Introduction

This attractive vegetated buffer helps keep lawn contaminants, such as herbicides and fertilizers, from entering coastal waters.

Vegetated buffers are areas with a dense growth of shrubs, trees, high grasses, perennials, and other plants that have been strategically located to help slow, capture, and filter stormwater runoff. Through this process, vegetated buffers remove nutrients, sediments, chemicals, and other pollutants that can otherwise flow to waterbodies and pose health risks to people and wildlife. By helping stormwater to infiltrate (i.e., filter into the ground), vegetated buffers can also improve groundwater supplies and reduce flooding and drainage problems. In addition, the plants help prevent erosion by shielding the ground from rainfall and stabilizing soils with their roots. The benefits of vegetated buffers can be maximized by using native plants, which are adapted to local conditions and typically require less water, fertilizer, and pesticide than lawn or non-native plants. Using native plants also helps create wildlife corridors and nesting sites, while attracting pollinators such as bees, butterflies, and birds. A vegetated buffer is a relatively easy, effective, and low-cost option for reducing stormwater impacts.

Replacing lawn with vegetated buffers provides significant stormwater management benefits. Vegetated buffers absorb and filter stormwater much more effectively than lawn, and they do not require fertilizers and pesticides that contribute to runoff contamination. Once established, vegetated buffers also require little maintenance compared to lawns, saving time, water, and money spent on lawn-care products. Finally, unlike lawns, planting a mix of native grasses, perennials, shrubs, or trees can provide year-round color and interest, help frame a shoreline view, create a privacy screen, direct and limit foot traffic, and offer habitat for wildlife.

Impacts to Neighboring Properties - Stormwater management practices must be designed to responsibly manage runoff from your property without transferring problems to neighboring properties, roads, and municipal drainage systems. Planting projects that include soil excavation could cause “muddy” water to run off your property during storms. Similarly, re-grading activities could improperly redirect water and cause flooding problems in roadways or neighboring yards, basements, or leach fields (potentially causing a septic system failure). During land alteration activities, be sure that erosion and sediment controls are in place to capture stormwater onsite. Carefully following the design guidelines in the Stormwater Solutions for Homeowners fact sheets will help you avoid impacts to neighboring properties. If in doubt about offsite impacts, consult a professional, such as a civil engineer or landscape architect.

Photo credit: George Headley, Mass.gov Images

For properties near beaches, coastal banks, dunes, floodplains, rivers, salt marshes, wetlands, and other “resource areas” protected under the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act,* vegetated buffers can be particularly beneficial for reducing stormwater impacts. Projects that cause alterations near or within these resource areas, however, are likely to require a permit through the local Conservation Commission. To maximize benefits and avoid impacts to resource areas and adjacent properties, permitted projects must be properly designed, installed, and maintained. For example, short-term construction impacts must be minimized by providing erosion and sediment controls. Where work is within the 100-foot buffer zone (i.e., adjacent to but outside of any resource area), minor landscaping activities such as the planting of native trees, shrubs, or groundcover (excluding turf lawns) will not likely require a permit if the work is minimal and will not cause excessive land disturbance. Homeowners are encouraged to contact their local Conservation Commission before undertaking any work to determine whether a resource area exists, what permitting requirements may apply, and how to avoid impacts. In addition, for additional requirements for planting or restoration activities in threatened or endangered species habitat, such as in or near coastal dunes, contact the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

*MGL Chapter 131, Section 40 and corresponding regulations at 310 CMR 10.00.

Location for a Vegetated Buffer

These tips for selecting a location can help maximize the effectiveness of vegetated buffers.

Stormwater from this roof is directed by a downspout to the densely planted vegetated buffer along the driveway, which helps to infiltrate the water and filter pollutants before reaching the road. The plantings also provide privacy and great “curb appeal.”

- Directly capture stormwater - Vegetated buffers best capture stormwater and filter pollutants when they are placed along the border of waterbodies or adjacent to impervious areas such as driveways, patios, rooftops, and other surfaces that do not absorb water. Where necessary, install or redirect downspouts or regrade the ground surface to redirect the flow of water to the vegetated buffer—but be sure to distribute the water over a large area to avoid concentrating the runoff, which can wash out plants and soils. (Also be sure that regrading does not convey water onto neighboring properties or into roadways.) Placing crushed stone uphill of the vegetated buffer can help disperse and infiltrate some of the flow before it reaches the buffer.

