Into the Hockomock: Where wildlife and stories dwell

As the leaves turn and the air cools, October beckons us to explore the mysterious and the unknown. And what better place to highlight than one of Massachusetts’s most storied and ecologically important landscapes—Hockomock Swamp Wildlife Management Area (WMA).

Stretching across southeastern Massachusetts, Hockomock Swamp is the largest freshwater wetland in the state, encompassing thousands of acres of haunting beauty and ecological diversity. Managed by MassWildlife, this vast WMA spans parts of Bridgewater, Raynham, Easton, Norton, Taunton, and West Bridgewater, offering a unique mix of scenic marshes, red maple swamps, acidic fens, and pockets of Atlantic white cedar bogs. It’s more than just a spooky backdrop—it’s a thriving natural habitat, home to at least 13 rare and endangered plants and animals.

The upland areas surrounding the swamp add even more variety, with mixed hardwood forests, patches of farmland, and stands of pine and hemlock. Lakes, rivers, and ponds—including Lake Nippenicket, the Snake River, and Gushee Pond—provide further refuge for wildlife, opportunities for recreation, and critical water resources for the surrounding communities.

In addition to its ecological importance, Hocomock Swamp is a place of cultural and historical significance. Archaeological sites in the area are known to span a period of 9,000 years. The name Hockomock comes from the Algonquin word meaning "place where spirits dwell." According to Wampanoag tradition, this swamp was closely associated with Hobomock, the spirit of death.

During King Philip’s War in the 1670s, Wampanoag warriors used the swamp as a stronghold in their resistance against English colonists. Its dense vegetation and twisting waterways formed a natural fortress and maybe even a perfect place to disappear into the mist. The story goes that English soldiers who feared the swamp’s unknowable depths gave it an ominous nickname of Devil’s Swamp.

Over the past 50 years, tales of the paranormal within the swamp have cropped up, perhaps due to the swamp’s rich history and striking landscapes. Strange lights, ghostly figures, and even monstrous beasts have all been reported in the Hockomock. Some say they’ve seen bigfoot stalking the woods; others swear they’ve encountered massive, winged beings swooping overhead. Adding to the mystery, Hockomock lies within the “Bridgewater Triangle”—a hotspot for alleged supernatural activity.

While these tales can be fun and intriguing, one thing is certain, this large natural wetland is an irreplaceable natural resource. Hockomock Swamp WMA plays a critical role in supporting wildlife, filtering water, and providing access to nature for all.

So, this October, while you are sitting around the campfire telling stories, don’t forget to talk about Hockomock Swamp, where the natural world and the supernatural seem to meet.And if you visit, don’t wander too far into the swamp when the sun starts to set…

Over 300 Acres Protected for Wildlife and Outdoor Recreation in Stockbridge

The Department of Fish and Game (DFG) and Division of Fisheries & Wildlife (MassWildlife) joined local leaders, partners, and the public to celebrate the conservation of over 308 acres of critical habitat for wildlife and outdoor recreation in the Berkshires. The new Rockdale Highlands Wildlife Management Area (WMA) protects biodiversity, boosts climate resilience and carbon sequestration, and creates new access to outdoor recreation for the community.

New board member: Kyla Hastie

Kyla Hastie, of Shutesbury, has been appointed by Governor Maura Healey to the Massachusetts Fisheries and Wildlife Board. The seven-member Fisheries and Wildlife Board supervises the Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MassWildlife) and reviews and approves regulations related to fish and wildlife before they are promulgated by MassWildlife. Hastie will serve as the wildlife biologist at-large member, replacing John Organ of Buckland.

“I am honored to serve the Commonwealth on the Fisheries and Wildlife Board, and to support science-based fish and wildlife management of the extraordinary biodiversity of Massachusetts,” said Kyla Hastie.

