are not being met is one of the most powerful outputs that a monitoring scheme can provide. For monitoring the integrity of a natural community, building triggers into a monitoring scheme based on the presence of undesirable vegetation can be an excellent approach. For example, in a common natural community, a management action is triggered when monitoring detects invasive species. Or, in a highly specialized natural community, a management action is triggered when generalist species are detected above certain thresholds. Likewise, for species-specific objectives, monitoring should trigger close evaluation of a project when conservation targets are shown to be in decline, or when potentially non-complementary species are shown to be increasing.

Designing a clear, comprehensive, and executable habitat restoration and management plan can be a long and involved process. It can also be a very rewarding and enlightening experience that results in a deeper understanding of the landscape while bringing together partners and communities in ways that no other process can. Committing the time and effort to planning up front will ensure that a solid framework will be in place for an organization to work from far into the future, setting the stage for not only positive long-term ecological outcomes, but also providing a mission-related roadmap for the next generation of decision makers to work from ensuring that the legacy of a contemporary vision continues to grow and evolve.

Helpful resources

- Measuring and Monitoring Plant Populations

Interagency technical report, Bureau of Land Management - National Protocol Framework for Monitoring Vegetation in Prairie Reconstructions

US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Wildlife Refuge System - Vegetation Sampling Protocol for Xeric Habitats of the Northeast

Technical report prepared by Poulos Environmental Consulting LLC for the Northeast Regional Conservation Needs Program and the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. - Fire Monitoring Handbook

Fire Management Program Center, National Interagency Fire Center. - Quick Guide to Photo Point Monitoring

Natural Resources Conservation Service