This strip of plants can more efficiently capture runoff than the lawn, helping to keep stormwater from flowing to the road and storm drains.

- Replace existing lawn - Lawns (which are typically mowed short and have a shallower root structure) tend to become compacted, making it difficult for water to infiltrate. Trees, shrubs, perennials, and long grasses have deeper roots that create pathways for water to enter the ground and be absorbed by the plants. These plants can also thrive with less fertilizer and water than lawn grasses. Therefore, replacing lawn with a vegetated buffer can substantially reduce stormwater impacts.

- Avoid steep slopes - A vegetated buffer may not be able to fully manage the concentrated flows or volumes of runoff on steeper slopes (i.e., areas with a grade greater than 5 percent). If you cannot avoid steep slopes, you may be able to compensate by adding crushed stone on the uphill side of the buffer to help slow and infiltrate the water and/or by using particularly hardy, erosion-resistant plants, such as big bluestem (Andropogen gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica), and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum). Another option is to break up the slope into terraces (i.e., multiple flat areas, or steps) and plant them with vegetation. These planted terraces can help intercept cascading water, minimizing the potential for erosion and providing a level area for water to infiltrate (see the illustration in the Installation section for an example).

Size and Shape of a Vegetated Buffer

While a vegetated buffer of any size can be beneficial on your property, these guidelines help to optimize buffer width and length.

With just a few rows of small plants, this vegetated buffer helps absorb stormwater and filter pollutants from driveway runoff.

- Buffer width - All buffers slow, capture, and filter stormwater runoff and therefore offer significant advantages over lawn or impervious surfaces. However, the buffer width needed to fully treat stormwater depends on many factors, including the size of the drainage area, slope of the land, soil infiltration rates, pollutant levels in the runoff, and type and amount of vegetation planted. Most sediments and pollutants are filtered out within the first 10 feet of a buffer in well-drained, flat areas—but wider buffers are needed to fully treat runoff with higher pollutant levels (such as road runoff) and in areas with steeper slopes or soils that do not drain well. As a general rule, buffers should be at least 30 feet wide to provide reliable stormwater treatment near wetland resource areas. To serve as wildlife corridors, buffers should typically be even wider than those designed for water quality protection.

- Buffer length - A continuous buffer is better for capturing runoff, filtering and infiltrating stormwater, and providing wildlife habitat than a fragmented one. Placing the buffer along the entire length of a driveway or other impervious surface maximizes its capacity to capture and treat stormwater runoff. In addition, installing a continuous buffer along the edge of the waterbody to be protected maximizes the capture and treatment of contaminants. If you need to design an accessway through the vegetated buffer, create a winding pathway to avoid channeling fast-flowing water.

Planting Methods

Choose one or combine both of these methods to create a dense and healthy growth of plants.

This streamside vegetated buffer of wildflowers and grasses helps filter out nutrients and chemicals before they reach the water. If planting a vegetated buffer along a waterway or other wetland area, be sure to follow the guidelines in the “Do You Need a Permit?” section before undertaking any work.

- Let it grow - The simplest way to create a vegetated buffer is to just allow existing plants to grow. When a lawn is no longer mowed, it will undergo a natural succession from lawn grasses to a greater variety of wild grasses and wildflowers, eventually transitioning to woody shrubs and trees. You can enhance the process by seeding with a native wildflower mix or planting a few native shrubs that can spread or reseed. To help seedlings to become established, lawn may need to be removed or smothered before planting (see the “remove or smother grass” bullet in the Installation section). Be sure to watch for invasive species, such as bittersweet and honeysuckle, which have the potential to turn your buffer into a thicket of undesirable species. See StormSmart Properties Fact Sheet 3: Planting Vegetation to Reduce Erosion and Storm Damage for more information about removing invasive species on or near coastal banks or the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program’s Invasive Plants website for additional resources on identification and management.

These thriving grasses, perennials, and woody shrubs were allowed to grow out and now provide a beautiful buffer to the salt marsh and sea.