While Kyla has more than 28 years of fish and wildlife conservation experience, her love for nature started at a young age with baiting a hook and cleaning her catch with her father. Before joining the Board, Kyla served as the Northeast Deputy Regional Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from 2019 to 2025, and collaborated with tribal governments, nonprofit leaders, local communities, and others to protect and restore habitat while also increasing wildlife recreation opportunities. She led 750 employees to implement and enforce federal wildlife laws like the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, to manage 82 national wildlife refuges and 13 national fish hatcheries, and to administer funds through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act and Federal Aid in Sportfish Restoration Act. Ms. Hastie previously directed communications with news media, Congress, and partners. She also worked as a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Georgia, and for The Nature Conservancy developing partnerships with landowners.

"Kyla Hastie is a talented conservation leader with a unique ability to build partnerships and coalitions across boundaries. With decades of experience as a regional director, wildlife biologist, policymaker, and communications professional with the USFWS, she also brings considerable expertise building relationships with Indigenous peoples and Tribes in our region,” said Department of Fish and Game Commissioner Tom O’Shea. “As a Fisheries & Wildlife Board member, she will be a great champion of science-based stewardship, land conservation and restoration, access to outdoor recreation, and fostering meaningful involvement of all people in the care and stewardship of our lands, waters, and wildlife. We are delighted to have Kyla join us. I also want to thank outgoing Board member John Organ for his service and considerable contributions throughout his tenure.”

Kyla holds a bachelor’s degree in biology at Southwestern University (Texas) and a master’s degree in environmental science with a focus in ecology from Indiana University. Additionally, she received a master’s in public administration from Indiana University, which supported her long career working in the federal government.

“Kyla has built her career on advancing fish and wildlife conservation through science, collaboration, and a strong commitment to public service,” said MassWildlife Director Mark S. Tisa. “Her expertise as a wildlife biologist, coupled with her proven leadership at the national level, will be an asset to the Fisheries and Wildlife Board as it continues to support MassWildlife’s mission of conserving biodiversity and expanding public access for outdoor recreation.”

Kyla and her husband Keith live in Shutesbury and are avid hikers and wildlife-watchers. As a lifelong learner, she is currently completing an MBA at the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Mystery mammal skull challenge

Can you identify the mystery mammal skull below? You don’t need a psychedelic van, meddling kids, or a snack-loving Great Dane to crack this case. All you need to look for are cranial clues.

Before you start, refresh your memory of common mammals in Massachusetts.

Mystery skull

While exploring the three clues below, return back to these skull photos to try identifying the mystery mammal.

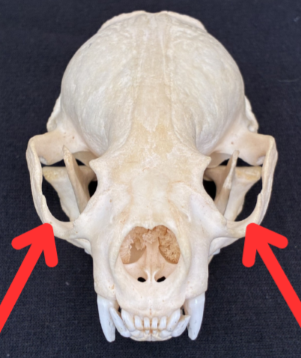

Clue #1: Eye socket location

White-tailed deer eye sockets are located toward the side of their head. This gives them peripheral vision to see nearby predators.

The location of the eye sockets (orbitals) on the skull can give insight into whether the animal is a predator or prey. This can narrow down your guess.

Prey animals, or those that are hunted by other animals, tend to have eyes located toward the sides of their head. This gives them peripheral vision, allowing them to see about 180 degrees around them so they can detect predators nearby.

This North American river otter skull has eye sockets facing forward, showing they are proficient predators of fish and other aquatic animals.

Predators, those that hunt other animals, often have eyes located toward the front of their skull, like humans. This gives the animal binocular vision, which allows them to have the depth perception needed to successfully find and catch prey.

Look at our mystery skull – Where are the eye sockets located? Do you think this animal is a predator or prey?

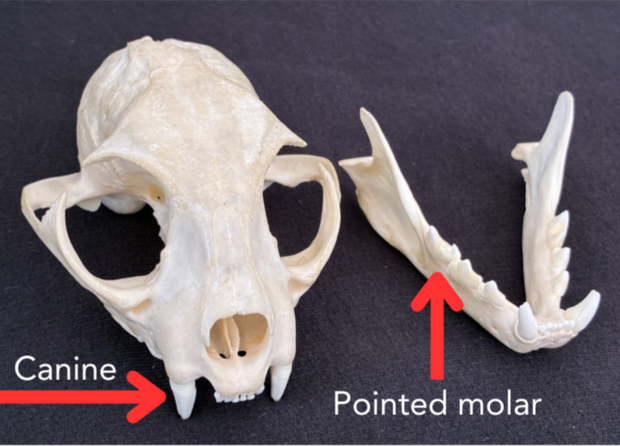

Clue #2: Tooth shape

Teeth are tools that animals use to tear apart or grind their food. By looking at the mystery animal’s teeth, you may be able to determine if the animal is a meat eater (carnivore), plant eater (herbivore), or if they eat both plants and meat (omnivore).