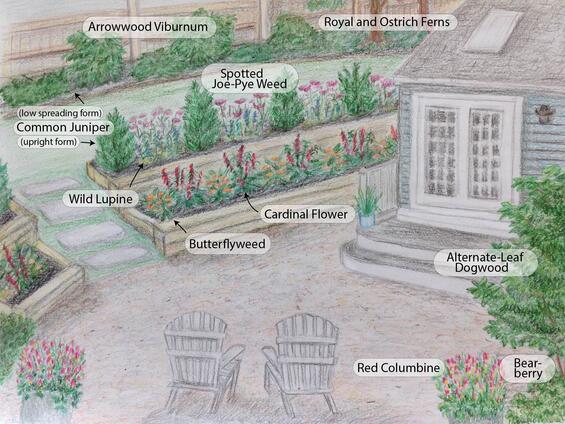

- Plant the area - When choosing species to plant, select a variety of hardy natives. On the coast, salt-tolerant grasses with extensive root systems can quickly and effectively stabilize large areas and require little maintenance to grow. Shrubs and trees can be planted for numerous benefits, including their ability to capture and use significant amounts of stormwater, provide habitat, and shade and maintain water temperatures for streams, rivers, lakes, and ponds. Trees and shrubs are also good choices for capturing pollutants and filtering sediments from parking areas and driveways since they are less likely to get smothered by sediments. (They also offer an excellent screen to provide privacy in your yard.) Increasing the variety of grasses, perennials, shrubs, and trees that provide year-round cover allows more opportunity to slow water and absorb nutrients in all seasons (compared to mown lawns that are even less capable of reducing stormwater flows in the winter than in the growing season). To maximize effectiveness, your vegetated buffer should eventually form a thick, dense cover that can withstand strong water flows, any flooding that occurs, and occasional dry periods. For ideas, see the following illustration of a landscape plan showing native plants installed along a coastal bank, as well as the plant list in the Native Plants for Vegetated Buffers section and the illustration of the landscape plan of a terraced garden in the Installation section

This landscape plan shows a vegetated buffer along the top of a coastal bank with hardy, salt-tolerant native species, including an Eastern red cedar tree, bayberry, beach plum, and common juniper shrubs, asters as colorful perennial wildflowers, and bearberry, sweet fern, little bluestem, purple lovegrass, and switchgrass as various forms of groundcovers. Projects on coastal banks and in or adjacent to other “resource areas” under the Wetlands Protection Act require a permit, so be sure to contact your local Conservation Commission before starting work.

Installation

Prepare the area and select the appropriate species for a vegetated buffer using these guidelines.

- Remove or smother grass - When planting in existing lawn areas, removing the established turf can help new plants (especially grasses and perennials) get established. One option is to manually dig up and/or till the grass with a sod cutter, rototiller, or shovel. Though labor intensive, manual removal creates an open area that can be planted right away. When soil is exposed, be sure to use measures to prevent erosion (see Stormwater Solutions for Homeowners Fact Sheet: Preventing Erosion). Another option to remove existing grass is to smother the lawn with cardboard or newspaper (the high temperatures and lack of light will eventually kill the grass). The dead grass can be left in place and planted with potted plants or plugs and/or seeded with a native mix. This method requires sufficient time to kill the grass before the vegetated buffer can be planted, but overall, it takes less effort, reduces erosion problems, and helps keep invasive plants or weeds from taking over.

- Amend the soils - While plants that thrive in the existing soils should be selected for the vegetated buffer, you can help promote plant growth by adding compost, particularly if soils are compacted or deficient in organic matter. Compost adds nutrients for plants, helps the soil retain water and air, and provides an environment for beneficial soil organisms. For bare soil, mix the compost in before planting. For areas with existing vegetation (such as lawns growing out or smothered grass left in place), add a layer of 1-3 inches of compost and rake and water it in. The compost will eventually break down and settle into the ground as the vegetation grows through. Compost can be added to the vegetated buffer every few years to maintain soil health.