This bobcat skull has large canines and pointed premolars and molars for shearing and tearing meat.

Carnivores need teeth designed to catch and tear apart their food. Pointed, triangle-shaped teeth are best for this job. Carnivores tend to have pronounced canines but will often have more pointed molars too.

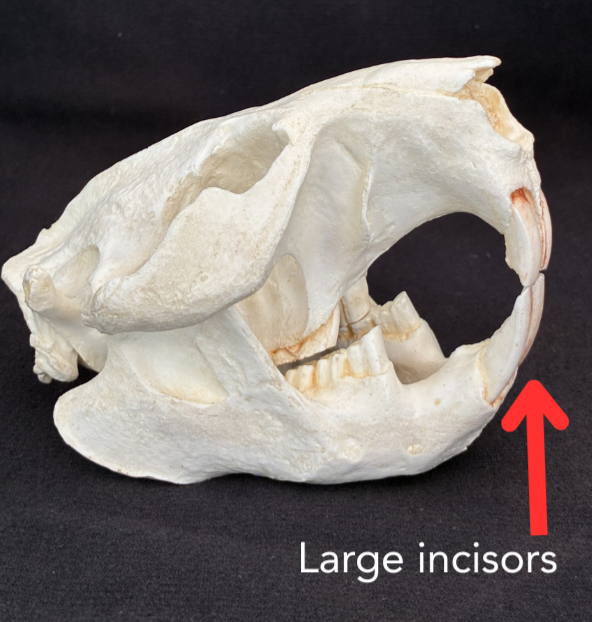

Herbivores need teeth that are suited for grinding plant material. Most herbivores do not have canines and rely on their chisel-like incisors to bite off pieces of vegetation and their flat, rigid molars to grind down their food. Deer and moose do not have upper incisors, so they use a combination of their lower incisors and a calloused pad on the roof of their mouth to bite off vegetation. Rodents, like squirrels and beavers, have large front incisors with orange enamel. While rabbits and hares are lagomorphs and not rodents, they have large front incisors but do not have orange enamel.

This beaver skull has large incisors with orange enamel and no canines. This suggests that they’re not only herbivorous, but they’re also a rodent!

Since omnivores eat both meat and plants, they need a mix of pointed teeth for tearing and flatter teeth with ridges for grinding. Think of your own teeth as an example. We have canines we use to tear into a hamburger, but we then send the food back to our flatter molars to chew.

Look at our mystery skull – What tooth shapes do you see? Do you think this animal is a carnivore, herbivore, or omnivore?

Clue #3: Snout shape and length

Canids, including coyotes (left), have long snouts that make them excellent at smelling. Felids, such as bobcats (right), have shorter snouts, hinting they use other senses, like sight, more often.

The size and shape of an animal’s snout can suggest how much the animal relies on its sense of smell. Bears, coyotes, and foxes are known for their longer noses and keen smelling abilities. Cats, like bobcats, have shorter snouts and tend to use senses other than smell, like vision, to navigate their environment.

Look at our mystery skull – Do you think the mystery animal has a long, medium, or short snout? Do you think smelling is their primary sense?

Ready to solve the mystery?

Clue #1: The skull has eyes on the front of their head. The animal is a predator, hunting for some or all its food.

Clue #2: There are both pointed canines and flatter molars with ridges. This means the animal is likely an omnivore, eating meat and plants.

Clue #3: The skull has a medium-length snout. This suggests the animal may use their sense of smell often, but other senses may be equally important.

Want another hint?