- Select and install plants -The Native Plants for Vegetated Buffers section lists plants native to Massachusetts that are appropriate for vegetated buffers in both coastal and inland conditions (for a more comprehensive list of coastal plants, see CZM’s Coastal Landscaping website). Select plants based on the site’s soils, exposure to wind and salt spray, and sun exposure. Plant each species at the appropriate time of year (generally spring or fall when more moisture is available) and follow the specific planting and care instructions provided on the plant label or seed packet. (When seeding on exposed areas, use more seed than recommended on the packet to help ensure that the seedlings will outcompete weeds and invasive species.) Choose plants with a variety of textures, colors, heights, blooms, and fruits for added interest in your vegetated buffer (see the landscape plan showing a terraced garden in this section for examples).

- Only use live plants - With the exception of mulch and leaf litter, do not place dead plant material—such as brush, discarded Christmas trees, and large piles of lawn clippings—within the vegetated buffer. This material limits the natural growth and establishment of plants and root systems and can increase erosion. Therefore, use only live plants to effectively bind soils, stabilize the landform, and control stormwater.

This landscape plan shows terraced garden beds built to capture water flowing off the hillside. The beds are planted with native plants, including butterfly weed, cardinal flower, common juniper, spotted joe-pye weed, and wild lupine, while the property is buffered by a thick growth of native shrubs and groundcovers, including alternate-leaf dogwood, arrowwood viburnum, and bearberry, along with a variety of ferns. Red columbine in pots on the patio provide additional color and benefits to wildlife. These vegetated buffers—along with the patio made of pervious pea stone rather than concrete—significantly reduce the flow of stormwater that would otherwise run off the site.

Native Plants for Vegetated Buffers in Massachusetts

The native plants listed in the following tables are good choices for vegetated buffers. The plants are categorized by their suitability for coastal or inland areas (note: most coastal plants are also appropriate for inland areas). Plant names with links connect to descriptions and photographs on Coastal Landscaping Plant Highlights pages.

Grasses and Perennials

| Coastal | Inland (in addition to coastal species) |

|---|---|

| Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) | Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) |

| Eastern Showy Aster (Eurybia spectabilis) | Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis) |

| Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) | Green-Headed Coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata) |

| Pennsylvania Sedge (Carex pensylvanica) | Maidenhair Fern (Adiantum pedatum) |

| Purple Lovegrass (Eragrostis spectabalis) | New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) |

| Red Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) | Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) |

| Seaside Goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens) | Partridgeberry (Mitchella repens) |

| Sweet Goldenrod (Solidago odora) | Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis) |

| Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) | Spotted Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium maculatum) |

| Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) | White Turtlehead (Chelone glabra) |

| Yellow Plume Grass (Sorghastrum nutans) | Wild Lupine (Lupinus perennis) |

Shrubs, Groundcovers, and Trees

| Coastal | Inland (in addition to coastal species) |

|---|---|

| Arrowwood Viburnum (Viburnum dentatum)* | Alternate-Leaf Dogwood (Swida alternifolia) |

| Bayberry (Morella caroliniensis) | American Basswood (Tilia Americana) |

| Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) | Black/Cherry/Sweet Birch (Betula lenta) |

| Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) | Black Huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) |

| Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) | Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) |

| Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) | Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) |

| Black Tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) | Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) |

| Common Juniper (Juniperus communis) | Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) |

| Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) | Flowering Dogwood (Benthamidia florida) |

| Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) | Fothergilla (Fothergilla major) |

| Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) | Gray Dogwood (Swida racemosa) |

| Red Maple (Acer rubrum) | Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum opulus)* |

| Shadblow Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) | Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) |

| Sweet Fern (Comptonia peregrina) | Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago)* |

| Sweet Pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia) | Pink Azalea (Rhododendron periclymenoides) |

| Virginia Rose (Rosa virginiana) | Red Oak (Quercus rubra) |

| White Oak (Quercus alba) | Scarlet Oak (Quercus coccinea) |

| Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) | Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum) |

| Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) |

*The Viburnum Leaf Beetle (Pyrrhalta virburni), which feeds on the foliage of many viburnums and can end up doing extensive damage, has been found in multiple counties of Massachusetts. Be sure to check the most recent status on the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources Viburnum Leaf Beetle page before planting vulnerable viburnum species.

Eastern red cedar (left), sweet fern (middle), and switchgrass (right) work well for coastal (as well as inland) buffers.

Flowering dogwood (left), nannyberry (middle), and mountain laurel (right) make excellent choices for inland vegetated buffers. (Photo credits: flowering dogwood and nannyberry from Pixnio, mountain laurel from Wikimedia Commons)

Establishment and Management

Follow these guidelines to ensure the success of plants and the effectiveness of the vegetated buffer.

- Cover newly planted areas with leaf litter or mulch - For newly planted vegetated buffers, cover the ground surface with 2-3 inches of leaf litter (decaying leaves left in place or mowed and shredded) or organic bark mulch (a finer mulch, such as triple shredded bark, is recommended for its ability to stay in place). Leaf litter and bark mulch help retain soil moisture, lower soil temperatures around plant roots, prevent erosion, and reduce weed growth. Leaf litter offers the additional advantage of providing habitat for beneficial insects and requiring less maintenance (no need for a fall leaf pickup or spring mulch application). Once plants become established as a dense cover, there will be no need for mulching—the “living mulch” of thickly established plants retains moisture, prevents erosion, and suppresses weed growth better than standard mulch, and the connectivity of plantings creates a more natural ecological community that benefits the plants and wildlife.

- Water - Unlike lawns, native plantings typically do not require watering once they become established. Newly planted vegetation, however, needs careful watering until the limited root system can effectively find and absorb water from the surrounding soils, particularly when planted in the hot, dry summer months. To ensure plant survival, follow the specific watering instructions on plant labels and seed packets. Adjust water levels if necessary for weather, time of year, and site conditions, such as soil type and sun and wind exposure (i.e., windblown areas, sandier soils, and dry, hot weather will warrant extra water). When watering larger perennials, shrubs, and trees, place an open hose (with a slow flow), a soaker hose, or drip tubing at the base of each plant to allow water to slowly seep into soils without creating runoff or wasting water. Temporary irrigation systems, such as portable sprinkler heads, are good for providing aerial spray to large areas of plugs and seeds. An irrigation timer can also be used to water at desired times (often early morning to prevent evaporation in the heat of the day). You can water less each year, with only minimal watering needed in the third year, if at all. During long periods of drought, the vegetated buffer will require watering. Use water that has been collected and stored in rain barrels to maximize your conservation efforts (see Stormwater Solutions for Homeowners Fact Sheet: “Green” Lawn and Garden Practices to find out how). For detailed information on watering methods, such as drip irrigation, sprinklers, and hand watering, see the Ashton Real Estate Group’s Smart Landscaping: A Guide to Water-Efficient Irrigation.

- Avoid overwatering - While watering deeply is needed to encourage root growth, overwatering can cause numerous problems, including leaching of soil nutrients, die-off of beneficial microorganisms, soil saturation (which prevents effective stormwater infiltration), and waterlogging of plants (leaving them susceptible to root rot). Plants that are watered less frequently tend to grow deeper roots and become more conditioned to drought. To determine if you are watering too much, dig a small hole and make a ball out of a handful of soil. If the ball holds its shape, feels squishy, sticks to or stains your fingers, or has a rotten odor, the soil should not be watered for a few days. If the soil does not sufficiently dry in that time, you may need to add sand or other soil amendments to help the soil drain and compost to help replenish nutrients and beneficial microorganisms.

- Weed - Weed newly planted buffers regularly to help the plants grow successfully and out-compete invasive species, other undesirable plants, and encroaching lawn grass. Once plants become established, you can weed less frequently.

- Prune and cut - Only minimal pruning and cutting, such as removing dead or diseased limbs, is needed to keep established buffers in proportion and healthy. Avoid cutting or deadheading spent perennials in the fall so that they can continue to provide a seed source for birds and habitat for beneficial insects over the winter. To maintain grassed vegetated buffers or meadows, mow the area once every 1-2 years to prevent the growth of woody plants. (Mow in late winter/very early spring to minimize impacts to wildlife and the growing plants.)

- Greenscape - Avoid using chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides and choose organic methods where possible (see Greenscapes.org for more information). Plants in vegetated buffers will obtain nutrients from natural sources, such as fallen plant leaves, compost, and mulch, as well as from any phosphorus and nitrogen that may be in stormwater runoff.

- Prevent erosion - Inspect the area where water enters and exits the vegetated buffer after heavy rainfall for signs of erosion or plant loss. It may be useful to install an erosion-control blanket made of natural fibers to stabilize soils until plants become established (for details, see CZM’s StormSmart Fact Sheet 5: Bioengineering - Natural Fiber Blankets on Coastal Banks). Placing crushed stone uphill of the vegetated buffer can help slow stormwater flow to the area and reduce soil erosion.