This medium-sized mammal has excellent dexterity and can turn doorknobs and open containers.

The answer is...

Raccoon! Raccoons are highly adaptable and occupy a variety of habitats, including agricultural land, forests, wetlands, and neighborhoods. As opportunistic omnivores, raccoons eat whatever is easiest to find and readily available, including insects, crayfish, crabs, mussels, turtles and their eggs, injured waterfowl, and muskrat kits. Raccoons raid bird nests consuming eggs and nestlings, and feed on plant material such as berries, nuts, and seeds. Additionally, raccoons are well known for raiding garbage cans, agricultural crops, chicken coops, and pet food left outdoors. Raccoons are active year-round and do not hibernate, although during very cold weather, they may sleep in a den for several days at a time.

Blazing a path for wildlife

For thousands of years, fire has shaped Massachusetts’ landscape and has benefited wildlife by altering different elements of their habitat. Other management techniques such as mowing, plowing, planting, or herbicide treatments may be used to achieve some habitat goals, but there is no substitute for the unique effects fire produces. Fire can benefit wildlife by affecting habitat in four major ways: shifting structure (referring to height, density and arrangement of vegetation), influencing plant composition (favoring species adapted to frequent fire), increasing food availability and nutrition for wildlife, and creating a shifting mosaic of habitats across the landscape through the variable nature of fire.

You might already be familiar with the positive impact periodic fire has on game animals like deer and turkey as well as on rare species like the frosted elfin and eastern whip-poor-will, but there is a long list of common and declining species that benefit from habitats managed with prescribed fire. Learn about a few species that may surprise you below.

Grasshopper sparrow

This bird is a state threatened and regionally rare songbird that requires large areas of sandplain grassland habitat (usually more than 30 acres). Large areas of sandplain grasslands are now rare in Massachusetts, and therefore the wildlife that need these grasslands to survive and thrive are often rare as well. Grasshopper sparrows eat, sleep, and nest on the ground. When threatened by a predator, they scurry along the bare ground between clumps of grass rather than fly. The clumps of native warm season grasses are umbrella shaped, providing overhead protection for nests and cover from predators while also offering space on the ground to move and forage. Grasshopper sparrows survive largely on insects, which are abundant in fire-managed grasslands.

Ruffed grouse

Over the past few decades, the iconic spring “drumming” echoes of ruffed grouse have dwindled across Massachusetts, partly because specific habitats this game bird requires have come to be less common. Though they use a variety of forested habitats, ruffed grouse particularly need dense, brushy shrublands and young forests between 5 and 30 years of age offering ample food and cover from predators. Currently, less than 10% of Massachusetts forest habitats contain these ephemeral habitats. Without regular disturbances such as blowdowns, cutting, or burning, these habitats quickly mature, no longer suiting our native partridge’s specific needs. Prescribed fire improves the habitat structure needed in all life phases of ruffed grouse. As chicks, ruffed grouse require a protein-rich diet of insects that are abundant in fire-managed landscapes. On recently burned areas, broods of young grouse can readily roam the forest floor, making it easier for them to find food and escape predators. As adults, ruffed grouse rely on the seeds of herbaceous plants, especially legumes, and short-lived trees and fruiting shrubs such as sun-loving cherry, aspen, and hazelnut. In pine barrens, ruffed grouse feed on the abundant nuts produced by scrub oak and hazelnut in the fall. The highly nutritious flower buds of both shrubs are available in the late winter and early spring when few other foods exist.

Bats

They may not normally be considered the poster child for prescribed fire, but fire can play an important role in ensuring good habitat for bats. Fire can be helpful to bats, including the state declining (species of special concern) eastern red bat and federally and state endangered northern long-eared bat, in three ways. Our bats feed on insects; fire-managed areas tend to produce more insects compared to areas that don’t experience fire. Because bats fly to catch their prey, the open canopy and less cluttered forest structure created by fire allows bats to navigate more easily. Many bats need snags (standing dead trees) and tree cavities for roosting; fire-managed sites tend to contain a greater number of snags and cavities than non-fire managed sites. In fact, low intensity prescribed fires are much less likely to destroy the snags or harm newborn pups than an uncontrolled wildfire.

Eastern box turtles

These reptiles have a complicated relationship with fire. Box turtles prefer to spend their time in fire-managed habitat, but they are also more susceptible to being killed in fires. Box turtles grow slowly, reaching sexual maturity around 13 years old, and some may live more than 50 years. Because of their slow reproduction rate, box turtle populations can be susceptible to large mortality events, a variable that is carefully considered when MassWildlife creates a burn plan. Fire creates habitat conditions that help improve box turtle nesting and foraging. They prefer to nest in areas with bare soil that are open to sunlight, in grassland, woodland, and in forest openings. Turtles often travel great distances, crossing dangerous roads, to find suitable nesting habitat. In fire-managed areas, turtles may find nesting areas closer to where they forage. Eastern box turtles are omnivorous, eating nearly anything including berries, seeds, leaves, mushrooms, insects, slugs, worms, and even carrion; fire helps increase the density of insects and herbaceous plants, making food more plentiful.

Native bees

At last count, 390 species of native bees have been documented in Massachusetts. The importance of native bees to the environment and to our food production cannot be overstated. Most plants with flowers depend on bees, butterflies, or moths for pollination to reproduce, and much of the heavy lifting is done by native bees. Without pollination there is no reproduction, which means that there are fewer seeds or fruits for wildlife (or people) to consume without healthy populations of native bees. Recent studies show higher bee diversity in fire-managed areas when compared to nearby unburned areas. This is not a surprise because fire-managed areas typically have higher plant diversity (especially wildflowers) than non-fire managed areas. The high production of blueberries, huckleberries, legumes, and other seeds and fruits that appear after a fire begins with flowers visited by bees. Fire promotes fresh growth and flowering in many plants and shrubs. The flowers provide food for bees, and the seeds and berries provide food for wildlife. Fire also provides for other critical parts of their lifecycle. Most native bee species nest underground in areas with plentiful sun and bare ground; a condition common in fire-managed systems. Other bees nest in narrow tunnels dug into wood. They usually use dead limbs, downed logs, or other punky or dry, rotting, crumbly wood and pithy stems that are prevalent after a fire.

Interested in learning more about prescribed fire and all of its benefits? Check out our prescribed fire webpage and our webinar Fire and Wildlife Habitat: A Natural Process and Management Tool.

Celebrate Bat Week

‘Tis the season for celebrating the flittermouse, flying fox, or most commonly known as bats! Bat week starts October 24, where bat lovers raise awareness about the need for bat conservation and to celebrate their roles in nature.

The Commonwealth is home to 9 species of bats and 8 of those are listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA). Become a bat expert by learning about each bat below, going to the film showing of The Invisible Mammal in Keene (NH), Grafton (MA), or Waltham (MA), and visiting Mt. Greylock for a bat night walk with Dr. Laura Hancock, an ecology and wildlife researcher.

Big brown bat

This long, glossy, chocolate brown fur flier is the second largest bat species in Massachusetts. With a wingspan of about 1 foot wide, they enjoy swooping into the sky and eating beetles and stink bugs. Found in all throughout continental US, they are considered habitat generalists, meaning they are okay with living in a variety of urban and rural areas.

Little brown bat

Most commonly known to humans as house intruders, the little brown bat used to be one of the most abundant bat species in the northern US. White-nose syndrome, a deathly disease caused by a fungus that naturally grows in caves, has severely impacted their population numbers. Fun fact: Upon looking closely at their fur, you can see that it is two-toned, meaning that their hair is dark at the base and light at the tip.

Northern long-eared bat

At dusk, this bat uses its long ears, long tail, and large wing membrane to fly in such a methodical way that enables them to pluck prey right off of foliage in cluttered environments. Locating the resting insects require them to use a combination of passive listening and the emission of high frequency echolocation calls. They prefer roosting in clusters of large trees, bonus points if they are hardwoods with large, tall cavities!