This buffer was planted with shrubs, grasses, and flowering perennials, including Virginia rose, winterberry, bayberry, switchgrass, little bluestem, boneset, butterfly milkweed, swamp milkweed, and blue vervain, to help intercept stormwater that flows off the lawn (and the fertilizers and other contaminants it may carry). While functioning to protect the salt marsh, this buffer also provides a wealth of habitat and food resources for birds, butterflies, and other pollinators.

Additional Information

- For related fact sheets, see the CZM Stormwater Solutions for Homeowners fact sheet website.

- The CZM Coastal Landscaping website has details on landscaping coastal areas with salt-tolerant vegetation to reduce storm damage and erosion.

- Also from CZM, StormSmart Properties Fact Sheet 3: Planting Vegetation to Reduce Erosion and Storm Damage gives specific information for homeowners on appropriate plants for erosion control in coastal areas.

- CZM’s CZ-Tip - Keep Waterways Clean by Filtering Pollutants with Plants discusses reducing runoff impacts by planting vegetated buffers.

- The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) Massachusetts Clean Water Toolkit provides guidance on nonpoint source pollution prevention and provides links to many fact sheets, including Tree and Shrub Planting.

- MassDEP’s Massachusetts Buffer Manual: Using Vegetated Buffers to Protect Our Lakes and Rivers (PDF, 2.4 MB) includes information on the benefits of vegetated buffers and how to design them.

- MassDEP’s Lawns and Landscapes in Your Watershed offers tips and resources for planting natural pollution barriers, selecting alternatives to lawn grass, and reducing fertilizer, pesticide, and water use.

- The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP) maintains information on protected animal and plant species in Massachusetts, along with Priority Habitat and Estimated Habitat Maps to help determine if a proposed project is in or near habitat for animal species listed as endangered, threatened, or special concern.

- The Ecological Landscape Alliance website, which includes links to their newsletter, conferences, and webinars, offers design ideas and tips from professionals that install buffer plantings and other ecological landscapes.

- The Greenscapes website provides information on “green” lawn and gardening practices and includes a downloadable Greenscapes Guide that details information on how to use attractive, nature-friendly landscaping practices to reduce pollution, conserve water, support wildlife, and protect against climate change.

- The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) GreenScaping: The Easy Way to a Greener, Healthier Yard provides guidance on maintaining an environmentally friendly landscape by building healthy soils, choosing the right plants, conserving water, and using pesticides wisely.

- EPA’s National Menu of Best Management Practices for Stormwater has fact sheets on berms, regrading, swales, and other stormwater control practices.

Other Available Stormwater Solutions Fact Sheets

Fact sheets are currently available on these techniques:

- “Green” Lawn and Garden Practices - Environmentally friendly yard care methods—such as planting native species, conserving water, and reducing fertilizer and chemical use—help to protect water quality and can save time and money.

- Rain Gardens - Rain gardens are specially designed and planted depressions in the ground that collect, filter, and treat stormwater.

- Vegetated Swales - Vegetated swales are channels with moisture-loving plants and amended soils that intercept, treat, and slowly convey stormwater runoff to where it can be effectively infiltrated.

- Reducing Impervious Surfaces - Impervious surfaces (such as asphalt driveways and concrete patios) allow greater volumes of stormwater to flow quickly offsite, carrying contaminants and causing local flooding and erosion. Replacing impervious surfaces with gravel driveways, planted areas, and other options that infiltrate or absorb water can significantly reduce stormwater problems.

- Minimizing Contaminants - Household contaminants—such as oil from automobiles, toxins from pesticides and cleaning products, and bacteria from pet waste and septic systems—can contribute to stormwater pollution. But simple changes at home, from reducing fertilizer use to properly disposing of batteries and other hazardous household products, can help keep inland and coastal waters clean.

- Preventing Erosion - Stormwater can carry sediments that fill storm drains, obstruct channels, smother wetlands, and cause other water quality and habitat impacts. Erosion and sediment controls can help slow and redirect stormwater, reducing erosion and capturing sediments and attached pollutants on site.