Indiana bat

Often confused with the little brown bat, the Indiana bat is known for having a distinctive pinkish-brown color of fur that is noticeable only under good light. They are a migratory species that only hibernate in a few select caves and abandoned mines in the US. As the name suggests, majority of the hibernation locations are in Indiana and hasn’t been recorded seen in Massachusetts since 1938.

Eastern small-footed bat

The eastern small-footed bat is one of the tiniest bats in the eastern U.S., with a distinctive black "masked" face, tiny hind feet, and a flattened skull that helps it squeeze into tight rock crevices. Like other Massachusetts cave bats, mating occurs in the fall at hibernation sites, followed by a period of delayed implantation. After a 60-day implantation, a single pup is born in May or June.

Tricolored bat

Nicknamed the ‘moth bat’ due to its weak, fluttery, erratic flight, the tricolored bat often leaves the roost at the earliest in the evening to feed. They have individual hairs on their back that are tricolored; they are slate gray at the base, yellowish brown in the middle, and dark brown at the tips. They hang from walls (not ceilings!) in the warmest parts of a cave or mine where the humidity is so high that water droplets cover their fur.

Silver-haired bat

The recently listed bat species has dark blackish brown hair with silver-tipped guard hair on its back. They are the most uncommon tree bat in the state and prefer to roost in hollow trees, crevices in rocks and cliffs, and under loose bark. Like other species of bat, they are susceptible to wind turbines, a newer threat that conservationists are trying to develop a better understanding of.

Eastern red bat

Eastern red bats are sexually dimorphic, with the males displaying a bright brick red fur and the females displaying a buffy-chestnut fur. They migrate south to Florida in the winter and have been found as far offshore as 130 miles on ships at sea! Although they are traditionally known as hardwood forest-dwellers, they have been found in a wide range of habitats, including cemeteries, orchards, and edges of lakes.

Hoary bat

The hoary bat is the largest bat in Massachusetts with a wingspan of nearly 17 inches! It has striking silver-tipped fur and can fly up to 60 mph with a strong, direct flight. Since they do not emerge until well after sunset, fly high and fast, and live singly, hoary bats are not well reported. They are usually a solitary creature, only occurring together to mate and care for their young.

How you can help bats

- Educate yourself and others about bats by learning about the variety of threats they are facing in Massachusetts and across the country.

- Help provide safe, warm roosting sites for females to raise their young. Create a bat-friendly backyard by leaving old, dead, or dying trees standing to provide natural roost sites. Or, if you’re handy, learn how to build and install a bat house.

- Support bats and other rare species in Massachusetts by donating to MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

- If you must exclude or evict bats from your home, ensure the process is safe and humane by following MassWildlife’s recommendations found in the Massachusetts Homeowner's Guide to Bats.

- Be a citizen scientist. If there is a colony of 10 or more bats on your property, use our online form to report it. Colonies may be found in trees, buildings, attics, barns, sheds, or other outbuildings. This information will be used to help conserve the state’s endangered population of little brown bats.

Watch for wildlife on the road this fall

Because fall is the breeding season for both moose and white-tailed deer, MassWildlife reminds motorists to be mindful of increased deer and moose activity, especially during early morning and evening hours. Moose, found in central and western parts of Massachusetts, breed in September and October. White-tailed deer breed from late October to early December.

Moose on the road are especially hazardous. The dark color and height of moose make them difficult to see in low light; moose eyes rarely shine like deer eyes because their eyes are above headlight level. In addition, long legs and heavy top bodies make moose very dangerous to motorists when struck. Observe road signs for moose and deer crossings and slow down. Do not swerve to avoid hitting a deer because it may lead to more risk and damage than hitting the deer. Moose are less likely to move from the road than deer, so stay alert and brake when you see a moose in or near the road.

Deer and moose/vehicle collisions should be reported to the Environmental Police at 1-800-632-8075. In the event of a deer/vehicle collision, the driver or passengers of the vehicle involved (MA residents only) may salvage the deer by bringing it to a MassWildlife Office to be officially tagged.

All outdoor users: Wear blaze orange this fall

Hunting is a safe activity. The widespread use of blaze orange has helped dramatically reduce hunting-related firearms incidents in the field. While hunters are required to wear blaze orange during certain seasons, all outdoor users who are in the woods during hunting seasons should wear blaze orange clothing as a precaution. If you're curious about the effectiveness of blaze orange, watch the short video above for an eye-opening demonstration. If you plan to enjoy the outdoors during hunting season, review these tips:

Tips for non-hunters

- Know when and where hunting is allowed. Review the 2025 Massachusetts hunting season dates. Hunting on Sunday is not permitted in Massachusetts.MassWildlife lands, including Wildlife Management Areas and Wildlife Conservation Easements are open to hunting. Most state parks and forests are open to hunting, and many towns allow hunting on municipal lands. Learn about lands open to hunting in Massachusetts. Research the property you plan to visit beforehand to learn if hunting is allowed. If being in the woods during hunting season makes you uneasy, find a location where hunting is not allowed or plan your outing for a Sunday or another day outside of hunting season.

- Keep pets leashed and visible. Place a blaze orange vest or bandana on your pet to keep it visible.

- Make your presence known. Talk loudly or whistle to identify yourself as a person. You may also consider wearing a bell. If you see someone hunting or hear shots, call out to them to identify your location.

- Be courteous. Once you've made your presence known, don't make unnecessary noise to disturb wildlife or hunting. Hunter harassment is against state law. Avoid confrontations with hunters. If you think you've witnessed a fish or wildlife violation, report it to the Massachusetts Environmental Police at 1-800-632-8075.

Tips for hunters

Hunting is among the safest of all recreational activities. You can help keep it that way by always following the 10 basic rules of firearms safety.

Wearing blaze orange is a legal requirement during some hunting seasons. Some hunters may worry that wearing blaze orange will hurt their chances of harvesting an animal. While deer are not colorblind, they lack the ability to detect colors like red and orange from green and brown. Wearing blaze orange will not matter to the deer, but may save your life.

- All hunters during shotgun deer season and deer hunters during the primitive firearms season must wear at least 500 square inches of blaze orange material on their chest, back, and head. (Exception: coastal waterfowl hunters in a blind or boat.)

- All hunters on Wildlife Management Areas during the pheasant or quail season on WMAs where pheasant or quail are stocked must wear a blaze orange cap or hat. (Exception: waterfowl hunters in a blind or boat, and raccoon and opossum hunters at night.)

Habitat management grant opens September 26, 2025

Private and municipal landowners of conserved lands can apply for grant funding to support active habitat management projects that benefit wildlife and enhance outdoor recreation opportunities. MassWildlife’s Habitat Management Grant Program (MHMGP) provides financial assistance for projects that:

- Improve habitat(s) for Species of Greatest Conservation Need, as identified in the 2025 Massachusetts State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP), with emphasis on MESA-listed species;

- Enhance habitat in ecological communities that are disproportionally susceptible to climate change;

- Contribute to improving habitat in a landscape that is high priority for biodiversity conservation; and

- Promote access to nature and outdoor recreation opportunities, such as hiking, birding, fishing, hunting, and trapping.

Although MassWildlife and other organizations have made unprecedented investments in land conservation in the Commonwealth, acquisition alone is not enough to guarantee the persistence of biological diversity. Investment in habitat restoration and management is urgently needed on public and private lands across the state. To address this need, MassWildlife and the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs continue to conduct habitat management on state wildlife lands and are committed to working with partners to promote these efforts on conserved lands across the state.

Massachusetts is home to over 600 plants and animals designated as Species of Conservation Need (SGCN). These include rare species like the grasshopper sparrow and bog turtle, which are listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act, as well as more common species such as the ruffed grouse and brook trout, which are vulnerable to threats. MHMGP funding supports restoration of habitats that support a variety of SGCN. Over the past 10 years, the program has awarded over $3.5M in funding to 43 different organizations and individuals for 118 habitat improvement projects.

Grant applications will be accepted starting September 26, 2025 and are due by October 31, 2025. Visit MassWildlife's Habitat Management Grant Program web page to learn more about the application process and to see examples of funded projects.